"It's not Rocket Science," is a statement often -- and quite boringly -- made by those pretending to humility about whatever it is they do. Often it is celebrities mouthing this statement, show biz people who live with an abundance of attention, which most likely has gone to their heads, but damn if they are going to let you know that. The irony of it is that rocket science rests on a solid and known foundation of mathematics and physics, whereas the creative arts -- with which one entertains others -- are somewhat magical, ephemeral, unquantifiable, and essentially mysterious. As it was once famously stated, "Dying (which also rests on a solid foundation of physics) is easy; comedy is hard."

The statement, "It's not Rocket Science," has less to do with the comparable complexities of achievements than it does with the fact that rocket science, despite resting on that solid and known foundation of mathematics and physics, is still to most laymen an arcane and unfathomable practice done by a coterie, possibly a cabal, of the Elect who are just simply not like you and me.

The nascent years of this condition were during the end of the Second World War when finned and needle-nosed rockets blasted off the covers of science fiction pulp magazines and landed with a bang onto London. Its not-steady-on-its-legs toddler period came right after the war when we took those rockets made in Germany and put them in New Mexico to see what made them work. It grew strong and robust in the '50s and '60s when rocket dreams and hopes and entertainments and anticipations had them taking us to the stars to land on alien planets to sometimes face monsters, or taking H-Bombs to foreign lands to annihilate the enemy or create monsters from our worse insect nightmares. Maturity came with real world triumphs and tragedies, footprints on the moon; space trucks blowing up, snapshots from the surface of Mars and from within the rings of Saturn. All of this made the rocket scientist either a hero or a villain, but in either case, a genius member of a secret society. A genius because only a genius could take us to the stars or deliver a death blow upon our planet. A secret society because most of us know that we will never be invited to join.

And yet, this cannot be an accurate picture of the situation, can it? It is more gut reaction than mindful consideration isn't it? Figuring out an accurate picture cannot be that hard can it? I mean -- it wouldn't be rocket science would it?

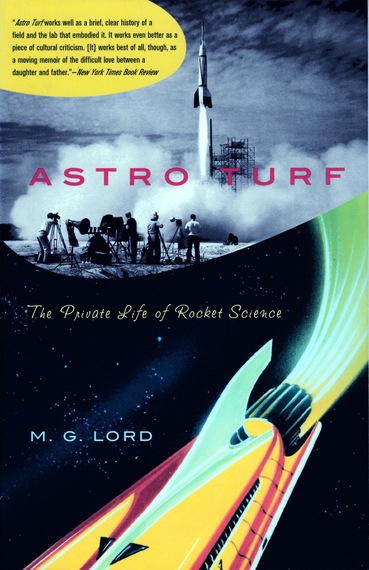

But it does take that mindful consideration, which is exactly what M.G. Lord delivers in her fine 2005 book, Astro Turf: The Private Life of Rocket Science.

I had long wanted to read this book as I have enjoyed Lord's appearances over the years as both panelist and moderator at the L.A. Times Festival of Books.

She contributes smartly to such events, and is often funny (in fact, she has done stand-up comedy and she was once a political cartoonist), and her charming intelligence is always well-displayed. All these attributes can be found in Astro Turf .

At first glance it does not seem as if Lord would be the obvious author of such a book. A cultural critic and investigative journalist, her book previous to Asro Turf was about a plastic doll, Barbie, and her subsequent book was about a "living doll," Elizabeth Taylor, both books delineating their cultural significance. But Lord came naturally to the subject of Astro Turf as her father, Charles Lord, had been a rocket scientist. Or, rather, a rocket engineer -- an applicator of rocket science. He was not as important to American rocketry as he might have led his family to believe, but neither was he as insignificant as Lord once may have thought. What he definitely was though was a man dedicated to, possibly obsessed with, his work. This made him a good rocket man, but not necessarily a good family man, especially after the premature death of his wife from cancer, when Lord was a teenager. In order to understand her father, maybe get close to him as neglected children often want to do, Lord felt it was important to understand the profession her father retreated into. And for which, in her younger mind, he had been the symbol of: A white manly man member of that secret rocket society; a straight arrow in white dress shirt, possibly short-sleeved, possibly with a pocket protector.

What Lord discovered in her research into the history of rocketry was that rocket scientists and engineers were often as complex as the machines they designed and built, that some of them were not really manly men, and that some, later in the history, were not -- thank goodness -- men at all. She discovered that some of them, especially in the early days, had ideas that were even odder than that of flying to the moon. Some of those ideas were truly odd, bordering the occult. Some were odd only in the opinion of certain others, being ideas, for example, slightly socialistic or, to put it another way, compassionate towards the downtrodden. She discovered that participants in rocket science, often portrayed in the mass media as near robot-like individuals, were quite familiar with a range of emotions as they suffered ironic hounding and persecution or prejudice for possibly being fellow travelers with dreaded Communists, or being homosexual, or -- for some, the worse thing of all -- being a woman who wanted to be a scientist or engineer and to contribute to our view and understanding of the stars. Ironic because the powers-that-be who looked upon such individuals with the askance glance of disapproval, if not complete condemnation, were often the same powers-that-be that had welcomed with open arms ex-Nazi scientists and engineers, some of whom had resumes bordered in black.

And she discovered that the road they were really all fellow travelers on was a road to a future they had all dreamed about as children, a future once announced in science fiction that they were trying to find the science facts for. It is a future demanding dedication, possibly obsession, which is often detrimental to home life. But it is also a future of widening knowledge, of deeper understanding, and of an opening up of the universe. Does aiming for that future excuse domestic faults? Possibly not. But it does bring some perspective to them.

Through her research and reporting Lord comes to an understanding of her father, maybe even an admiration for him. Certainly she has an admiration for rocket scientists. Not because they are almost superhuman with special and arcane knowledge, but because they are deeply human -- male, female, light skinned or darkly hued, gay, straight, odd or even "perfectly normal" -- vanguards who not only love the game of getting things to work and work well (the rockets), but anxious for and willing to be awed by the knowledge that is often the outcome of the game (the science).

In looking for her father, a personal quest, Lord found a fascinating history that should be personal to us all. It would be nice if the statement, "It's not rocket science," came to be used not to distinguish the easy from the difficult, but rather the mundane from the marvelous.

Astro Turf is still in print and is also available as an ebook at your leading online booksellers.

Steven Paul Leiva's latest book is By the Sea, a comic novel. He has previously mused on rocket science in his science fiction satire, Traveling in Space.