A who's who of conservative celebrities gathered in November in Asheville, N.C., to honor and praise Billy Graham, the famed Christian evangelist, on the occasion of his 95th birthday. Inside the hotel ballroom, Donald Trump and Sarah Palin rubbed elbows with Rupert Murdoch, Glenn Beck, Greta van Susteren and Rick Warren.

"Billy Graham, we need you around another 95 years," Palin said. "We need Billy Graham's message to be heard, I think, today more than ever."

At one of the head tables, right next to Kathie Lee Gifford, sat a 34-year-old rapper who looked out of place among the mostly older, white VIPs. Lecrae Moore had not been raised a Christian, and had not grown up listening to Graham preach. His childhood role models had been rappers like Tupac, and he had spent his teenage years running the streets.

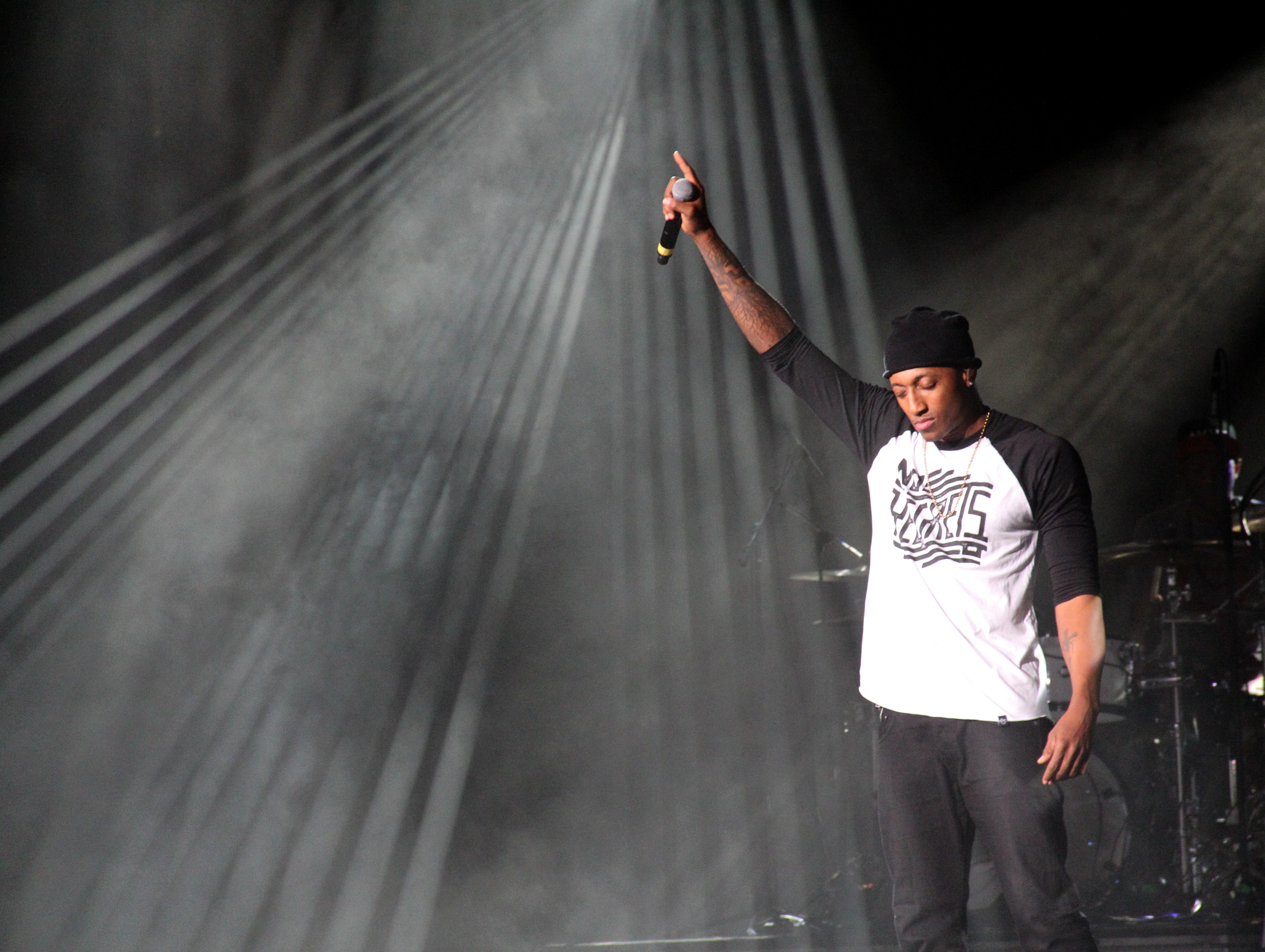

But Lecrae -- who was featured in Graham’s recent “final sermon” video -- has also become an ambassador for Christendom. His delivery is just a bit different.

Over the last several years, Lecrae has become a successful rap artist with a rare message that is explicitly Christian. His 2008 album "Rebel" became the first rap album to hit No. 1 on the Billboard Gospel chart, and his 2012 record "Gravity" won a Grammy for best Gospel album. He has also become a staple of the Christian music festival circuit, headlining concerts in front of thousands of fans.

But over the past two years, Lecrae has been trying to break out of what he calls the "Christian ghetto," to some success. He was part of last year’s Rock the Bells tour with Wu-Tang Clan, Common, Black Hippy and J Cole; has become a regular guest on BET’s “106 & Park” and has recorded songs with artists such as Pete Rock, Big Krit and Chaka Khan. One BET executive compared his first listen to Lecrae to the first time he heard Kanye West.

Lecrae’s attempt to infiltrate popular culture while retaining a clearly Christian message is a difficult task, but he embodies a larger trend inside Western Christianity. Lecrae is one of many modern evangelicals who have rejected the path set by the combative "Moral Majority" culture warriors of the 1980s, and instead embraced an assimilation into the mainstream and its formative institutions, hoping to shape it from within.

