In Europe and the United States, this mushroom (Grifola frondosa) is commonly called "hen of the woods," since its frond-like growths resemble the feathers of a fluffed chicken. Maitake is the name I prefer, in a bow to the Japanese who pioneered its cultivation. Maitake mushrooms are known in Japan as "the dancing mushroom." According to a Japanese legend, a group of Buddhist nuns and woodcutters met on a mountain trail, where they discovered a fruiting of maitake mushrooms emerging from the forest floor. Rejoicing at their discovery of this delicious mushroom, they danced to celebrate. In Italy, this species is known as signorina, or "the unmarried woman." Today these two common names, bestowed long ago on the opposite sides of the planet, seem especially deserving and perhaps foretelling recent research findings.

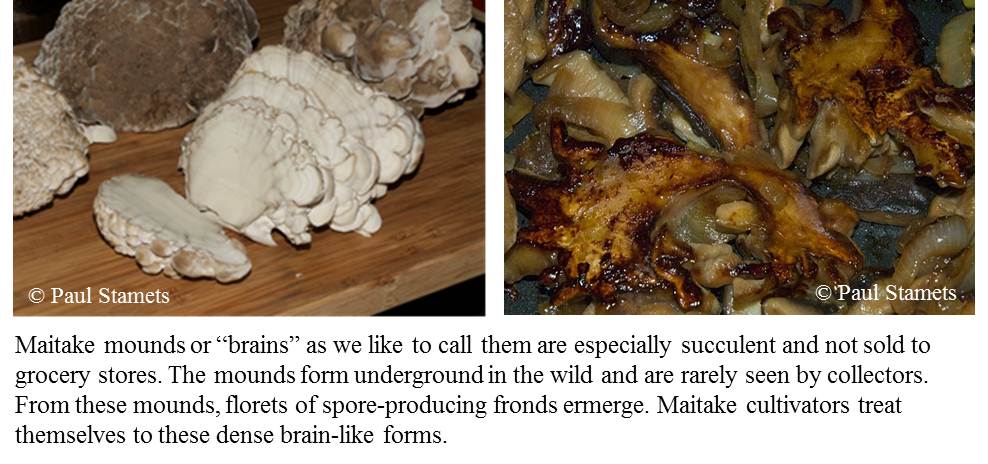

Maitake is a soft polypore mushroom (many other polypore mushrooms are hard woodconks), making it one of the few of that group you can cook with. Maitake mushrooms are indigenous to temperate hardwood forests and are particularly fond of oaks, elms, and rarely maples. Feeding upon the dead roots of aging trees, maitake mushrooms emerge from dark grey mounds that form a few inches under the soil at that base of the tree. From the underside of their flaring leaf-like protrusions, white spores dust the ground below or are sent adrift into the wind.

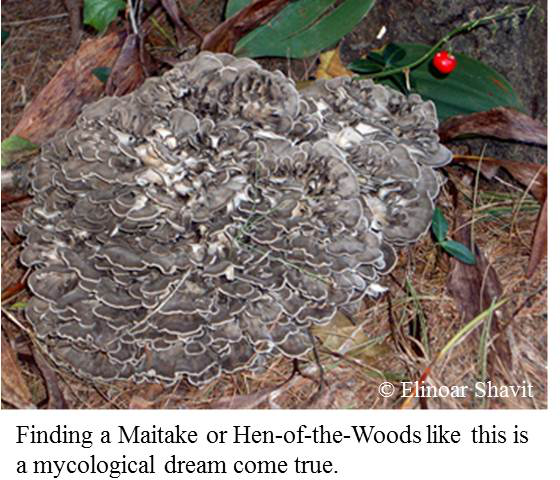

Maitake can achieve humongous sizes, sometimes up to 50 pounds per specimen! Massive maitake can form annually from dying dendritic tree roots for many years, even decades. The locations of these robust patches are often family secrets passed down from one generation to another, and for good reason! I know of one Italian-American family in New York who boast of maitake bonanzas that would seem unbelievable if were not for their annual yield of photographic evidence of giant maitake. More often than not, they fill their cars to the brim, while leaving the majority of the maitake in the woods.

