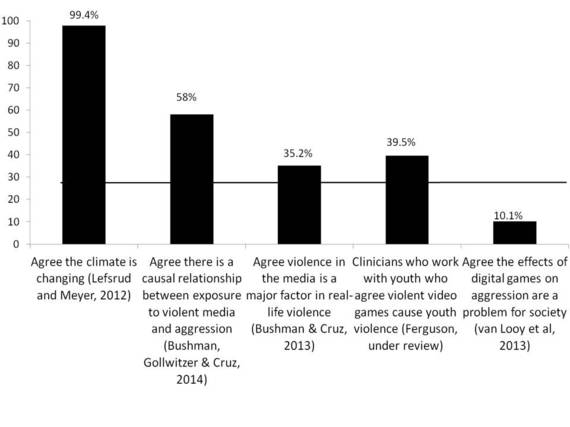

Scholars and the general public continue to debate whether media violence does or does not contribute to aggression or violence in society. As part of that debate, it's not uncommon to hear arguments about whether a scholarly consensus exists on the issue of media violence. Consensus isn't actually evidence of course... plenty of prior scholarly consensuses have proven wrong, particularly in social science. But the degree of consensus among climate scientists regarding climate change (about 99.4 percent) certainly is compelling. Scholars advocating the "harm" position of media effects often claim a similar consensus exists on the issue of media violence.

Increasingly, evidence suggests that is not the case, although that hasn't stopped some from making the claim. The most recent salvo comes from a study by Ohio State University. Briefly, this study surveyed scholars belonging to several specific groups (such as the Council on Communication and Media, a small group of pediatricians involved in media advocacy for the American Academy of Pediatrics). The majority of media scholars and pediatricians who did not belong to these groups were not surveyed, so it is imperative that potential selection bias be considered when interpreting the results. An online survey of parents was also considered. Results indicated that 58 percent of scholars agreed that media violence contributes to aggression (left undefined). Much higher percentages were found for the council of pediatricians (80.4 percent), with parents in the middle (64.7 percent).

On the question of whether media violence contributes to violence in society (arguably the question most people worry about) the results were different. Only a minority of scholars (35.2 percent) agreed with this, along with 72.9 percent of the small group of pediatricians and 57 percent of parents. So of the groups studied, on the issue of media effects, the scholars who actually study it are the most skeptical. The study authors still interpreted this as a "broad consensus" and compared their results to global warming (where, again, 99.4 percent of scientists agree).

This study has some obvious problems. Why were such narrow groups of scholars and pediatricians sampled? The pediatricians group is a very small group that presumably has had a hand in disseminating the American Academy of Pediatrics' policy statements on media. So they may very well be a group heavily invested in these particular beliefs and generalizing results from this small group to all pediatricians is, to say the least, premature. And why not just sample all media scholars, rather than just those belonging to specific groups? Presumably scholars self-select into these professional groups and the results may have indicated even more skepticism if opened up to all scholars.

Second, aggression was never defined. The concept of aggression means a lot of things to different people, and aggression is moderate doses is generally a healthy thing yet problematic at the extremes. I've spoken to scholars, for instance, who believe violent media might increase aggression in the same way that any competitive activity might... playing cards, watching sports, engaging in a debate... all activities we accept... and that any such aggression is nothing to worry about. Such a scholar might respond "yes" to the question on aggression, but "no" on the question of violence. Indeed the discrepancy in results between aggression as an outcome and violence in society as an outcome indicates some lack of clarity in the terms used.

But perhaps the greatest problem is the slipperiness with which the Ohio State study uses the term "consensus." The authors, in the study make references to the global warming consensus, but even taking their numbers on scholars at face value, they're off by over 40 points. At best, again at face value, they demonstrate that a small majority of scholars agree that violent media may contribute to (ill defined) aggression, but that only a minority agrees on the issue of societal violence. That's not much of a consensus.

Perhaps more critical, these results conflict with other sources of data. Last year, a sizeable group of 230 scholars wrote to the American Psychological Association, asking them to remove their policy statements on violent media. Other surveys of scholars and clinicians suggest that only a minority see violent media or video games as a societal problem. Similar with surveys of the general public. Such surveys with the public generally indicate split opinions along generational lines, with older adults who don't use newer media more likely to worry. Unfortunately the authors of the present study didn't ask scholars about their age. It would have been interesting to see if generational effects are present for scholars as well.

Ultimately, it appears that this study is of the sort that was conducted all along with the press release in mind before any data was even collected. Media violence is an emotionally valenced moral issue, and where social science is involved, it's easy for moral issues to cloud the quality of research studies. A study such as this may be motivated to stifle legitimate scholarly debate to suit a rigid moral agenda through claims of a false consensus. Studies such as this one with a manufactured "appeal to consensus" logical fallacy work against science, not for it.