Lecrae doesn't want to forsake his beliefs. He wants to take his message with him. But some of Lecrae's fans have already accused him of selling out, because he appears on stage with other rappers who are non-Christians, or records songs with them.

As Lecrae said last summer, a few hours before he took the stage at the Creation Festival, one of the biggest and oldest stops on the Christian music festival circuit, "It's such an uphill battle."

The morning after Graham's birthday bash, Lecrae flew to Las Vegas to attend the Soul Train Awards. "That was completely different worlds," he said.

He has been spending an increasing amount of time in the mainstream hip-hop world. He first burst the Christian bubble in the fall of 2011 when he performed in a freestyle showcase as part of BET's annual awards show -- "Hey, this what happen when hip-hop lets the saints in," he quipped then -- and the network has continued to promote Lecrae heavily.

“I will equate that feeling I got when we identified Kanye West," Kelly Griffin, director of music programming at BET, said of the first time he heard Lecrae. "Like, 'Wow, we want to take a chance on him.’”

In October, Lecrae found himself inside a cramped New York sound booth next to Sway Calloway, the 43-year-old MTV personality, rapper and journalist whose daily radio show, “Sway in the Morning,” is broadcast nationally on SiriusXM.

"We got a hybrid artist here," Calloway told listeners. "Now, even I used to say he's a Christian rapper. But he's a rapper -- who is a Christian."

A quiet grin spread across Lecrae's face. That’s a distinction he likes to make often. The way he explains it is you don't call it Christian architecture, or a Christian pharmacy, or Christian pottery, when it is simply done by a Christian person. Rather, to be a Christian and also be an architect, or pharmacist, or potter, is supposed to mean that an individual performs those professions to the best of their ability, and with passion and excellence.

And as Lecrae points out, hip-hop is full of rappers who practice Islam or incorporate messages of the Five Percent Nation, such as some members of Wu-Tang Clan. They talk about their faith in their rap, but they are not labeled "Muslim rappers."

