When LinkedIn decided to create a China-hosted version of its website in February, 2014, it made a decision to compromise the company's values in the pursuit of the dollar.

It's important to note that before LinkedIn launched LingYing (the local version of the site), LinkedIn was already active in China. By their own account, they had four million registered users (with little marketing effort), a Chinese-language interface and China-based clients who were buying recruitment ads on the platform (the major source of their revenue). The site had been blocked by the authorities for one 24-hour period but otherwise was always accessible.

So why was it necessary for LinkedIn to create a local entity in China? With a local entity the company would be able to issue official receipts in RMB, making it more convenient for local companies to buy advertising on the site. A local entity also makes it easier to secure marketing deals to promote LingYing in China.

But perhaps the biggest appeal in creating a local entity for LinkedIn is that it would be among the few foreign internet companies who could cosy up with Lu Wei and the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC). Having that kind of a relationship with CAC surely helps the business and those who are associated with the company.

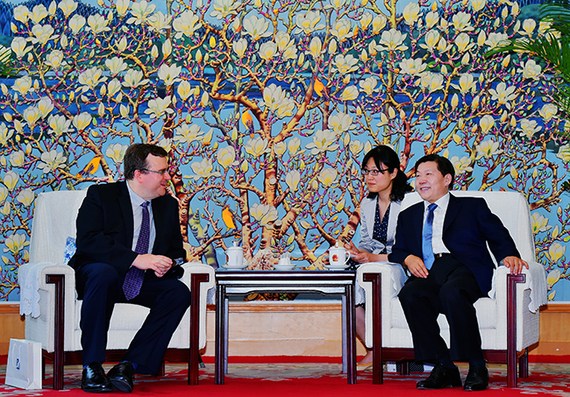

LinkedIn's Reid Hoffman meets China's cyber czar Lu Wei for the umpteenth time.

There are surely other additional benefits, but in order to operate as a local entity, LinkedIn had to agree to the following:

- To censor content and users on the platform, inside and outside of China, on a 24/7 basis at the behest of the authorities.

- To store all data about its Chinese users on servers inside China and to agree to allow the Chinese authorities to access this data whenever they want to.

- To follow all present and future regulations on internet operations in China.

LinkedIn already has egg on its face over its handling of censorship in China. While their commitment to transparency remains vague and noncommittal ("may", "could", "attempt"), the company's CEO, Jeff Weiner, has been more explicit in his description of how he handles censorship. The following is a transcript from the 22 minute mark in an interview with BuzzFeed's Mat Honan:

Weiner: "I'll tell ya, you can have any discussion you want theoretically, but when you are actually asked to censor even one thing, one profile or one update, it's gut-wrenching. It's gut-wrenching. And so we take that very, very seriously.".

Honan: "Do you get involved in those discussions personally?"

Weiner: "So our head of China reports directly to me."

Honan: "Is that a "yes"?

Weiner: "Yeah."

(If you want to listen to the entire China discussion, this starts around the 19 minute mark.)

There is no need to sugarcoat Weiner's disingenuousness in this interview. Anybody remotely familiar with how censorship works in China would be able to tell you that it is near impossible that Weiner personally discusses whether to censor individual updates and profiles on LinkedIn. Nor, for that matter, would his China CEO have the time to do that.

If we want to give Weiner the benefit of the doubt and take his comments at face value, this means that he would have to consider, on a daily basis, all of the censorship directives handed down by the authorities and whether or not they applied to each individual member, plus any requests that have been submitted directly to LinkedIn.

Locally registered internet companies, like LingYing, must censor the information which appears on their sites and employ roughly one censor for every 100,000 users on its platform. In its heyday, Weibo employed 4000 censors in house. With LinkedIn's 9 million members in China, this would mean that Weiner and China CEO Derek Shen are personally handling the work of 90 censors. If true, shareholders should be concerned that the CEO is spending more time dealing with censorship than trying to drive recruitment advertising revenue.

Weiner then goes on to say that the justification for censoring content on a global basis is that the potential exists for content to get "re-circulated" back into China, which may put their "members" in danger. This is an argument that seems to hold weight with many foreign internet firms - that Chinese internet users are not mature enough to understand what is appropriate to post and what is not appropriate to post.

We would posit that perhaps LinkedIn executives are not mature enough to handle China. In the midst of market turmoil, we have seen increased censorship of posts related to how the authorities handle this situation. Surely, this is the type of content that business people in China would be sharing on LinkedIn. Is this the type of censorship that Weiner finds "gut-wrenching"? Has he ever said "no" to the censors?

We likely will not be able to verify that information because of LinkedIn's local entity in China. It appears that this entity does not submit information for LinkedIn's transparency report. China is not mentioned in any report, despite a flurry of update and profile deletions around the two most recent Tiananmen anniversaries. While LinkedIn does not seemingly provide statistics on content removal, it does provide member data to governments upon request. However, no such requests from China appear in the report. What is the point of issuing an opaque transparency report?

