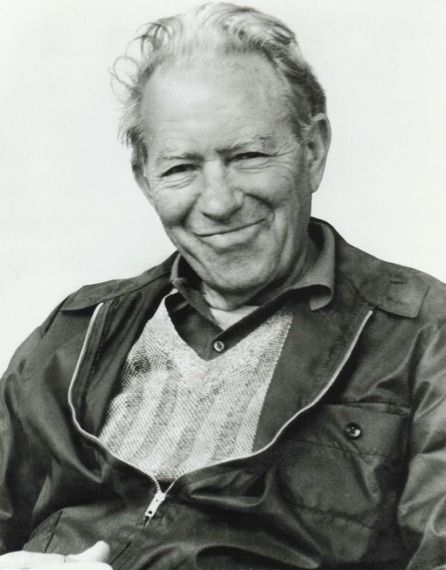

My friend Ernie Harburg and I are both sons of songwriters -- in his case, that songwriter was the transcendent genius Yip Harburg, who wrote the lyrics for such gems as "Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?" "It's Only a Paper Moon," "Somewhere Over the Rainbow" and all of the lyrics for the Wizard of Oz film and the Broadway hit, Finian's Rainbow.

Following is the conclusion of a two-part essay in which Ernie -- a Senior Research Scientist Emeritus at the University of Michigan Departments of Epidemiology and Psychology with over 85 scientific articles to his credit (and the President of The Yip Harburg Foundation, dedicated to Yip's vision of social justice) -- traces his deep connection with a father whose mind embraced the beauty of poetry and science. (Part 1 can be found here.

----------------

By the '40s, I had moved from Brooklyn to live in Yip's new house in Brentwood, CA and attend Beverly Hills High School. This was like leaving Coney Island on a hot day and instantly living in Star Wars! One day Yip took me to a restaurant where there were white tablecloths and sparkling utensils. I had my hand around the glass when the waiter poured the water in, and I noticed that suddenly my fingers were puffed up. I said "Look, Yip. Look at my fingers. What is that all about?" And Yip said, "Well, "the light wave coming from the sun goes through the water and it's refracted and bent and that's what causes the distortion, so your perception is non-veridical." Zing!

Yip had earned a B.S. -- not a B.A. -- at City College of New York. He was forced to take trigonometry and calculus. His friend Ira refused to do that and dropped out (his brother George had already dropped out of high school). Years later I too got a degree at City College, taking required courses in calculus, physics and chemistry. I too learned about the Bernoulli Principle, the refraction of light, and chemical equilibrium --and I felt attuned to Yip's scientific mind.

That scientific mind -- the knack for problem solving -- was essential to Yip's lyric writing. After all, a lyric is built upon a matrix of melodic notes and chords which starts from an unconscious place -- an "artistic key"-- a title. The song "April in Paris" actually has only 66 words. The lyricist -- in collaboration with the composer -- fits these words into a melody with chords to craft a "song." The team has to be disciplined and creative, rigid and fluid. It's like explaining your research in an article, or Yip's Anthem of the Great Depression in two verses:

They used to tell me I was building a dream,

And so I followed the mob.

When there was earth to plough or guns to bear

I was always there, right there on the job.

They used to tell me I was building a dream

With peace and glory ahead.

Why should I be standing in line

Just waiting for bread?

Yip had a scientific mind as well as a poetic one. So when he learned that his son had received a Ph.D., he was flabbergasted. While his mother had given birth to ten children, only four of them survived; but one survivor was his oldest brother Max, a genius who became a professor of physics at age 28! Max was doing research articles about the speed of the earth around the sun and Yip and his parents -- my grandparents -- were poor first-generation immigrants who didn't know what to make of it. They were awestruck by his scientific status; but within a month he got cancer and died. Yip adored Max and was impressed by his science; from then on, he became a secular thinker, which in turn influenced deeply my own perspectives about life, the universe and research.

In the Fifties, Yip got hit by the House Un-American Activities Committee anti-communist "witch hunt" and was "blacklisted" from film, radio and TV. We were helped by Yip, who said, "While life is hopeless, hopeless -- it's not serious."

When I became a research scientist and I had done a large study in Detroit in the Sixties about black-white anger and blood pressure, the New York Times printed that "Dr. Ernest Harburg did blah blah blah." To Yip this was like Moses coming down with the Commandments. He regarded me almost with reverence as a scientist. And I felt relief that he was off the blacklist and continuing his lyrical activism. The playing field between us was leveled.

By the late Seventies Yip felt mortal for the first time. He had never confronted his death before. We knew he would die soon because he had angina, arrhythmia, intermittent claudication, atherosclerosis and he was taking nitrogen pills and he didn't want to face up to this.

Marge and I and a cousin created the legal basis for two organizations, The Yip Harburg Foundation and the Glocca Morra Music Publishing Company so that the money -- royalties from his lyrics -- would come in and go to the foundation, which is still dedicated to peace and social justice. We presented the documents to Yip. He was visibly touched and I said, "And so, Yip, we're giving you a gift of an elegant legacy" (one of his lyrics: "I've an elegant legacy waitin' for ye"). I saw a tear and a twinkle in his eyes, simultaneously. Then he leaned back in his chair and said, "Oh come now, you're pulling my legacy."

Months later, in the spring of 1981, Yip did indeed die. And years later, as I was sitting alone at night in the then-newly established Yip Harburg Living Archive at New York University (since moved to Lincoln Center) sorting through old papers, I suddenly came across a note in Yip's unique handwriting which said "And Ernie! ... A Ph.D.!! ... I thought he'd be a sand-lot pitcher!!!" I started laughing so loud that I was ejected by the guard!