A recent study from the U.S. Department of Education showed that eighth-graders in the vast majority of states performed above the international average in math and science. The NAEP-TIMSS Linking Study also found that if Massachusetts and Vermont were their own countries, they would stand with the highest-achieving nations.

In many ways, the popular storyline that U.S. students get crushed in international comparisons is a distortion of the actual record. Truth is, our fourth- and eighth-graders consistently score above average, and do especially well in reading and science. Even our high school students are slightly above average in those subjects, falling below in math only.

Is "above average" good enough? Of course not! We need to keep up our efforts to do better, particularly at the high school level. But it's also important to keep in mind that even though we're not number one, our students are not failing. Wish we could say the same about American adults.

Another report was released in October that deserves the attention of every American because it points to issues related to literacy in the U.S. that extend beyond the reach of schools alone. The Paris-based Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) conducts various studies of economic and social institutions internationally. Stateside, they are perhaps best known for PISA which tests the knowledge and skills of 15-year-olds.

During 2011 and 2012, OECD administered an assessment of literacy and numeracy as part of its Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC). The test was given to a representative sample of adults aged 16-to-65 in 21 OECD member countries.

The difference between adult performance and that of our younger students couldn't be more striking: whereas the nation's fourth-graders are competitive with their international peers, American adults perform below the international average, and in the case of math, far below.

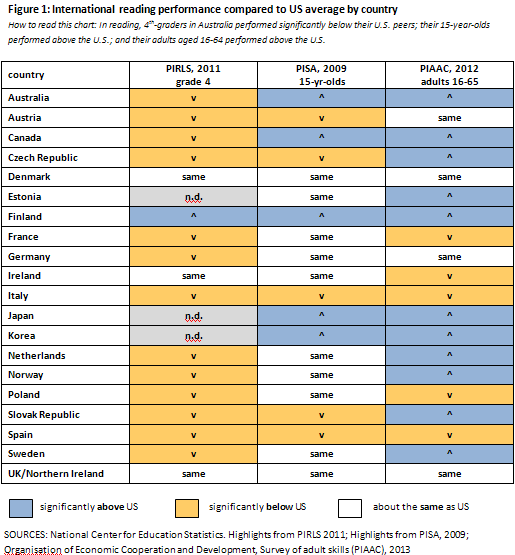

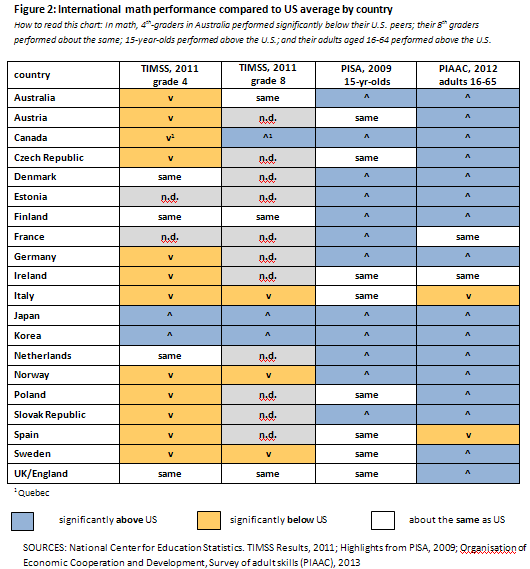

In Figures 1 and 2 (below), I arranged the OECD adult findings alongside the same countries' performance on international studies of elementary and secondary students' knowledge and skills. Each country's results are shown in relation to those of the U.S., meaning, a country is either below the U.S. average (gold), above the U.S. average (blue), or about the same as the U.S. (white). The relationships are all statistically significant.

Figure 1 looks at reading/literacy performance. The first column shows performance on PIRLS, the reading assessment of fourth-graders. Second is the already mentioned PISA which is taken by 15-year-olds. Finally, the PIAAC adult results are shown in the third column on the right. So in Australia, for example, fourth-graders performed below the U.S. average, and their 15-year-olds scored above the U.S. as did the adult population.

Clearly, fourth-graders in the U.S. do very well in reading (PIRLS, 2011) compared to their international peers. They performed significantly higher than 13 of the 17 countries according to PIRLS data, with only high-performing Finland outscoring us. While our relative performance drops among 15-year-olds -- five out of 21 countries outscored us -- our overall performance was still somewhat above the international average (PISA, 2009). In contrast, our adult population scored below the international average, and was outperformed by 11 participating countries (PIAAC, 2012).

The U.S. adult performance in math is even more troubling. Figure 2 shows math results for grade 4 and grade 8 (TIMSS, 2011), 15-year-olds (PISA, 2009) and adults (PIAAC, 2012).

U.S. fourth-graders once again hold their own. They performed significantly better than their peers in 12 out of the 19 countries with TIMSS data; only two countries, Japan and Korea, scored higher. U.S. adults, however, are significantly outperformed by their peers in 16 out of the 21 countries and surpass only Spain and Italy.

There are a lot of caveats and considerations in interpreting these results, and the study raises more questions than provides answers, beginning with:

- This is snapshot data, all of which was collected between 2009 and 2012. We need to look at longer trends to understand whether the high performance of fourth-graders today will translate into better adult outcomes later on, or if something else is happening with the adult population. One puzzle: the nation has produced steadily improving math scores for several decades as measured by NAEP and SAT. Yet the difference between our older (age 55-65) and younger adults (16-24) is modest and represents the lowest growth between generations in the study. We need to know why.

- The international assessments given to fourth- and eighth-graders (PIRLS and TIMSS) resemble tests typically taken by students and aligned with school curricula. Both PISA and PIAAC attempt to assess how well individuals apply their knowledge and skills in practical situations. Could these differences at least partially explain the performance gap between our younger students and adults?

- The overall poor performance of American adults has a perverse counter-image in those indicators the U.S. does lead in. The impact of social-economic class on literacy levels is greater here than in any other nation. We also lead in the relationship between literacy and wages, healthy living and civic participation, with those on the low end of the literacy scale having the least access.

There is clearly a role for schools in these findings. Schools need to build on the gains they are producing in elementary and middle school and double down on efforts to instruct high school students to higher levels. It would also serve schools well to examine instructional methods to make sure students learn concepts deeply and can apply them in unfamiliar situations -- something, by the way, the new Common Core standards strive to do.

But we are wrong to think that the schools can solve this alone. We also need to examine our social and economic policies that affect adult lives, such as the availability of continual learning, the impact of widening inequality, and the possible role our culture and media have on what we know and can do.

As the data show, schools are stepping up to the plate and as a result, our fourth- and eighth-graders are competitive against their international peers. For now, our kids have every right to tell us grown-ups to hit the books.