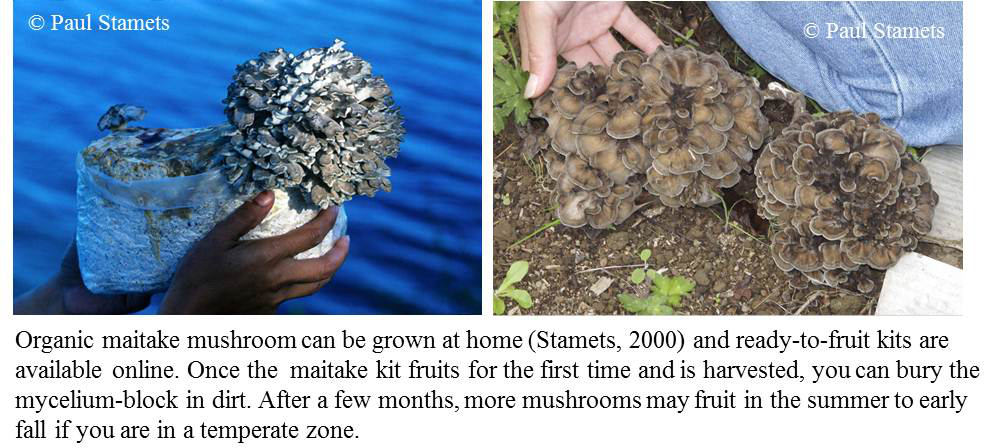

As a cultivator, I am naturally envious, since cultivated maitake rarely grow to clusters weighing more than a couple of pounds. Two advantages of cultivated maitake, however, are that they are cleaner -- free of the forest debris that typically becomes embedded within the uplifting fronds of wild ones -- and that they can be grown at home all year long.

My family is delighted every time I cook maitake. Our taste buds awaken in anticipation of its rich, deep and nuanced flavors. Maitake contains L-glutamate, a natural flavor-enhancer that provides umami -- the "fifth taste" -- the savory rich flavor that excites receptor-specific nodes on your tongue. Moreover, maitake is one of the healthiest foods around. In the past, mushrooms were maligned as nutritionally poor. Since they are about 80 to 90 percent water when fresh, their net concentrations of nutrients can be underestimated. Like grains, however, mushrooms should be weighed when dry to get their correct nutrient value.

- 377 calories per 100 grams dry weight

- 25 percent protein

- 3-4 percent fats (1 percent polyunsaturated fat; 2 percent total unsaturated fat; 0.3 percent saturated fat)

- ≈60 percent carbohydrates (41 percent are complex carbohydrates)

- ≈28 percent fiber

- 0 percent cholesterol

- B vitamins (mg/100 g): niacin (64.8); riboflavin (2.6 mg); and pantheonic acid (4.4 mg)

- High concentration of potassium: 2,300 mg/100 g (or 2.3 percent of dry mass!)

Medicinal Properties

As a medicinal food, maitake has several notable attributes. Foremost, several studies show it modulates glucose levels, which can be especially important for limiting the development of Type 2 diabetes (Kubo et al., 1994; Konno et al., 2001; Preuss et al., 2007; Lo et al., 2008). Diabetes causes neuropathy, renal (kidney) disease and retina degeneration. Nearly 8 percent of Americans have diabetes -- and this trend is accelerating. It is the seventh leading cause of death in the U.S. Although this preliminary evidence looks enticing, robust clinical studies are needed to prove effectiveness for diabetes control in humans. Since the use of these mushrooms for this purpose cannot be patented, funding will have to come from government grants or private sources.

Maitake has also been widely researched for its effects on the immune system and various cancers. Several researchers corroborate that maitake causes apoptosis ("programmed suicide") of cancer cells and contains anti-angionenesis properties. That means they can restrict the proliferation of bloods cells that feed tumors. One reason may be that maitake mushroom fruitbodies are rich in complex polysaccharides, in particular the heavy and complex 1,3; 1,4; and 1,6 beta-D-glucans. In an interesting development for the dietary supplement industry, Wu et al. (2006) found that the mycelium of maitake produces a greater array of lower molecular weight sugars and exopolysaccharides (heteromanans, heterofucans, and heteroxylans) than the mushrooms. These molecules are known to activate significant immune responses, enhancing the ability of immune cells (neutrophils and natural killer cells) to kill and consume lung and breast cancer cells (Deng et al. 2009; Lin, 2011).

One portion of these complex sugars, known as maitake's "D fraction" (a type of beta glucan) shows activation of a host defense response by stimulating proliferation of some immune cells. Since activity of these cells has also been documented with non-fractionated samples, other immune activating components are likely to be discovered in maitake besides this one form of beta glucan (Kodama et al., 2010; Stamets, 2003). However, in a 2009 critical review of the cancer-fighting properties of maitake by Ulbricht et al., the authors found the data intriguing but not necessarily convincing due to ambiguities in the design, reports, and markers used in the clinical studies to date. In other words, the jury is still out on whether or not maitake will significantly improve a patient's survival from cancer.

What this means for health-conscious consumers is that while maitake's use as an adjunctive treatment for cancer remains a topic of medical debate, both the maitake mushroom and its mycelium contain a constellation of active constituents that bolster human health via many complex pathways. These metabolic pathways work synergisitically to improve host defense. Isolating one consitutent from the others denatures and lessens the broad-spectrum potency of this natural, functional food.

Maitake's complex sugars, very low fat (

Now we know that the Japanese woodcutters and the nuns did indeed have reasons to dance for joy when they found maitake, the "dancing signorina" mushroom!

