Hidden ruins are customary in the wild jungles of South America or on the white shores of the Mediterranean Sea. Now, researchers have uncovered a long-lost culture closer to Western civilization—in New England.

Today, southern New England is shrouded by lush forests, whose autumnal colors attract thousands of tourists and hikers each year. Urban hubs—Boston, Providence, Hartford—are peppered throughout. Rewind the clock 300 years, however, and the landscape would be unrecognizable, with much of the wooded countryside replaced by hundred-acre farms. Agriculture was king in New England until widespread industrialization in the 19th century led farmers to abandon their fields and move to cities. The forest stirred and soon reclaimed the disavowed land, cloaking the structural relics of a vast agrarian past.

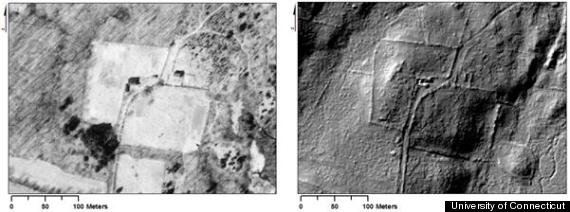

Left: 1934 aerial image, Right: 1m resolution DEM derived from LiDAR.

Left: 1934 aerial image, Right: 1m resolution DEM derived from LiDAR.

In a new study, which will be published in the March issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science, geographers Katharine Johnson and William Ouimet of the University of Connecticut, Storrs, uncovered these preserved sites without ever lifting a shovel. Using aerial surveys created by LiDAR, a laser-guided mapping technique, the team detected the barely perceptible remnants of a former “agropolis” around three rural New England towns.

Near Ashford, Connecticut, a vast network of roads offset by stone walls came to light underneath a canopy of oak and spruce trees. More than half of the town has become reforested since 1870, according to historical documents, exemplifying the extent of the rural flight that marked the late 1800s. Some structures were less than 2 feet high and buried in inaccessible portions of the forest, making them essentially invisible to on-the-ground cartography.

In rural Westport, Massachusetts, modern property boundaries overlapped with weathered stone walls that were unveiled by LiDAR. By examining historic maps from the early 1700s, the team learned these demarcations had barely changed over the centuries.

The untold consequences of this agricultural abandonment on the modern ecosystem are another story told by LiDAR archaeology. Invasive plants like Japanese barberry shrubs capitalized on abandoned open fields that were reverting to forests. Native species benefited as well. White pine, an aggressive timber species, gained a foothold in New England in the mid-19th century through the mid-20th century as farms were abandoned, says ecologist David Foster of Harvard University, who was not involved with the work. “The basic fact is the history of a site strongly influences the environmental conditions and the type of vegetation that develops,” he says. “Therefore, it ends up having a legacy of impacts on the vegetation today.”

“This fabulous work opens the eyes of people like me and other researchers,” says Foster, who plans to use LiDAR in his future investigations of forest ancestry in Massachusetts. It shows “that with relatively little effort, you can generate a completely new data set of information about the landscape.”

Discoveries like a dam and the forgotten walls of a once-buzzing sawmill near Tiverton, Rhode Island, will help quantify the impact that English-style agriculture had on the continuity between historic and modern landscapes, Johnson says. Studying vegetation dynamics near the sites could create a living history of the ecosystem, she says, that explains how much earth was moved by farmers or how humans impacted river systems in the past to guide land conservation in the future. She will also help historical societies document new landmarks. Given that some ruins reside on private land, this mapping will preserve a fuller historical picture, in case the land is ever sold and developed, she says.

This story has been provided by AAAS, the non-profit science society, and its international journal, Science.