(left) Four college students protest segregation at Woolworth lunch counter in Greensboro, N.C. in February 1960. (right) Picketers march in front of Kress store on Colorado Boulevard in Pasadena in 1960 in solidarity with Southern sit-ins.

On Monday, February 1, the Pasadena City Council will make a long anticipated decision about adopting a citywide minimum wage. That date happens to be the 55th anniversary of one of the most important events in American history -- the sit-in at the Woolworth's lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina.

The sit-in movement and the current movement for a $15/hour minimum wage and across the country are intertwined. Both movements quickly spread to Pasadena.

Late in the afternoon of February 1, 1960, four young black men -- Ezell Blair Jr., David Richmond, Franklin McCain, and Joseph McNeil, all students at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College in Greensboro -- visited the local Woolworth's store. They purchased school supplies and toothpaste, and then they sat down at the store's lunch counter and ordered coffee. "I'm sorry," said the waitress. "We don't serve Negroes here."

The four students refused to give up their seats until the store closed. The local media soon arrived and reported the sit-in protest on television and in the newspapers. Their actions inspired students at other colleges across the South to follow their example. By the end of March sit-ins had spread to 55 cities in 13 states. Many students, mostly black but also white, were arrested for trespassing, disorderly conduct, or disturbing the peace.

People of conscience around the country, including Pasadena, picketed outside local Woolworth and Kress five-and-dime stores in solidarity with the Southern sit-ins. The sit-in movement galvanized a new wave of civil rights protest, including the freedom rides, mass marches, and voter registration drives that eventually led Congress to enact the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Rev. Martin Luther King was proud of the civil rights movement's success in winning the passage of those important laws. But he realized that neither law did much to provide better jobs or housing for the large numbers of low-income African Americans in the cities and rural areas.

"What does it profit a man to be able to eat at an integrated lunch counter if he doesn't earn enough money to buy a hamburger and a cup of coffee?" King asked.

We often forget that the historic 1963 March on Washington -- where King delivered his famous "I Have a Dream" speech -- called on Congress not only to pass a civil rights bill but also to raise the minimum wage. In 1963, the minimum wage was $1.25 -- the equivalent of $9.18 in today's dollars. One of the march's specific demands was "a national minimum wage act that will give all Americans a decent standard of living." The March's manifesto pointed out that "anything less than $2.00 an hour fails to do this." A $2 minimum wage in 1963 would be $15.49 an hour today.

King observed: "Negroes are not the only poor in the nation. There are nearly twice as many white poor as Negro, and therefore the struggle against poverty is not involved solely with color or racial discrimination but with elementary economic justice." To achieve economic justice, King said, "there must be a better distribution of wealth within this country for all God's children."

"There is nothing but a lack of social vision to prevent us from paying an adequate wage to every American whether he [or she] is a hospital worker, laundry worker, maid, or day laborer," said King, who spoke in Pasadena in 1958, 1960, and 1965.

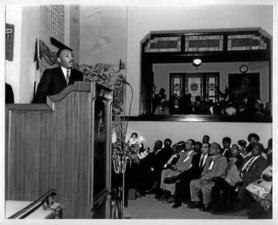

Martin Luther King delivers a sermon at Pasadena's Friendship Baptist Church in February 1960, shortly after the start of the Southern sit-in movement.

Like the civil rights movement of the 1960s, there is a growing movement in the United States today protesting the nation's widening economic inequality and persistent poverty. Congress hasn't raised the federal minimum wage of $7.25 since 2009. As a result, low-wage workers for fast-food chains and big box retailers, janitors, security guards, day laborers, and others have forged a grassroots movement to pressure their employers (like Walmart and McDonalds) to raise starting salaries and benefits. These workers and their allies have engaged in civil disobedience and strikes to galvanize public opinion.

They have also successfully pushed cities to adopt minimum wage laws that will pay families enough to meet basic needs. In response, a growing number of cities -- including Seattle, Kansas City, Chicago, and San Francisco, San Jose, Emeryville, Santa Monica, Mountain View, and other California cities -- have passed minimum wage laws tied to local living costs.

Just as the sit-in movement and civil rights protests spread across the country, the movement for a living wage has reached Pasadena, California -- an affluent city characterized by wide inequality and a large number of the working poor. Mayor Terry Tornek and most City Council members have declared their support for gradually raising the minimum wage to $15 by 2020, but the details of the actual ordinance are still up for debate. They are expected to vote on February 1 on a minimum wage.

In the 1960s, many Americans opposed the civil rights movement, arguing that their demands for racial justice were "too radical." Today, the Pasadena Chamber of Commerce and the California Restaurant Association oppose raising the minimum wage to $15 by 2020 on the specious argument that it will hurt the economy. There is no evidence for this, but the Chamber and its allies repeat this mantra nevertheless.

Pasadenans for a Livable Wage (PLW) --- a broad coalition of low-income workers, middle class professionals, clergy, nonprofit leaders, educators, unions, community and civic groups, and enlightened businesses - is urging Mayor Tornek and the City Council to adopt a plan that addresses this concern. PLW wants the law to include a provision to monitor the minimum wage's impact. It wants city staff to produce annual reports on sales tax revenue, employment, and business licenses comparing Pasadena data with comparable county and state date. If warning flags appear, further analysis will be conducted to determine causes. Temporary waivers may then be given for struggling industries while allowing the planned minimum age increases to go forward for other employers.

There are only few things that local governments can do to improve the lives of low-income families while simultaneously improving the local economy. Adopting a $15/hour-by-2020 minimum wage is one of them. A $15 per hour Pasadena minimum wage would inject over $230 million per year into the economy.

A recent public opinion poll found that 74% of Pasadena voters support the $15-by-2020 minimum wage plan with strong enforcement and an annual cost of living increase. Large majorities in every City Council district embraced the proposal. But the lobbyists from the Chamber of Commerce and the California Restaurant Association are pressuring the mayor and council members to weaken the proposed minimum wage law.

Dr. King's spirit will be in the City Council chambers in Pasadena City Hall on Monday, February 1, at 6 pm when the Mayor and City Council are expected to vote on the minimum wage law. Fifty-five years after the first historic sit-in, we need to remind our local elected officials that, as Dr. King said: "What does it profit a man to be able to eat at an integrated lunch counter if he doesn't earn enough money to buy a hamburger and a cup of coffee?"

Peter Dreier, a Pasadena resident, teaches Politics and chairs the Urban & Environmental Policy Department at Occidental College.