In these days of Google Earth, GPS tracking, and instant cell phone connections to every nearby restaurant, mapping technologies inspire new visions. It's great to know about restaurants. What do you know about, say, moose? Or museums?

One recent evening at the National Museum of Wildlife Art, about two hundred people gathered for a potluck dinner with Bert Raynes, a much-beloved writer and observer of nature, particularly birds, in the valley of Jackson Hole, and a long advocate of wildlife. Bert founded the Meg and Bert Raynes Wildlife Fund after the death of his wife, Meg, to identify and support wildlife and habitat preservation in Jackson Hole and Wyoming.

One project of the Fund is "Nature Mapping" (modeled on similar projects in Washington State and Oregon) that organizes people to document the presence, location, and condition of particular wildlife species across the region. In addition to many birds, the nature mappers have devoted particular days to identification and location of mammals. A favorite subject: the grand North American moose. On a single day in 2009, some fifty-seven individuals sighted ninety-five moose. This number represented a decrease in the visible moose population, because warmer-than-usual weather allowed moose to scatter into less prominent areas of the valley. Click here to see the map!

The impetus to count things that we deem significant has long been a preoccupation of scientific research, and the technical advances in mapping in recent years have given us sudden visions of the patterns of biological and human interactions that in the not-too-distant past were simply guesswork. Early accounts of wildlife in the American West, for example, frequently noted large mammals--moose, deer, elk, pronghorn--by the hundreds, if not thousands, and we are used to reading estimates of the millions of bison exterminated in the nineteenth century. But the literal pinpointing on a computerized map of individual representatives of a species rewards our curiosity with an image that would have been unthinkable before.

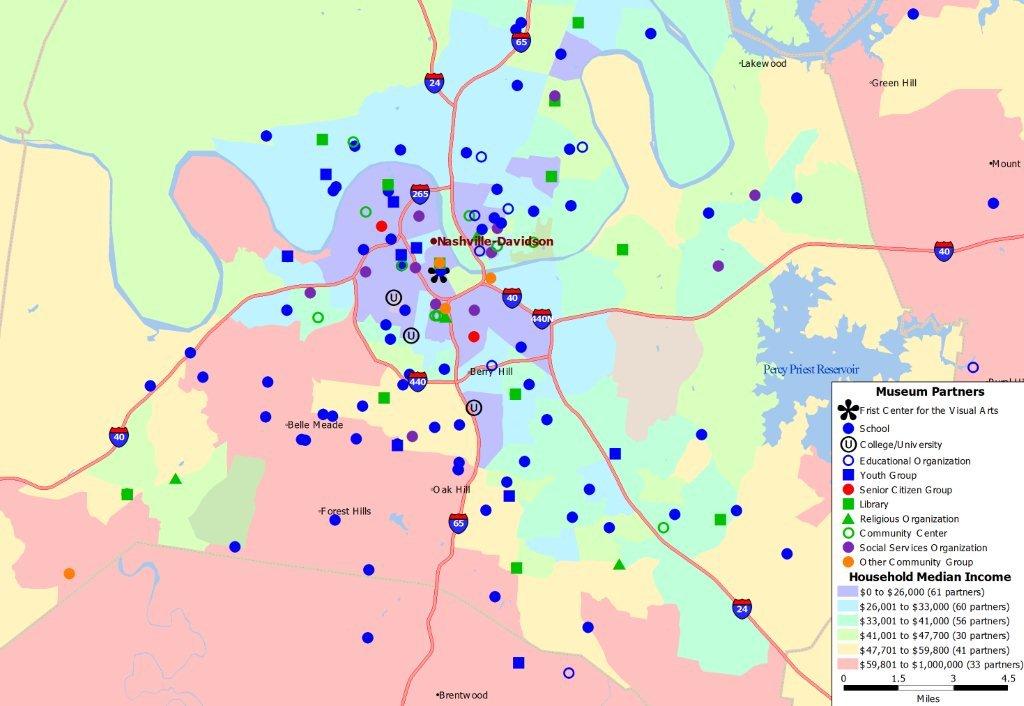

In like fashion, the Association of Art Museum Directors is also engaged in a mapping project, supported by the National Endowment for the Arts, to identify the many collaborations and resource exchanges that art museums create in their local communities. So far, the data supplied by over forty-five individual art museums has generated maps showing recipients and partners in educational services (schools, senior and community centers, libraries, etc.) and the locations of vendors to the museums (i.e., where the museum spends its money). An example:

Partners of Frist Center for the Arts, Nashville, TN

Here again, a bit of technology reveals patterns that we would have labored much longer to produce or not seen at all in earlier times. The assumption we make is that these patterned images will somehow cross over into human consciousness and cause us to change our behavior: taking better care of moose habitat, or insuring that museums receive adequate funding to continue to serve their communities.

Even armed with maps, these assumptions represent a challenge. Yet all of the technology points, finally, to the human necessity of personal contact, with people, art, and wildlife. Maps help us discover the flow of contacts about people, nature, and ideas--a constantly expanding universe.