Yet even as BET hailed him as the next Kanye, Lecrae drew a distinction between himself and the artist better known as "Yeezus."

"I deeply respect what he's doing artistically. I do think there's a lot of brilliance," Lecrae said. "There's a line between being egotistical and being genius or great. And I think he plays with that a lot."

Still, he continued, saying of Kanye's most recent album, "I hear a broken person, if I'm going to be honest, when I listen to it."

"I'd say even the writing, like, from my end, from my perspective it's not as thought-provoking," he said. "It feels a little hasty, a little like, 'Let me just get this off my chest,' versus, 'How do I say this in a unique way?"

Uniqueness is a quality that has largely been lacking in Christian music. The genre didn't really exist until the 1970s, some time after the advent of rock-and-roll. Its creation was the product of a desire among many evangelicals to resist a culture they felt was increasingly non-Christian. But the genre's downfall -- like many of the cultural artifacts that have come out of evangelicalism over the last several decades -- was that instead of creating better alternatives, it just made knockoffs.

John Jeremiah Sullivan captured this in a memorable 2004 piece he wrote for GQ magazine about his own trip to the Creation Festival.

"Every successful crappy secular group has its Christian off-brand, and that's proper, because culturally speaking, it's supposed to serve as a stand-in for, not an alternative to or an improvement on, those very groups. In this it succeeds wonderfully. If you think it profoundly sucks, that's because your priorities are not its priorities; you want to hear something cool and new, it needs to play something proven to please … while praising Jesus Christ. That's Christian rock," Sullivan wrote.

Or as Cartman, of "South Park," put it: "All right guys, this is going to be so easy. All we have to do to make Christian songs is take regular old songs and add Jesus stuff to them. See? All we have to do is cross out words like 'baby' and 'darling' and replace them with, 'Jeeesus.'"

This subculture was created by the belief throughout much of American evangelicalism that all Christians were required to verbally proselytize for their faith as often as possible. Music wasn't good -- or in other words, approved of -- unless it was didactic.

"There's this whole subtle idea behind Christian music that you always have to be telling people about Jesus. It's ludicrous, because no one who isn't a Christian would ever want to listen to that music," David Bazan, a musician who performs under the name Pedro the Lion, told Andrew Beaujon for the 2004 book Body Piercing Saved My Life.

Lecrae’s goal is to deliver a message of faith and hope to a non-believing audience. But a “faith stigma” can prevent that audience from ever hearing him in the first place, he said. So endorsements from influentials like Sway are a big step toward gaining wider acceptance.

Lecrae "makes being a Christian cool," Griffin, the BET director, said. "It doesn't feel preachy. It doesn't come off as holier than thou, but speaks to people's circumstances, experiences, and just life in general, just like regular hip-hop."

For a long time, Lecrae didn't think Christianity was cool himself. He was born in Houston, Texas, to a single mother and moved around a lot as a kid, to Dallas, Denver and San Diego, where he lived with his grandmother. He spent most of his teenage years making mischief.

"They nicknamed me 'Crazy ‘Crae,'" he told Complex magazine in 2012. "I would just do whatever, whenever, however. I’d get drunk, jump out of a third-story balcony. So I just lived reckless. I think I just didn’t really know what I was living for. I was just living for whatever happens today and that was the extent of it for me."

“He was a heavy drinker, party animal, he was a ladies' man,” said Torrance Esmond, an old friend who is now the executive producer at Lecrae's record label, Reach Records. “He used to just do the real silly stuff and you'd be, like, ‘Dude, what are you doing? Why are you driving 125 miles an hour down I-94 on Friday night?’”

Lecrae's conversion to Christianity was gradual. When he was 17, a friend from high school invited him to a Bible study.

"I went, and I had never seen Christians who dressed like me or talked like me, so I thought they were Martians from another planet!" he told an interviewer in 2012. "When I saw them, I said, 'Oh you guys are human!' They loved me genuinely and that’s really what started it."

