"I wasn't born your mother." I said this in another recent post. It seems like a no brainer, but somehow, between the time they exit our stretched-out, forever-changed bodies, until the time they begin to actually look and act like adults themselves, or have their own children, this message is lost in translation. Our kids think we are their parents, and there was nothing before. It's not hard to see why. We live our lives in a complex dance in which we generally lead, and they follow. We're not their friends, but their mentors and guardians, their caregivers, their cheerleaders, their parents. By the time they're adults and starting to see things a little differently, these roles are seared on their brains, and we hope, their hearts. It's nearly impossible for them to comprehend that there was really a life, or that we were a person B.C. -- Before Children.

But we were -- people B.C. We were once children, in similar shoes. We grew up and had our own challenges and experiences. We fell in love; we probably had our hearts broken. We went to school and eventually had jobs; we learned to pay bills and navigate life. We loved our parents, or didn't, but inevitably had our own challenges there. We all went out there and had a single pivotal relationship that led to our role as parents.

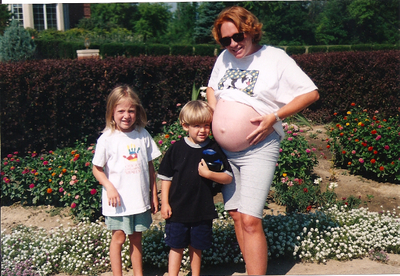

I can't speak to being a father, so I'll stick to what I know best: I'm a mother, a good mother; but I was not born one. I had an entire life before this. As my three kids: a daughter, 25, and two sons, 23 and 18, venture into the grown-up pool, they're asking more about how I managed those passages. I was not born a mother, and that fact is coming back to the forefront, as I'm challenged to rely on what I learned B.C.

Inevitably our kids venture out into that big world, and it can be helpful for them to see that we ventured too. Sure, the world has changed a lot since then, but despite any differences, we had to navigate many of the same things. Hearts break the same way; pain is pain. The "real world" can be overwhelming and scary, certainly challenging at the least. Money must be made; bills must be paid, and their lives unfold and take form, just as ours did: bit-by-bit- trial by fire.

Who is more uniquely qualified to advise and bear witness to their journey, than us? We have known them since conception. What mother can't still recall the amazing intimacy they felt with their babies, even before birth? We, as parents, if we are clear about boundaries and open to truths, care in a way that takes in who they were, who they are, and who they aspire to be... balanced against the razor sharp edge of what we hope for them.

As I've entered into this new phase with all three of my children, I've discovered a powerful truth that has been exposed over the past few years with my daughter, in particular, but more and more with my sons as well: We all have our own journey, but while we may have traveled the same road for much of that journey, we did not necessarily take away the same meaning, lessons or message. As I hear my kids label and describe their experiences: as siblings, as our children, and as their unique selves, I'm hearing that they were on the same ride, but often translated events and relationships very differently.

An example: I was raised in the Christian faith. I was raised weakly in that faith, at best, but Christian nonetheless. In my 20s, I fell in love with and married a man who was Jewish, and eventually we had three children. When my husband asked that we raise our children in the Jewish faith, honestly, I gave it little thought; I said yes. I took a conversion course, didn't convert, but threw myself into being the best Jewish mother I could be. We went to temple; we had friends in our synagogue; we celebrated the Jewish holidays, and we raised our kids to identify as Jews. I taught them the Sh'ma (link), the holiest prayer in our faith. To do that, I learned it first, and embraced it -- believing that I could not truly teach something that important, if I didn't feel it. In fact, four years ago as I sat beside my dying mother, in that moment when she was taking her last breaths, I instinctively sang the Sh'ma. My mother was not Jewish, but that prayer felt like the only thing to say in that moment. All of this to say: I believed I was raising my children as Jews, and that I was doing a really good job of it. For the record, I believed in and felt everything I was doing, as a Jewish mother, authentically. It wasn't forced.

Flash forward 22 years, and our oldest child, our daughter, decided to move to Israel. That would have been hard enough for her father and I, and the rest of our extended family, but because I never converted, and Jewish identity is determined by matriarchal bloodlines, my daughter was not considered a Jew in the eyes of Israel -- something required in order to gain citizenship. She embraced her faith fully, and spent some time living in the Orthodox community. Hard does not begin to cover that decision and its impact on all of us.

