The first time I picked up the book $tud, first published in 1966 by a writer with the intriguing name Phil Andros, I knew I had come upon something truly unusual: a literate porn author. Here was the hilarious tale of a cocky male hustler who made no bones about his illicit profession, nor his countless erotic encounters. Phil Andros was a macho rebel and a proud gay man writing at a time when many similar stories were still drenched in shame and guilt.

Little did I know at the time that Phil Andros was actually the pseudonym of a skinny, slightly indigent, old man, named Samuel Morris Steward, who lived alone in a run-down section of Oakland. The writing was so engaging and realistic that I had assumed he was everything he said he was on the page -- a sort of Tom of Finland drawing come to life (Tom of Finland, in fact, had done the cover illustration). But in a deeper sense he was. Because Steward himself was a sexual renegade, a pioneer who pushed the boundaries of gay literature, and society, while living a life that was just as louche and homoerotic as any of his literary creations. He was also, I later discovered, a world famous tattoo artist, aka Phil Sparrow, a favorite of the Hells Angels.

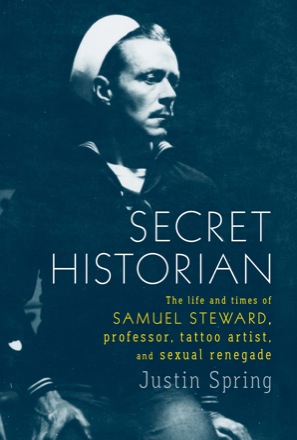

Now art scholar Justin Spring (Paul Cadmus: The Male Nude) has written a riveting new biography of Samuel M. Steward. Entitled Secret Historian -- The Life and Times of Samuel Steward, Professor, Tattoo Artist, and Sexual Renegade (Farrar, Straus, Giroux), the book is a revelation. Through in-depth interviews, access to Steward's voluminous private papers, and the Kinsey archives (to which Steward had been invited to contribute), Justin Spring has unlocked and exposed a world that until now was only hinted at by other writers.

Like the groundbreaking book Gay New York by George Chauncey, that shed light on a lost underground world, Secret Historian reveals a vital subterranean culture, thriving throughout the early part of the 20th century. Steward was there at key moments in queer history, a kind of homosexual Zelig. But in contrast to that inspired Woody Allen figure, Steward was an active participant, not just an innocent bystander.

Openly consorting with like-minded authors, teachers, students, artists and performers, pick-ups, and tricks, Steward kept detailed diaries and lists of all his sexual "conquests" and escapades in a box marked "Stud File." The liaisons number into the thousands. He also took photographs and filmed his sexual orgies. Considering that he could have been arrested and blackmailed for any of these indiscretions, it's remarkable that these documents survived. But Steward was a pack rat, saving every scrap that ran through his industrious fingers. He was encouraged in this endeavor by his good friend and guide, Alfred Kinsey, who saw in Steward an invaluable entree into the homosexual demimonde (to which he was himself drawn) and a unique example of a sexual gourmand, for want of a better word, for whom quantity was more important than quality.

Born in 1909 in Woodsfield, Ohio, Samuel M. Steward had gone to Ohio State University, then became a professor at Loyola, and later DePaul University in Chicago. In 1936, he published a well-received novel Angels on the Bough, about his family's life back home during the Great Depression. Armed with letters of introduction by well-connected friends, Steward went to Paris and met Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, with whom he became lifelong friends. He visited with them often at Bilignin, their country house, and wrote a memoir of that friendship and published a collection of their letters, Dear Sammy (1977).

Despite his connections, Steward failed to live up to his early potential. It was not until he penned his explicit Phil Andros stories (basically as a lark) that he achieved any real recognition. Later in life, he published a pair of amusing mystery novels, incorporating Stein and Toklas as sleuths, including the witty Murder is Murder is Murder (1985). These are feather-light entertainments, poorly plotted and implausible, but they provide a rare and invaluable hands-on insight into the private lives of these two titanic figures.

But literary failures aside, what a life he led! Samuel Steward luckily was at the right place at the right time so often that reading his biography is like gazing into a crystal ball, or being a fly on the wall in the boudoirs of the best and brightest of the era. Here we find Steward seducing Rudolph Valentino at the hotel he was staying in during a tour promoting one of his silent films. Later we find Steward in London, making love to Lord Alfred Douglas in hopes of creating a visceral link between the notoriously beautiful poet (then a wizened and unattractive older man) and Steward's great hero, Oscar Wilde.

At Andre Gide's in Paris, Steward beds the French writer's nubile Arab lover. Later in an elevator at a department store, the eagle-eyed Steward has a quick but memorable tryst with Rock Hudson, then a working class hunk named Roy Fitzgerald. There are hilarious escapades with Sir Francis Rose, the troubled British artist, whom Steward penned a novel about called Parisian Lives (1984). Perhaps Justin Spring's most surprising revelation is the extent of Steward's amorous relations with playwright Thornton Wilder, a closeted homosexual. After reading this book, it's hard to think of the author of the iconic Our Town, without envisioning Wilder engaging in frisky frottage in Steward's arms.

Steward was also a magnet for other gay writers and artists, including Jean Genet, Glenway Wescott, Fritz Peters, Tennessee Williams, Jean Cocteau and James Purdy, and perhaps most meaningfully, photographer George Platt Lynes, who shared Steward's fascination with the beau ideals of American manhood. Steward had an ongoing affair with one of Lynes's best-known models, and would often recommend his own "discoveries" in kind.

And then there is the second half of Steward's life when he gave up teaching to pursue tattooing. Spring shows how foolhardy a venture this really was, and how risky for its time. Tattooing then was not the popular art form it is today; it was the realm of shady characters, prisoners, and outlaws. For a gay man with a penchant for soldiers, sailors and rough trade to open a parlor in the roughest part of Chicago was a recipe for disaster.

At times Steward found himself in harm's way once too often, especially after he moved to Oakland and began working out of a ghetto. He was robbed often and also beaten. But Spring gives us insights into how Steward charmed his clientele, even when they were as volatile and violent as the Hells Angels.

Later Steward became active in the burgeoning gay porn scene on the West Coast, befriending J. Brian, who ran a magazine and film business. Through him, Steward got a steady supply of hustlers, and became intimate with Johnny Harden, one of the biggest adult entertainment stars of the 80s (both gay and straight).

Spring keeps an academic distance from his material throughout the biography. It would have been easy for him to make sweeping assumptions about Steward's various sex addictions, his chronic drug use (after giving up alcohol), his sado/masochistic tendencies, the obvious parallels of his hoarding, diary-keeping and punishing crushes, to today's trendy concepts of OCD. But that would diminish the impact of what is revealed here. Yes, Steward might have been a better writer (or at least a more productive one) if he had not devoted so much of his life to pursuing sex, or if he had not medicated himself later on with endless painkillers and speed (He died in 1993).

But Spring shies away from laying blame, passing judgment, seeking causes, or reading between the lines. He merely uncovers, then chronicles the events as documented, and thereby gives us a three-dimensional portrait of the man in all his guises, warts and all.