A year or two later, he attended a Christian conference with friends, and a sermon he heard there resonated deeply with him. He ended up marrying a woman he met at the Bible study, Darragh Moore. They have three children together.

By 2002, he was visiting youth detention centers with a Christian organization. Sometimes he would rap, and he began to see how music could be a way to spread the gospel.

Two years later, Lecrae founded Reach Records with a friend, Ben Washer, and soon after they released "Real Talk," the first of Lecrae's six albums. Over the last two years he has also released two mixtapes, "Church Clothes" and "Church Clothes 2," both of them hosted by DJ Don Cannon, who is now vice president of A&R at Def Jam Recordings.

"I think we've made a lot of room, and people are beginning to see me as my own entity, as kind of my own category," Lecrae said.

Seated inside his tour bus, parked on a rain-soaked field in central Pennsylvania at the Creation Festival last summer, Lecrae admitted that his attempts to break out of the Christian music world were not sitting well with some of his more hard-core fans.

"It's so counter-cultural to all this," Lecrae said of his vision, gesturing past the walls of his bus and toward the scores of muddy teens and youth-group leaders trudging among campsites and up and down Hallelujah Highway.

“Christians have no idea how to deal with art,” Lecrae said more recently, during a September speech to Christian leaders. “They say, 'Hey Lecrae you can't do that. That's bad. That's secular. You can't touch that. Hey Lecrae, your engineer is not a Christian. He can't mix your stuff. He's going to get sinner cooties on it.'”

“This is real. I wish I making this up,” he said.

Lecrae's songs are still centered around a Christian worldview and approach to life, but to some Christians, the outside world is something to be shunned, not engaged.

"So Lecrae modestly mentioned Jesus, yet he passionately bopped his head to extreme negative rap,” one fan wrote on YouTube. “Aren't we as Christians called to be set apart from such profanity; rather than to be taking pride or joy in it?"

"Lecrae is a secular rapper now. … The world got to him. And now he's rapping for the world. … Lecrae, what happened?!" lamented another.

These types of comments populate Lecrae's Instagram feed, his YouTube videos. Fans even criticized Lecrae’s wife for wearing a dress that they thought was too short. It’s enough to make Christianity unappealing to even its most faithful adherents. But this reaction is the product of decades of evangelical thought.

Evangelicals adopted an isolationist mindset for much of the 20th century. Non-Christians, the thinking went, carried sin like a virus, and the point of following Jesus was to remain as pure as possible. Christians established their own communities, educational institutions and music festivals, separate from the rest of the world.

The rise of the religious right, led by Jerry Falwell and the Moral Majority in the 1970s and '80s, represented an acknowledgment by evangelicals that their retreat from culture was not working. America and the West in general were moving so far away from their point of view that they needed to fight back.

"For many Christians cultural engagement simply meant opining on politics … or denouncing a slouching-toward-Gomorrah view of the culture around us," said Russell Moore, the recently installed head of the Southern Baptist Convention's Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission.

The crucial miscalculation made by Falwell and his followers was believing that they had the upper hand, that they outnumbered their culture war opponents. It may have been easy to think that when many Christians lived in conservative states, surrounded by others who thought like them. But in fact, the country was changing -- demographically, ethnically and culturally -- in ways that have now made religious conservatives increasingly a minority. America is a more pluralist, urbanized nation now than ever.

Even during the days when fundamentalist thought dominated evangelicalism, there was a resistant, if minority, strain that insisted there was a different way. Well-known author C.S. Lewis captured it succinctly in a 1945 essay.

"What we want is not more little books about Christianity, but more little books by Christians on other subjects -- with their Christianity latent," Lewis wrote.

There was an aesthetic and moral driver behind this sentiment: If you are an artist, make art, not instructional materials, because that is the right thing to do and that is how you reflect positively on your creator. The same goes for science, or politics.

But Lewis' exhortation was inherently strategic. His point, essentially, was that the best way to influence how people think is not to hit them over the head with your point of view, but rather to shape subtly the things they assume to be true about the world.

