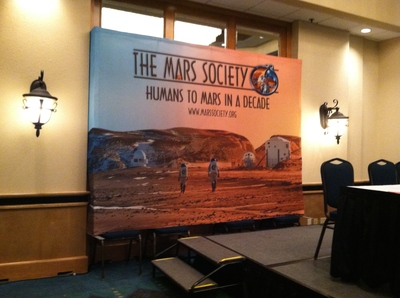

Last week 100 or more hopefuls looking for a way to Mars converged at the South Shore Harbor Resort in League City, Texas, just outside Houston, for the annual convention of the Mars Society: engineers working on intricate ways to get us there, "aspiring Martians" chatting up Mars One leader Bas Lansdorp, and fresh-faced university students designing take-alongs for Dennis Tito's Inspiration Mars, along with a few naysayers convinced it'll never happen, at least not in the next 10 years, as the big poster hanging in the aptly named "Crystal Ballroom" meeting room predicted.

Mars Society Convention: the setting, the goal

"Aspiring Martians" pose with Mars One CEO Bas Lansdorp (from left: Cody Don Reeder, Kenya Armbrister, Bas Lansdorp, Jan Millsapps)

As a first-time attendee, I spent my time trying to decipher the engineerese, looking at PowerPoint slides teeming with poorly arranged graphics and way too much text, and trying to read the mood inside the room.

I identified and observed two primary categories:

Those I'd call "the steadfast faithful" -- mostly engineers, and overwhelmingly "seasoned" white males -- made up the majority of the morning plenary speakers. They explained their propulsion systems, life-support systems, spacecraft designs, and landing gear and occasionally spun us beyond Mars with wild tales of lush exoplanets and space-warp systems designed to hyper-thrust us toward them. Most in this group seemed to be longtime Mars Society members and supporters of leader Robert Zubrin and his "Mars Direct" plan -- as presented in his opening remarks and detailed in his 1996 book A Case for Mars.

On the other hand, several dozen Mars One finalists, self-proclaimed "ordinary people," a gender-balanced group representing many ages and ethnicities, offered a sharp contrast to the engineering camp. I'd call these these "the untethered eager," individuals not committed to any party line but espousing a wide range of mental, psychological, logistical, and even financial approaches to Mars habitation. Lennart Lopin hopes his "Marscoins" will be the currency of choice on the red planet. Etsuko Shimabukuro wants to open the first sushi stand on Mars. (She'll grow the fish in the same hydroponic tanks used to grow vegetables.) Heidi Beemer will carve out underground "habs" to protect colonists from the radiation.

The Mars One group energized a sometimes-plodding conference whose headliners were mostly scientists talking to scientists, often replaying the past or criticizing the present or future. Some presenters teemed with negativity, mostly directed at anything and everything NASA, from diminished budgets to ill-advised asteroid lassoing (even though many presenters and attendees were affiliated with Johnson Space Center right down the road).

Former NASA head Michael Griffin was most critical in his assertion that the U.S. is no longer a spacefaring nation and that "our best stuff is in museums rather than in operation today." His idea, to reassemble the old tech and take another trip to the Moon, definitely put him at odds with the goal espoused by most of conference0goers. "It isn't necessary to reach Mars," he said.

Meanwhile the seven "aspiring Martians" who formed a Thursday-evening panel, following Bas Lansdorp's upbeat recital of his oft-told Mars One story, personified Mars One's commitment to diversity and also put fresh and enthusiastic human faces on the goal to colonize Mars. Even though half were scientists, it was the unstaid idealism they conveyed as they envisioned themselves living on Mars that most appealed to the audience.

"What's the craziest thing you'll do on Mars?" Lansdorp asked the panelists.

Among the answers: Turn up the music and dance; toss a Frisbee; joyride in a rover.

"Going to Mars is crazy enough," panelist Cody Reader deadpanned.

This seemed a conference at odds with itself. Getting humans to Mars is a huge scientific challenge, and the engineers are absolutely vital to its success, yet their detailed presentations almost entirely omitted the human factor so necessary in any successful Mars colonization. While the aspiring Martians personified the goal of getting humans to Mars, their massive enthusiasm for the Mars One mission sometimes edged toward cheerleading, placing their considerable collective scientific and technical knowledge in the backseat of any Mars-bound spaceship.

For four days I searched for a bridge between the scientific and the humanist, the steadfast and the eager. On the final day Howard and Laurel Hendrix, Cal-State professors and editors of the forthcoming Encyclopedia of Mars, provided the missing link, calling for a bridge between the sciences and the humanities, between the intellectual and the practical, a necessary connection for enabling humans to reach Mars.

The key, Howard Hendrix explained, lies within our educational system, which needs a big overhaul to merge science and tech with the arts and humanities. Discipline-specific instruction is shortsighted, incomplete, and perhaps even at odds with the requirements of any permanent Mars colonization, which will be far more than a scientific experiment. Humans on Mars represent an entirely new culture.

The 2008 Phoenix lander, he pointed out, carried a library to the red planet -- a digital collection of Mars-related vision, intellect, science, fact and fancy. But it took a finely tuned and engineered spacecraft to get it there.

Venturing from the refrigerated climate inside the convention hotel into hot and humid League City, I realized how easily we immerse ourselves in our own disciplines and envelop ourselves in our own values, and that exiting these self-imposed and limiting confines is key to understanding and propelling ourselves toward any future -- especially the one we humans envision on Mars.