It happened the day after nine African Americans were killed during Bible study at Emanuel AME Church. I had spent the day before preparing to moderate the Eli Lilly and Company forum on race. I would spend the hours leading up to the forum in tears for the Charleston 9.

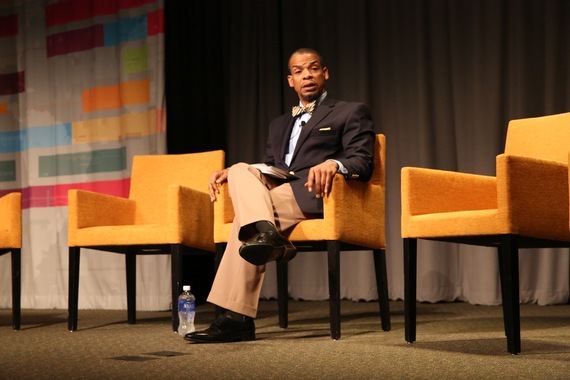

Traumatized by the mass killing and unsure whether I would be able to effectively lead the morning's discussion, I, along with 250 employees from different races and walks of life, convened in a Lilly auditorium for a forum titled, Can We Talk?.

The forum was sponsored by Lilly's African American Network and Global Diversity and Inclusion Office to discuss the effects on Lilly's workforce of racial tensions across America emanating mainly from police-related deaths of unarmed African Americans. It was the first such forum presented by a Fortune 500 company.

I had spent weeks meticulously preparing the forum's questions, scenarios, and panelist briefings. Event day arrived as one of national mourning. It concluded as one of organizational triumph over racism. As an African American diversity professional, I could not have imagined the effects of that forum on Lilly or me in the hours or days prior.

Lilly's chief diversity officer established the context of the discussion. We were there not to litigate the deaths, but rather to talk about how they and other aggressions affected African Americans at work. It was a conversation on the intersectionality of race, society and work that charted new ground for Lilly and, hopefully, the nation.

The panelists were diverse: two African American senior executives and two white members of Lilly's executive committee, the company's highest executive body. The questions were candid. While the panelists had been prepared for a serious conversation, no one really knew where it would lead. Nor had anyone foreseen the esprit de corps that would emerge from an honest and respectful conversation on race in the workplace. We all believed, however, that such a conversation would integrate rather than divide the workforce, providing oxygen for other important discussions.

There was a clear recognition that for African Americans in particular, experiences with racial trauma are difficult to divorce from experiences of work or any other part of life. Further, racial traumas may occur in the normal activities of workplace interactions through inequities, microaggressions and other forms of bias.

A pivotal moment in the discussion came when the panelists addressed how little people of different races truly know each other, even when they spend most of their days together.

A white executive recounted living next door to an African American family in a well-heeled, mostly white, neighborhood. She thought the family was exceptionally quiet -- so much so that her family needed to be quiet too -- until one day the family had a gathering in which torrents of joy and laughter filled the air. She recognized then that her neighbors had been trying to "fit in" with their perceptions of the expected behaviors in their neighborhood. She raised an important question: If the pressure to fit in at home is so great, how much greater is the pressure to fit in at work and what are the implications of that for productivity?

As an example of how unproductive workplace bias can be, an African American executive responded that to combat bias, she spends seventy percent of her time being excellent and the other thirty percent convincing her colleagues of her excellence -- a burden that befalls women and minorities in workplaces across America, but is perhaps doubled in magnitude for African American women.

We discussed a need for management to hold itself accountable for fairness, for investing in employee success, and for creating environments in which everyone excels. Rather than a nice slogan, "inclusion" at Lilly must be a lived reality for all, to which all are accountable.

What happened that day at Lilly is reverberating throughout the company, with executives redoubling their efforts and employees gaining an ability to bring their authentic selves to the workplace.

What can we learn from the Lilly forum?

1. The effects of race in society extend to the everyday work lives of employees.

2. Structured conversations about race can be highly productive in voicing employees' concerns, informing management perspectives, raising the bar for inclusion, and building camaraderie.

3. Employees want to have such forums to grapple with difficult conversations in useful ways.

4. The path to workforce engagement is neither top-down nor bottom-up, but lies instead at the intersection of the two, where a collective consciousness can form.

I learned that the desire for African American inclusion is so great that even in our deepest angst and sorrow in the face of racism, a corporation can have a discussion about the impacts of race on work that lifts spirits and opens new spaces for inclusion to thrive.

The Lilly forum succeeded in narrowing the divide between life and work, black and white, silence and innovation. It should be a model for companies everywhere.