When I lost my longstanding full-time writing instructor position at a local college as a result of academic cost-cutting politics in 2011, I wondered if I'd ever find another place to put my passion for teaching to use. I'd heard many writers talk about the meaningful work they did as writing workshop facilitators in the prison system. So I gave it a try.

I volunteered to co-teach an ongoing memoir workshop at a women's correctional center. Attending the mandatory code of conduct and policies training session, for two hours I listened to a prison official enumerate the rules. I was to stay aware of what was called the "manipulative ways" of inmates. I was to be vigilant about boundaries. I was not to wear jeans. I was to leave my jewelry at home and my wallet locked in my car trunk.

On my first day of class, I was guided through a series of doors, which were closed tightly behind me. A guard led me down a hallway that was lined by inmates who stood and stared as we passed. I saw their eyes were absent of light.

I wondered how they perceived me.

The classroom was located at the end of the hall. Inside, my co-teacher (a seasoned volunteer) and I arranged the desks in an inclusive circle. The inmates who'd been attending the workshop for several weeks filtered in and took their seats. At the invitation of my co-teacher, they read their writing assignments aloud. Many described the ways they'd been abused as girls by fathers, uncles, brothers, or, as adults, by partners or husbands. They alluded to the reasons they'd ended up in jail. They discussed what it was like to be physically and emotionally separated from the rest of the world.

As the workshop progressed, I listened but I barely said a word. I was focusing on inhaling and exhaling slowly, as my therapist had taught me to do, to bring myself down from a developing panic attack.

After class, I left the prison quickly. Overwhelmingly disoriented, I drove through a tollbooth on the highway without realizing I had to stop and pay.

I never went back.

*

For a long time, I was ashamed to admit that prison wasn't an environment in which I could teach. I'd wanted to make a difference in the lives of inmates, as so many of the writers I admired did. But being in a prison took me back to a place of my childhood, to a different yet (in my mind) parallel world: the abusive home in which I'd grown up, a place with its own set of rules, where I was emotionally "locked up," where things happened behind closed doors, where my vigilance of "manipulative ways" was so necessary it rewired my nervous system into a constant state of alert.

In the women's prison, hearing the words of inmates, I saw the lost and misguided and unsafely vulnerable parts of my younger self in front of me.

I grew up living one life inside and another life outside my home. I was an overachieving student who became a young adult whom clinicians in the trauma field labeled "high functioning": at 29, when I was first diagnosed with "complex post-traumatic stress disorder," I was a woman with an advanced degree, a full-time job, a decent apartment, a relatively stable though socially isolated life. Other abuse survivors coped by dropping out of school, by developing addictions, by becoming homeless, or by prostituting themselves, ending up in prison. I'd been lucky.

But at 37, I understood that for much of my adult life I'd lived in a mental jail. The bars of my past -- of violence and fear and denial --enclosed my cell. For years, I pretended the abuse of my childhood never happened, though it played out in my life long after the events ended: I experienced difficulty cultivating healthy relationships; I allowed myself to be exploited by "friends" and landlords and bosses; I battled debilitating anxiety and depression. I spent my 30s in therapy, addressing and healing from the effects of my past.

In the women's prison, I felt myself getting pulled back down the rabbit hole, that slippery slope that led to my former world of toxicity and suffering and grief.

I couldn't go back. I could only move forward.

*

A year later, I published an essay in Salon about how the experiences of my childhood had affected my ability to be in intimate relationships as a young adult, and how I'd worked in therapy to finally move beyond such difficulties. A writing workshop facilitator at a women's prison across the country shared my essay with inmates.

Through the facilitator, the inmates sent me notes in response. They shared aspects of their stories, and their changed perspectives in prison. They sent short poems, expressions of gratitude, and sentiments of sisterhood:

When I read your story, it touched me because I can relate to how you felt. I want to thank you for sharing your story for it encouraged me to share mine. Your story brought healing.

Without knowing I'd done so, I'd gone back into the prison -- not with my body, but with my words. And while the inmates wrote of the ways I'd helped them, they were helping me: my essay and their responses were a conduit, a bridge connecting their world and mine. Writing transcended prison walls. The incarcerated women ignited a spark I thought had left my life when I lost my teaching position.

*

Recently, I was discouraged by a series of rejections I'd received on my memoir, a book on submission for publication. Editors expressed skittishness about a mother-daughter estrangement and reconciliation story contextualized within a history of childhood sexual abuse. One editor praised the book and held onto my manuscript for many months before ultimately rejecting it with the suggestion that I rewrite the book as fiction, because nonfiction was "too risky" to sell. I declined the idea. While I was open to removing particular portions or revising structure to make my memoir most accessible to mass audiences, I wasn't willing to turn it into fiction. I'd already published excerpts. Readers knew my story was true.

But like many struggling writers, I was beginning to question my work and my path, and my ability to succeed. With competition sky-high, I needed a book contract in order to secure a full-time teaching position. I'd spent three years writing two books and earning a second MFA and cobbling together a living by working several adjunct professor jobs, using money left behind by my late mother to supplement my income. At 40, an age when most of my peers were leading established lives and careers, I could no longer pay my bills. I was staring down the prospect of having to leave my passion behind in order to make ends meet.

One evening, I arrived home after a long day of multiple job and publishing rejections, physically tired and emotionally drained. I took out my key and unlocked my mailbox. Inside was an envelope from a women's prison, handwritten letters from inmates who'd read an essay I'd published in The Huffington Post, "Leaving My Abusive World," about my journey to leave behind the belief system of the abusive world of my childhood in order to live my life more fully.

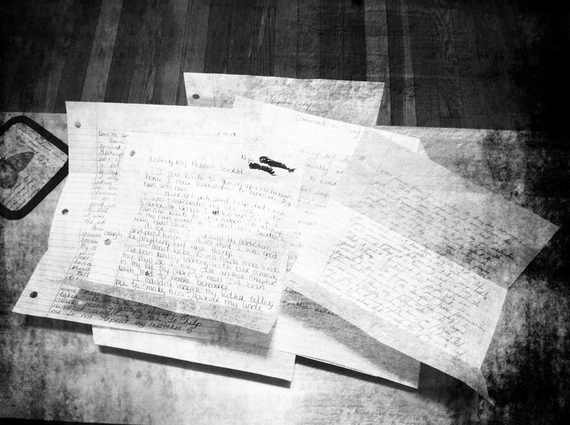

I walked upstairs, entered my apartment, and spread the letters out on my coffee table so that I could see everything. There were words of gratitude and pain and wisdom, words of power and care and courage:

"I love your resolution, to use your tragedies as a ladder to success. I refuse to let my past define who I am now."

The inmates understood that my story wasn't about anything that ought to cause skittishness--it was about the resilience of the human spirit: this was their story. This was our story. This was everybody's story.

This was the love and light of writing, of teaching, of publishing.

As the inmates showed me, through writing we can create community. We can engage people, move them, and help them to feel less alone. We can teach them, through our own example, how to transcend obstacles, to "get free."

"Now here we both are," an inmate concluded. "Things happen, we get stronger."

Tracy Strauss is seeking a publisher for her memoir, Notes on Proper Usage, about her relationship with her late writer-editor mother, the discovery of her mother's secret collection of documents and journals, the abusive man who marked both their lives, and her journey towards forgiveness and reconciliation. Learn more at www.tracystrauss.com.