It's been a tough couple of months for the Massachusetts child welfare system.

Governor Deval Patrick and two child welfare officials are facing charges in U.S. District Court in a class action suit, Connor B. v. Patrick, which charges them with failing to protect the 7,500 foster kids in state custody from neglect and abuse.

The lawsuit, filed by the New York-based Children's Rights, charges that Massachusetts has one of the nation's highest rates of abuse of foster children in the country -- nearly four times the national standard -- and cites a U.S. Government Accountability Office study that found nearly 40 percent of foster children in Mass. were prescribed psychiatric medications, compared to slightly more than 10 percent of children outside of state custody.

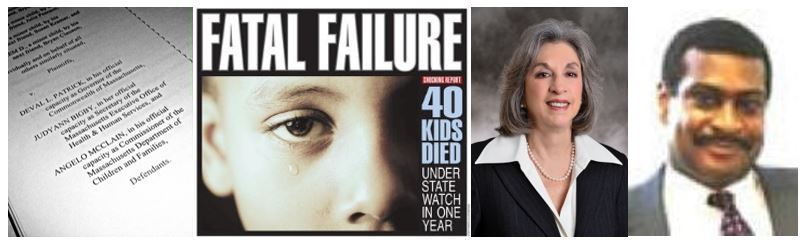

(L-R) Court Complaint; Boston Herald story; Children's Rights' Marcia Lowry; DCF's Angelo McClain

Photo credits: Lowry: Children's Rights McClain: Mass. DCF.

On March 7, Angelo McClain, commissioner of the Mass. Department of Children and Families, the state agency responsible for protecting the welfare of children and one of three defendants in the lawsuit, walked off the job just days after the plaintiff rested its case.

Prior to his departure, McClain had defended his department against the allegations in the suit saying he was concerned that resources being used to defend the case could be helping the children of Massachusetts. "It's distracting the agency from doing the work we need to do," McClain told the Boston Globe.

McClain's sudden resignation followed the departure of a second defendant in the case, Mass. Department of Health and Human Services Secretary JudyAnn Bigby, who left in December in the wake of a several scandals in her department.

The current trial focuses on the Mass. foster care system but it comes at a time when questions being raised in the state and nationally about the welfare of kids in Massachusetts, both in foster care and in other settings:

• The Judge Rotenberg Center in Canton, Mass. remains under a harsh public spotlight for its use of electro-shock with children for behavior modification, as a March 3 United Nations report joins the chorus of those calling the treatment of children there "torture."

• The U.S. Department of Education's Office of Civil Rights has opened up investigations following allegations by at least two parents in Lexington, MA that they were retaliated against after coming forward about the mistreatment of their kids in school. And an April 5 report of a survey by the town's special education parents group reveals that numerous parents reported being retaliated against by the school department after speaking up or advocating for their children.

• The 2012 annual report from the Massachusetts Child Advocate detailed 103 deaths among kids who were involved with state agencies between 2009 and 2011. These reports include that a 19-month-old baby died from "abusive head trauma while in the care of her family"; an "eight-year-old male died from intentional carbon monoxide poisoning while in the care of his family"; and a "seven-year-old male accidentally drowned in a bathtub while in the care of his family."

Marcia Lowry is the executive director of Children's Rights and an attorney in the Connor B. v. Patrick class action suit. Lowry has pioneered a body of law to protect children dependent on child welfare systems and served for more than 20 years as director of the Children's Rights Projects of the New York Civil Liberties Union and American Civil Liberties Union. Her work in New York City in the 1970s on behalf of foster kids was chronicled in Nina Bernstein's 2000 book The Lost Children of Wilder: The Epic Struggle to Change Foster Care. We spoke with Lowry about the federal suit and the state of foster care and child welfare in Massachusetts and nationally. Here are excerpts:

------------------------------------------------

What brought you to file the complaint? And how would you explain the basis of it?

We regularly keep track of data nationally of child welfare systems and from time to time we look at how child welfare systems compare with each other on certain national outcome measures that the federal government keeps.

We came to observe that Massachusetts was regularly scoring in the bottom portion of all of the states on a number of significant outcome measures. And frankly, that was a little surprising to us because Massachusetts has a good reputation for being a relatively progressive state and so we would have expected Massachusetts to do better.

So, when we observed this data we started checking further and did what we always do before we begin any litigation, which is we then conducted an investigation.

We did our investigation over a 12-month period and amassed a great deal of information. We talked with well over 100 people, probably closer to 200. And the more we talked to people, the more we learned the confirmation of what was underneath that data, and the fact that there have been very serious problems in the Massachusetts child welfare system for quite some time.

As is our usual practice at some point, we reached a point where we thought that the problems were sufficiently significant that the likelihood that they would be addressed by the state in a meaningful way was sufficiently small, and we concluded that a lawsuit would be beneficial for the children in the state.

How much of the problems that you are addressing [in the suit] are chronic in the system? And how much of them do you see as acute problems that have developed more recently?

One of the things that always catches our attention and that usually leads us to go on is the rate of maltreatment. The federal government ranks the states on the rate in which children who are in the state's foster care custody, that is, under the state's protection, are maltreated while they are in the state's custody. And Massachusetts ranks sixth worst. And it has been up around that for quite a number of years, and that's a very dramatic number because if a particular state can't keep its children safe, then that's a big clue to us that something is very wrong with the system.

Massachusetts' ranking near the bottom or ranking in the bottom fifth of states nationally -- and it varies from measure to measure -- has remained about the same. And in fact, we have lawsuits in most, although not all, of the bottom-ranking states in the country on the rate of maltreatment. As I say it's a pretty significant measure.

