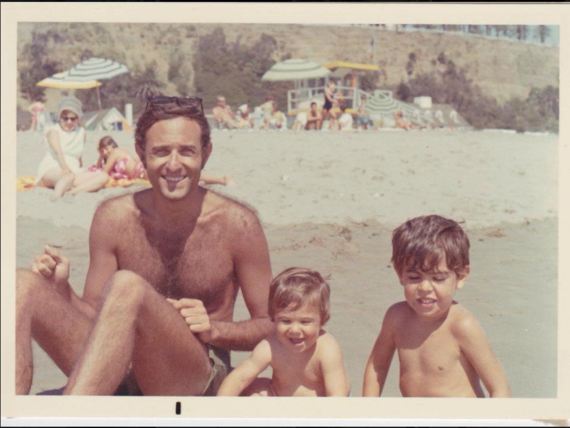

My dad seemed like he had a really good life. In my mind, he was always tan, smiling, playing tennis and wearing Fila -- the official uniform of suburban Jewish dads who smile and have a good life. One year, my parents went to China TWICE. Unless you're adopting a baby or Marco Fucking Polo, who goes to China twice? Richard Nixon went once. And he was known for Going To China.

For the first 42 years of my life, I believed my dad was the happiest, most well-adjusted person I knew: a pillar of strength and calm, with the rare capacity to take on everyone else's problems and let his own problems roll off his back.

In my 43rd year, he died by suicide.

For anyone who's lost someone by their own hands, you are asked to instantly imagine the unimaginable, to reassess everything you believed. And that's not even including the normal shock of "Wait, you mean I never get to see my dad again?"

In the weeks following my dad's passing, I experienced unbearable sadness and equally unbearable absurdity. Members of my extended family showed tremendous grace, kindness and compassion. Other times, they made August: Osage County feel like the Teletubbies

If I learned one thing, it's that there's no playbook on how to survive a tragedy. And if there was, a family member trying to postpone the funeral because he had Laker tickets probably wouldn't be in it. Then again, it was the playoffs...

Let me start with the obvious: There is no "good way" to hear that a loved one has taken their own life. That said, a particularly not good way is when your mom calls to say, "Dad killed himself," you keep hearing: "Matt killed himself." "Dad." "Matt?" This goes on for much longer than I'm proud to admit. It's the worst moment of my life. And it was revealed to me in an Abbot and Costello phone bit.

On the shocked drive to my parents' house, my mind desperately wanted to believe this was all a big mix-up. Until I saw my family home was a crime scene. With paramedics and a body bag. Then I started to believe it.

Still, that can't be my dad. He was at my house two days earlier, bringing my daughter a present for her ninth birthday. You don't do that if you're about to end your life, do you? And he hugged me goodbye. Did he know then that was the last time he'd ever hug me? I sure didn't.

I remember family members dropping everything to be by our side. I remember being so nervous talking to the police that I couldn't stop saying "foul play." I remember going forward with my daughter's swim party two days later, even though I was passed out inside from grief, because life had to go on. I remember eating chocolate chip pancakes and sausage from IHOP every day for a week and still losing five pounds.

There was no note. Or apparent explanation. People would say, "I hope you discover he was dying of a terminal illness only he knew about." "Thank you? That's kind of you to say."

A clearer picture began to emerge in the coming days. Debt. A house underwater. A financial situation that he'd shared with no one. Turns out, he had assiduously crafted a facade of continued wealth and well-being. And went to great lengths to present himself as he always had been; the rock, the provider.

That week also featured a legendarily contentious pre-funeral meeting in the rabbi's office, that culminated in a chorus of intra-family f-bombs. I'm pretty sure the rabbi had survived mortar shells near the Golan Heights. But a half hour with the Jewish Addams Family and his body language screamed "Get me outta here. Send in the cantorial intern!"

Ironically, what nearly broke me was a box of chocolates.

I needed a break from fun stuff like reading suicidal survival handbooks and making cremation arrangements. So I took my kids to see Kung Fu Panda. In the middle of the movie I get a call from my mother "Bryan, you need to come over right now. It's an emergency." Me: "Oh no! What is it?" Her:"It's your brother." Naturally, I assumed the worst. Her: "He just opened up a box of Sees Candy." Me: "Oh my God, I'll be right there.... Wait, did just say "Sees Candy'?" Unless he hand-dipped each piece in Strychnine, I'm not sure what the emergency is. Her: "Bryan, you know my problem with portion control. If he eats one piece in front of me, I'll eat the entire box."

I get a second call, on call-waiting. It's my brother, who's standing as close to my mother as you are to your computer screen. He wants me to intercede on his behalf. " A 32-year-old man should be allowed to eat chocolate." Hard to argue with that.

I'll admit, there were days that seemed like Grey Gardens: Encino Edition. But what I've come to accept is that these weren't characters playing the roles of grieving family members. These were real people experiencing real tragedy in real time. There is no right way to grieve when your world is turned upside down. Although in my opinion, it should always involve Sees Candy.

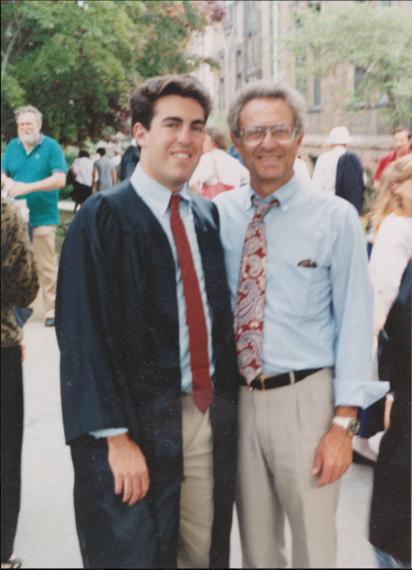

I had one goal in delivering my dad's eulogy: I didn't want his life to be defined only by the way it ended. I told of the man who picked me up in the middle of the night when I couldn't hack it at debate camp, who loved nothing more than standing at the bottom of the stairs while his grandkids pelted him with stuffed animals. He loved it, because they loved it.

There is no one to "blame" for a suicide. But I've often wondered: Should I have known more? He'd become quieter, but I had attributed that to the natural vicissitudes of aging. Would he have been more forthcoming if I didn't have my own financial problems? I know it wasn't my fault. It's no one's fault.

I'm no expert, but I think my dad ultimately died from shame: shame that he could no longer be the provider and protector he expected himself to be. A shame so overwhelming that he was past the point of being able to ask for help.

I have no idea if this a common dream amongst suicide survivors, but I have it a lot. In my dream, my father is alive and in the same house with my mother. In the dream, we're also aware that he had attempted suicide. We know all the things we later learned. His pain. His fragility. And we all try to keep him safe, to help him work through it. We know the full extent of everything he was going through. But he's alive.

And sadly, that's how I know it's a dream.

________________________________

Need help? In the U.S., call 1-800-273-8255 for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.