Financial Disclosure: Paul Stamets, author of Growing Gourmet & Medicinal Mushrooms and educator of mushroom cultivators world-wide, is also the Founder of Fungi Perfecti, LLC -- a company that supplies mushroom related products including whole, encapsulated powders, and extracts of mushrooms.

References:

Chen, J.T., Tominaga, K., Sato, Y., Anzai, H., Matsuoka, R. 2010. "Maitake Mushroom (Grifola frondosa) Extract Induces Ovulation in Patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Possible Monotherapy and a Combination Therapy After Failure with First-Line Clomiphene Citrate." The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. Vol. 16, No. 12, p. 1-5. Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. DOI: 10.1089/acm.2009.0696.

Deng G., Lim H., Seidman A., Fornier M., D'Andrea G., Wesa K., Yeung, S., Cunningham-Rundles, S., Vickers, AJ, Cassileth, B. 2009. "A phase I/II trial of a polysaccharide extract from Grifola frondosa (Maitake mushroom) in breast cancer patients: immunological effects. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 135:1215-1221.

De Silva, D., Rapior, S., Hyde, K., Bahkali, A. 2012. "Medicinal mushrooms in prevention and control of diabetes mellitus." Fungal Diversity 56:1-29. DOI 10.1007/s13225-012-0187-42012.

Kodama, N., Mizuno, S., Asakawa, A., Inui, A., Nanba, H. 2010. "Effect of a hot water-soluble extraction from Grifola frondosa on the viability of a human monocyte cell line exposed

to mitomycin C." Mycoscience (2010) 51:134-138. DOI: 10.1007/s10267-009-0016-0.

Konno, S., D. G. Tortorelis, S. A. Fullerton, A. A. Samadi, J. Hettiarachchi and H. Tazaki, 2001. "A possible hypoglycaemic effect of maitake mushroom on Type 2 diabetic patients" Diabetic Medicine, 18, 1007-1010. Department of Urology, New York Medical College, Valhalla, NY, USA.

Kubo, K., Aoki, H., Nanba, H., 1994. "Anti-diabetic activity present in the fruit

body of Grifola frondosa (maitake)." Biol Pharm Bull 17: 1106-1110.

Li, William, MD. "Can we eat to starve cancer?" TED, 2010. Long Beach, California. Angiogenesis Institute, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Lin, En-Shyh, 2011. "Production of exopolysaccharides by submerged mycelial culture of Grifola frondosa TFRI1073 and their antioxidant and antiproliferative activities." World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, Vol. 27, No. 3, p. 555-561(7).

Lo, H-C, Hsu, T-H, Chen, C-Y. 2008. "Submerged Culture Mycelium and Broth of Grifola frondosa Improve Glycemic Responses in Diabetic Rats." The American Journal of Chinese Medicine, Vol. 36, No. 2, p. 265-285.

Matsuur H., Asakawa C., Kurimoto M., Mizutani, J. 2002. "Alpha-glucosidase inhibitor from the seeds of balsam pear (Momordica charantia) and the fruit bodies of Grifola frondosa." Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry 66 (7): 1576-8.

Patel, S., Goyal, A. 2012. "Recent developments in mushrooms as anti-cancer therapeutics: a review." 3 Biotech (2012) 2:1-15. DOI 10.1007/s13205-011-0036-2.

Preuss, H., Echard, B., Bagchi, D., Perricone, N.V., Zhuang, C. 2007. "Enhanced insulin-hypoglycemic activity in rats consuming a specific glycoprotein extracted from maitake mushroom." Mol Cell Biochem (2007) 306:105-113. DOI 10.1007/s11010-007-9559-6.

Stamets, P. 2000. Growing Gourmet & Medicinal Mushrooms. Ten Speed Press, Berkeley, Ca.

Stamets, P. 2003. "Potentiation of cell-mediated host defense using fruitbodies and mycelia of medicinal mushrooms." International Journal of Medicinal Mushroom, vol. 5, no. 2,

p. 179-192.

Stamets, P. 2005. "Notes on nutritional properties of culinary-medicinal mushrooms." International Journal of Medicinal Mushrooms, vol. 7, p. 109-116.

Ulbricht, C., Weissner, W., Basch, E., Giese, N., Hammerness, P., Rusie-Seamon, E., Varghese, M., Woods, J. "Maitake Mushroom (Grifóla frondosa): Systematic Review by the Natural Standard Research Collaboration." Journal of the Society for Integrative Oncology, Vol. 7, No. 2, p. 66-72.

Wu, M-J., Cheng, T-L., Cheng, S-Y., Lian, T-W., Wang, L., Chiou, S.Y. 2006. "Immunomodulatory Properties of Grifola frondosa in Submerged Culture." Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 54(8):2906-14. DOI:10.1021/jf052893q.

For more by Paul Stamets, click here.

For more on natural health, click here.