Then another very significant measure to us is the frequency with which children in state custody are moved from one place to another. It is often called "stability," but it doesn't take an advanced degree in psychology to know that if children are being moved from one place to another with any degree of frequency, that's harmful to children even if they are not getting physically hurt, it's psychologically devastating. Massachusetts was the 10th worst among the states on that measurement. That's pretty bad. So that was another major indicator to us that there were problems.

Then, there were several other factors that we thought added-up to the fact that children in the Commonwealth in the foster care system were being harmed at a very high rate particularly in comparison to other states.

Is there anything else you want to say about where Massachusetts falls with regard to child welfare?

Actually, there's one I find particularly troubling in addition to the ones I mentioned and that's although it is important for states to send children back to their families, children absolutely should not grow up in state custody in foster care. It's very important that children either get returned home to their families or if that's not possible, that they get adopted.

But in Massachusetts, about one in six children who are sent home, re-enter state foster care because they get abused or neglected again. And that's extraordinarily devastating to a child. It is bad enough to be abused or neglected by a parent in the first instance. And it is upsetting to a child, of course, to go into foster care, regardless. And then, to come out of foster care and go back home and get abused again is, I think, a very, very damaging thing and it indicates one of several forces at play; number one. the state is either making bad decisions and is not able to figure out which are the safe homes for a child to come back home, or the home is alright as long as the state provides services but the state's not providing the necessary services to keep the child safe.

What about caseload? It seems sort of self-obvious that there is a correlation between caseload and care, but how would you qualify it in terms of what goes on in Massachusetts and how serious that is?

Well clearly the [DCF caseworker] caseloads are too high. No matter how good the workers might be, if they've got too many cases, they can't do a good enough job for the kids because they don't have enough time. And that's clearly a problem in Massachusetts. And it has also been a problem for a while. Children can't be protected. Children are not, in fact, given the opportunity to get out of the system and into permanent homes. Workers don't have the time in planning for the child. Caseloads are a problem.

Massachusetts also counts their caseloads in a way that makes it very hard to figure out exactly how many children case workers are responsible for because the caseloads are counted by families. Most other systems count caseloads for children in foster care by children. Massachusetts counts caseloads by family.

Obviously, it makes a very big difference. If a worker has, say three families, that sounds pretty low, but if all of the kids are in foster care and they have six or seven kids in each family and particularly if they are in different places, which often happens, then obviously it's much, much higher. And so counting cases by families really masks the depth of the problem.

What do you feel you have been able to put before the court as far as the case? How would you describe the case that you have made so far?

We have presented a comprehensive picture of how the state system is working and also we have presented expert testimony, from experts who are knowledgeable themselves and who have examined the system and about what actually has happened to the children whom we represent as plaintiffs in the case. And the plaintiffs' stories are really appalling and they are the kinds of results one can expect from a system that doesn't have enough placements for children, that doesn't have enough supervision and doesn't have workers who have caseloads that are low enough so that they can do a job really paying attention to the children. So it has been a combination of very moving human stories, of a lot of data, a lot of statements from state officials about what they're doing or not doing. So I think we have presented a fairly clear picture about how the system functions and its impact on children.

How would you say this case fits into the national picture both in terms of the severity of what you're seen here and also strategically, it's one state, but how do you see this case fitting into the overall national picture of child welfare?

I think [Massachusetts] is an important state because it is in the Northeast. You know, all states have problems with resources, but there is sophistication in the state. There are really smart professionals in the state, and I found it interesting while we were investigating the case, and I find it interesting to this day, that a state like Massachusetts is performing as among the 10 worst states in the country on a lot of very important measures.

So we have cases in other states in the country and people would be less surprised. We have a lawsuit in Mississippi. We have a lawsuit in Georgia. We have a lawsuit in Tennessee.

I think that there is less surprise that we have lawsuits in states where there are real problems with social services but Massachusetts is certainly a center of learning and certainly is a state with many extremely well-qualified professionals and yet, the state still treats its children on some very important measures as a standard that's one of the worst in the country. So I think that's particularly interesting about the Massachusetts case.

Do you have any sense of why that is? Do you have any sense of how it is in the shadow of Harvard University and [Boston] Children's Hospital and all of these great institutions that you read in the Complaint about these really horrific stories? Do you have a sense of why or how this could happen in the state so rich with resources to care for children?

No, I don't. I never understand how states, or public officials and the public allow children to be as badly mistreated as they are so often are. And I think, the bottom line for all these places that mistreat children, is there is no public accountability and there clearly has been no public accountability in the Commonwealth for a long time. And there has been an absence of leadership from the top down in terms of looking at the data - and there is data - looking at the data and saying, "Why are we one of the 10 worst states in the country? And what are we going to do about it?" That has been going on for a while. Why? I couldn't begin to tell you. I can't read the minds of the politicians who run these systems, but it is certainly happening. I don't know whether the public simply doesn't know about it. But its public tax dollars and these are helpless citizens of the state and it is definitely happening.

The first named plaintiff got sexually abused in a state-run foster home. That's pretty awful. Another one of our kids was also sexually abused. So, unfortunately, sexual abuse of children is not uncommon in these child welfare systems and Massachusetts is not free of that.

So our view is, when really bad things are happening to children and that state knows about it and the state fails to correct it, the state is violating these children's Constitutional rights. And if they are violating Constitutional rights, they deserve to be held accountable in a federal court and that's what we're asking the federal Judge to do.