Lecrae acknowledged that the question of influence is behind his desire to be known first as a musician, rather than a member of a religion.

"I'm digesting C.S. Lewis and Tim Keller and so on and so forth, Francis Schaeffer," Lecrae said, referencing some of the most influential evangelical thinkers of the last half-century. "I'm seeing how they've affected culture and politics and science and so on and so forth, with implicit faith versus explicit faith."

"And so, what I've just wanted to do is do that, which has been a little more difficult for me because I did start off very explicitly. That's what Christians know me for,” he said. Lecrae’s first albums emphasized spelling out his beliefs more than making the best music possible. “So when I venture outside of that now, it's almost as if I'm punting everything that I believe because I'm not as explicit."

And so it is with modern evangelical Christianity; Almost by necessity, because it is no longer the majority view, evangelicalism has become more sophisticated in its understanding of the way faith interacts with the world outside the walls of church. Yet at the same time, it is still grappling with a loud minority who are the offspring of decades of bifurcated thinking.

“The hard-lined wing of evangelicalism that would criticize someone like Lecrae for ‘selling out’ is a very small piece of the evangelical world these days. If anything, American evangelicalism prizes recognition and engagement in mainstream culture these days,” said D. Michael Lindsay, author of Faith in the Halls of Power, and now the president of Gordon College.

Moore said that evangelicalism has seen a “recovery of a broader Reformed and Lutheran emphasis in evangelicalism on vocation, with artistic gifts seen as potentially God-honoring even if they are not strictly means to ministry or evangelism.”

Lecrae believes that the best way to change popular culture, and ultimately to make a difference in people’s lives, isn't to attack others, but to build trust through personal relationships. In 2007 he moved to Atlanta, the center of the Southern rap world. It was a professional decision, giving him the opportunity to network and build his career. But it has also given him a chance to speak about his faith to influential members of the hip-hop community.

“I live in Atlanta because Ludacris lives in Atlanta,” Lecrae said at the Christian leader conference last fall. “And because T.I. lives in Atlanta, and because Lil Wayne comes to Atlanta to hang out all the time, and because Rick Ross' engineers are in Atlanta. I live in Atlanta because I'm from that world, and I can engage that world, and I can go to these studios, and I can have conversations, and I can wrestle with things back and forth with them.”

“If I was scared that that would somehow jump on me and corrupt what I'm doing, I’m rendered ineffective,” he said. “They would never hear the truths that God has invested in me.”

Lecrae has befriended Kendrick Lamar, who in the past year has become the hottest name in rap.

“I'm on the phone with [him] on a consistent basis just talking through life issues,” Lecrae said at the Creation Festival.

Esmond, Lecrae’s producer, said that in the times he has seen Kendrick and Lecrae hang out, it’s clear that “Lecrae ain't trying to get nothing from Kendrick.”

“He ain't pressing to do no song with him. He ain't trying to go on tour with him … Kendrick recognizes that,” Esmond said. “[Lecrae] is more concerned with being a real friend to Kendrick.”

Lecrae told me in a recent phone call that he looks to Bob Marley, the famous reggae artist, for inspiration.

“We talk about being revolutionary and about Bob Marley and the level of his influence and what that looks like as a musician,” he said. “And it wasn't just done by saying great things over mediocre music. It was done by saying great things over great music.”

Nonetheless, when Lecrae sat in his tour bus at the Creation Festival last summer talking about his critics, it was clear the pressure from both sides had worn him down.

"The most stressful part is coming from the Christian side. Because everybody has a standard and a conviction that they believe you need to be living by," he said.

"On my worst days, on my worst days, I ask myself, 'Am I everything these Christians say I am? Am I the hypocrite, am I falling off? Am I too concerned with all this stuff? Am I even making a difference with this music?'" he said.

"On my best days," he continued, "I'm like, 'I am exactly where I'm supposed to be, and this is exactly what I was built for.'”

Before You Go