However, as she went deeper into her journey, I was stunned to hear her tell me, more than once: "You and dad didn't really raise us as Jews." By conservative standards, this is true; I can't deny it. However, over time these comments and her perspective took on a more challenging and painful tone for me. This indictment strikes at the heart of all I've done, all I've given up of my own family history and identity, all that I believed I had done to raise her as Jewish. How could she say this, let alone believe it? And so, after we'd had a few difficult arguments, and after I'd stopped feeling defensive and hurt, and finished licking my wounds ... I began to listen to what she had to say. That was when I realized that the lessons we hand to our children, the messages we believe we are giving, and sometimes the very experiences that we all shared together, are not always seen and experienced the way we intended or believed they were delivered. As she shared her thoughts, it became very clear that my girl had digested some things very differently than I thought I'd served them.

As we began to share more life stories, and lessons, woman to woman, this theme came up over and over again. The stories she'd told herself, or the ways she'd interpreted shared experiences: whether they have to do with faith, her relationship with her siblings, her role in our family, gender issues, how she thought we saw her -- countless things, were very different than the messages I thought we were sharing.

How did my endless efforts to infuse our family with Jewish values and tradition, become a life without God or religion? When did difficult, but normal, sibling issues become painful lessons about men and women? When did their father's efforts to get home and read bedtime stories whenever he could -- translation: occasionally -- while I did every "Mommy and me" class, drove to soccer/dance/religious school/was class parent/PTSA/chaperone/ad finitum, become "Dad was always doing things with us; you didn't really like that kind of thing?" That last one landed like a slap across my face, when one of my children expressed it -- stated as a fact, without any tangible anger. When did my constant belief in each of my children and their infinite potential translate to a lack of encouragement? It boggles this aging mother's mind.

And so it had to happen: I had to look at these twists in the road, with my almost adult children, and accept that their interpretations do not always match mine. This has been a jumping off point to begin forging new adult relationship with them. Recently I have listened more carefully to their stories, their versions of our shared journeys, and I've tried to sit with what they have to say. I'm working on letting some things go, and speaking up only when the gap seems important. I'm trying to accept that somehow some things were in fact lost in translation. If I didn't say it right, or they experienced it differently, I need to accept that this is where we landed -- right here, in this new reality.

I try not to take it personally, though it's really hard sometimes. I did tell my girl not to ever tell me I didn't raise her or her brothers as Jews again. It's not true. It's true within the constraints of the new life she has chosen, but it's not a cold hard fact. I have set her and her brother straight on a few key details that needed setting straight, and I've shared the truth, that while they may have taken certain lessons differently than we intended or hoped, the way things truly happened can not be re-written, we simply experienced them differently.

The truth is: her brothers were boys, and they acted like boys. They didn't always do things the way she wanted or would have liked, and they were sometimes insensitive. But, they also loved her enormously and were there for her. She didn't always do things the way they wanted, and she was sometimes insensitive as well. No matter how much my middle son has interpreted his role as middle child, as less fair, less, less, less than his siblings, it's never been true. No matter how much our youngest believes that we don't have as much faith in his abilities as we had in his older siblings', that's not true either. I have favored each of them, at various times in their lives, or in moments when they might have needed it, but I have loved each of them fully and without limits.

Nothing I did as a mother, or my husband did as a father, was intended to hurt our children, or leave "scars." It may sound cliché, but we all did our best. The fact that our children translated some things differently, the fact the our very best of intentions and our deepest hopes of imbuing our children with certain truths was not always received as intended, leaves us all in a uniquely new world, as we all approach each other on adult levels.

As a mother, the journey has been on a fairly predictable path for the past 25 years (no matter how unpredictable young children and teens seemed in the moment), but now, all bets are off. My daughter is expecting her first child any day, and she too will learn that translating the enormous, complex ball of emotions, dreams and hopes we all have for our children is not always a clear path. We do our best, and hope it all works out in the end. I listen patiently as she explains childbirth to me, knowing that in the next few days, her perceptions may change. I smile when she tells me the latest on how babies should be cared for. Her baby will spit up, and cry, and poop, and eventually smile, just like mine did. In a few weeks, she will have just an inkling of how much I love her, and how much I have always wanted to do my best. It will be joyous to watch her take those first steps down this path.

I was not born their mother, and more than ever before, I am drawing on that fact, my history B.C., to tap into their worlds -- where they live now. I am drawing on who I was when I wasn't their mother, to understand how they feel now, and how we'll all go forward. We're not lost, we're all just working on a new translation.

* * *

If you enjoyed this post: Hit the little thumbs up at the top; and make me smile. Like it; Share it. If you'd like to read more of my work, check out my blog Tales From the Motherland, or follow me on Twitter and Facebook.

Earlier on Huff/Post50: