After 17 months, Sierra Leone continues its fight against Ebola, with five new cases in September alone. The latest is a 16-year-old girl in Bombali district, an area that hasn't had an Ebola case in 169 days. The continued appearance of new cases raises many questions, including how Ebola is spreading and whether or not Ebola will remain endemic in Sierra Leone for the foreseeable future.

To date, there have been over 13,000 cases of Ebola in the country. Ebola has claimed the lives of just under 4,000 Sierra Leoneans, leaving behind bereaved family members, thousands of orphans, and a trauma that lingers in the affected communities. Over 4,000 people have been infected with and survived Ebola, but their challenges have not ended with their recovery.

On my way to Port Loko, one of the districts that was most heavily affected by Ebola, I travelled through communities whose populations were significantly reduced during the darkest days of the virus. In the wake of so much death, the living still wonder how to make life go back to the way it had once been-an impossible task for many, especially those who lost their families' chief breadwinners.

One of the people I met was a woman in her late twenties named Isatu. She was invited to share her story by the local organization Centre for Democracy and Human Rights, which has worked with the Irish aid and development agency, Trócaire, to provide Isatu and many others with psychosocial support and counselling.

Isatu looked like she hadn't slept in days. She stared at me with clouded white eyes, her vision still deteriorated as a result of Ebola nearly a year after her recovery. In some parts of Sierra Leone, vision problems have been found to affect 50 percent of Ebola survivors, and it remains unclear as to how long these difficulties will persist, or if they will ever go away.

Isatu, an Ebola survivor, still struggles with fatigue, deteriorated vision, physical weakness, depression, and mental distress. Photo by Michael Solis.

Isatu, an Ebola survivor, still struggles with fatigue, deteriorated vision, physical weakness, depression, and mental distress. Photo by Michael Solis.

Isatu contracted Ebola from her sister-in-law, who fell ill shortly after attending a funeral ceremony. The sister-in-law's symptoms played out quickly, and before long she was dead. Within a matter of days, Isatu's brother, his baby, and Isatu were all feeling ill with the same symptoms the sister-in-law experienced. The baby didn't survive, but Isatu and her brother did.

The experience was one of the most traumatic of Isatu's life. "There was so much fear," she says. "You didn't know what was happening to you, and nobody had answers. You didn't know if you were going to die, or if you were going to come back."

Readjusting to life after Ebola has not been easy for Isatu, and she was convinced that she had been cursed. Six people in Isatu's family died of Ebola, and her partner ended up leaving her for another woman. Prior to Ebola Isatu had been working as a petty trader, but she still hasn't recovered the strength to carry and sell her goods. For a time she felt like committing suicide and wished that the virus had taken her too, since it had already robbed her of so much.

Serry, a man in his early thirties, is another survivor I met who spoke of his experience with Ebola. He visited the hospital in November 2014 but was wrongly diagnosed with malaria. As the days passed, his prescribed medication proved ineffective and his symptoms worsened. His mother didn't want him to leave for an Ebola treatment center, since Serry, a farmer, was the chief source of their family's survival. If he left for treatment, then that meant he might never come back.

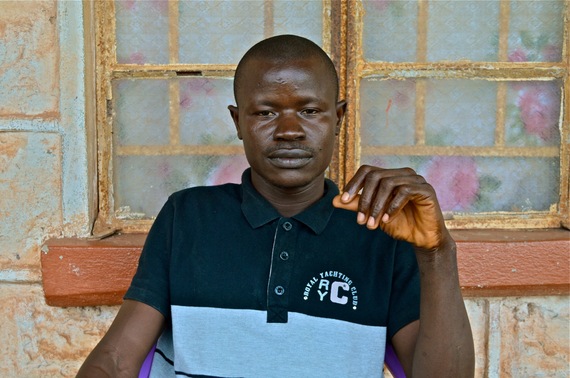

Serry, an Ebola survivor, still struggles with headaches, fatigue, body aches, depression, and mental distress. Photo by Michael Solis.

Serry, an Ebola survivor, still struggles with headaches, fatigue, body aches, depression, and mental distress. Photo by Michael Solis.

"My family cried the day I left," he said. "I didn't want to go on a motorbike or taxi since I might infect someone. So I walked all the way to the treatment center, with body aches and a fever."

After taking another test, Serry found out that he had Ebola. He was quarantined immediately and underwent treatments, remaining isolated for over a month. During that time, he began to feel increasingly guilty about the people he could have infected. He held back tears when he started talking about his wife and 5-year-old daughter, neither of whom visited him while he was in treatment. Taking him for dead and needing to find a way to survive, they left to form a new life. He doesn't know if they are alive or if they too fell victim to Ebola.

Serry's return to his community has been a difficult one. Nearly a year after contracting Ebola, he continues to suffer from body aches, joint pains, and severe headaches. Physically, he is no longer able to do the farm work that he once did, which means he isn't able to bring in money or resources for his family the way he used to do. Having lost his sense of usefulness, he contemplated taking his life, but through counselling he has decided against that.

For both Isatu and Serry, one of the most trying aspects of Ebola has been the stigma they have encountered. Tensions are still high in their communities; in some parts of Sierra Leone communities are in conflict, attributing blame to people who "brought" Ebola to their areas. On the personal level, Isatu and Serry still haven't been able to reassemble the pieces of their broken relationships, a phenomenon affecting many survivors. Field research carried by Dr. Fiona Shanahan of University College Cork confirms the finding that most Ebola survivors report complex relational difficulties and breakdowns, which adds a highly complex layer to their recovery process.

Having experienced a brutal 11-year civil war from 1991 to 2002 that resulted in 70,000 casualties and displaced 2.6 million, Sierra Leoneans know all too well the psychosocial difficulties that result from traumatic experiences. But there was a difference in 2002 as humanitarian efforts were strongly focused on responding to the needs of communities, the displaced, and child soldiers in the war's aftermath. The current government's efforts remain focused on reaching zero Ebola cases, a necessary goal, but this has left a blind spot in responding to the continued needs of survivors and the bereaved.

"Long-term and appropriately resourced psychosocial service provision is required to respond to locally identified needs of people in the recovery process in Sierra Leone," advises Dr. Shanahan. "Without adequate support, follow-up and acknowledgment of the impact of the crisis on people's lives, livelihoods, and long-term wellbeing will be compromised."

Addressing psychosocial needs in the wake of Ebola is important, but it can difficult to do for people who are subsiding on a single meal of rice and oils per day. Ranked 183rd out of 187 countries in the Human Development Index, Sierra Leone remains one of the poorest and most food insecure places in the world, with 72.7% of Sierra Leoneans classified as "multidimensional poor".

Despite these challenges, Trócaire and its local partner organizations remain committed to this second wave of response in Sierra Leone. Much of their work combines livelihoods support to families so they can produce their own food and boost income levels to meet their basic needs, in combination with their participation in psychosocial counselling services.

For impoverished people like Isatu and Serry, who grappled with the decision of whether or not to end it all, the psychosocial support has proven to be lifesaving.

"It's hard to be happy after all of this," Isatu told me just before she hopped on a motorbike for her village. "But I'm taking things one day at a time, small small." Little by little.