This may be due to the fact that the Chinese authorities have requested that LinkedIn not share information about their requests - another pitfall of doing business in China. As China works through the details of its cybersecurity law, who knows what new requests lurk around the corner? What we do know is this - whatever the request, LinkedIn will be there to meet it, because relationships matter.

The issue of storing data in China raises many questions. What constitutes a Chinese user for LinkedIn? Presumably, the 4 million Chinese users who had joined before LinkedIn registered a local entity had their data shifted to China. Were they informed of this change?

When considering LinkedIn's transparency policy on content removal, it is also safe to assume that if you claim to be based in China or if you use the Chinese-language interface, regardless of where you may live or what language you speak, your information will be stored in data centers in China.

This is a dangerous development for many of LinkedIn's users, including dissidents, activists, journalists and those working in the non-profit sector. In 2004, Yahoo infamously handed over the emails of a dissident at the request of the Chinese authorities. These emails were later used as justification for sending the dissident to prison for eight years. By the letter of the law, LinkedIn would need to do the same. This information could include a user's location, communications and the profiles of people that are in their networks on LinkedIn, regardless of whether or not those users are based in China.

Sometime in May 2015, LinkedIn deleted my profile on their website. In all honesty, my profile was likely violating several items in the company's user agreement, including the use of a real name ("Charlie Smith" is a pseudonym). But how the company has handled the censorship of my account and the censorship of news which the Chinese authorities have deemed harmful, raises many questions about how foreign internet firms who wish to operate in the China market balance local laws against freedom of speech.

GreatFire has used LinkedIn since 2011. To the company's credit, LinkedIn helped us find contacts that could help with our mission of ending online censorship in China. We then started to automatically post our FreeWeibo Twitter feed to our LinkedIn profile and we expanded our network by connecting to Chinese who were working in media in China. As the LinkedIn site is not blocked, this proved to be an effective means of distributing banned content.

LinkedIn never informed me my account was taken offline. IFTTT, the app I used to auto post from my Twitter feed informed me that the LinkedIn recipe was no longer working. I wrote to LinkedIn twice before I received an answer about my account. The company then asked me to send government issued-ID to prove that the photo I was using on my profile matched my identity (I used a picture of Lu Wei as my profile photo). After I submitted copies of this information (not my real identity) I was then told that my account was being restricted because of "inappropriate content". They furthermore responded:

LinkedIn determined that recent public activity you posted (such as comments, or items shared with your network) contained content prohibited in China.

LinkedIn users in China who are activists, human rights defenders, working for nonprofits, journalists and the many, many others who operate in fields deemed "sensitive" by the authorities (including lawyers), should take the necessary actions to protect their personal security. The mishandling of the deletion of our four-year old account (with thousands of connections), raises several red flags:

- After submitting my photo identification to LinkedIn for verification, they confirmed that they have deleted this information from their database. But according to Chinese law, this information needs to be retained, even if accounts are deleted.

- After LinkedIn communicated that I needed to submit identification to get my account restored, they then told me that my account would be deleted because content I shared on the platform was illegal (they refused to elaborate on what content, specifically). Confusingly, if LinkedIn was deleting my account over content issues, why was it necessary for me to send them my personal identification?

- LinkedIn will not inform you that your account has been removed or that your updates have been deleted. And their non-committal "commitment" to transparency allows them to take these types of actions.

- If LinkedIn considered my account to be outside of China, then they would likely be able to delete my personal information from their database. But this then shows that they are practicing Chinese censorship on a global basis. If LinkedIn considered my account to be inside China, and they have deleted my personal information from their database, then they are in violation of Chinese law. But because relationships matter, they likely escaped punishment by the authorities.

As China drafts its cybersecurity law, we can thank businesses like LinkedIn for any new, overbearing requirements. LinkedIn have shown that they will do anything for the authorities in return for market access. Now, when a new foreign company wants to enter the China market, the authorities can simply point at LinkedIn and say "these are the minimum requirements you have to meet".

If LinkedIn mimicked their China approach in the West, human rights organizations would be all over them. It is highly likely that the authorities are demanding that LinkedIn hand over sensitive information about dissidents, activists, civil society actors and any other group deemed to be "picking quarrels". By the letter of the law, LinkedIn will have to comply with these requests - but they will simply see this as a "gut-wrenching" cost of doing business and nothing else.

LinkedIn would do well to heed the words of Tom Lantos who, while investigating Yahoo's complicit cooperation with the Chinese authorities, had this to say about American companies operating in China:

Chinese citizens who had the courage to speak their minds on the internet are in a Chinese gulag because Yahoo chose to reveal their identities to the Chinese government. It is beyond comprehension that an American company would play the role of willing accomplice in the Chinese suppression apparatus. My message to these companies today is simple: your abhorrent activities in China are a disgrace. I simply do not understand how your corporate leadership sleeps at night.

These enterprises, which have grown so powerful, so wealthy, so full of themselves, apparently have very little social conscience, apparently they don't appreciate their success is a result of a free and open and democratic society. What I am suggesting is that they do something in addition, merely, to doing business according to the laws of a repressive regime.