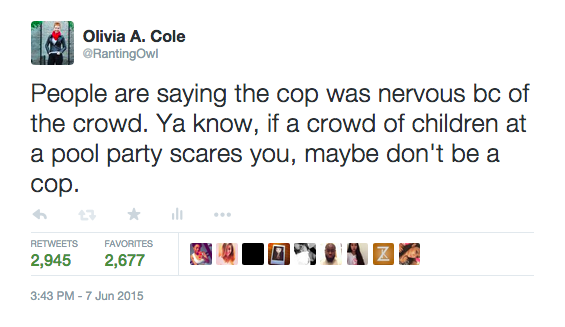

After seeing the footage of what occurred at a pool party in McKinney, Texas, and after seeing numerous attempts of newscasters and Twitter users alike to excuse the cop in question for his actions because he was "intimidated by the crowd," I tweeted this:

In all the discussion following the disgusting incident in which adult police officers attacked children, the concept of childhood requires special attention. Inevitable attempts will be made (have already been made) to turn the blame of these events onto the kids, and we must not lose sight of the fact that this was an incident in which black children were involved, and what the handling of these events means for black children everywhere.

Most of us recall the semantic struggle during George Zimmerman's trial. Trayvon Martin, 17 at the time of his slaying, was consistently referred to as a man by the media. The same went for Mike Brown, 18. The words we use when describing victims (as well as perpetrators) matter -- particularly when white killers are easily referred to as boys/teens by the media. It's such a subtle thing, but one that speaks volumes about the state of mind of those choosing these words, and the message they wish to impart. Trayvon Martin couldn't vote. Neither he nor Mike Brown could drink. One was in high school, one had just graduated, entering college in the fall. They were teenage boys. Yet many found it difficult to process their victimhood.

Entrenched in racist upbringing, Americans are uncomfortable with the idea of black innocence. In fact, studies show that white people consistently perceive black children as older and "less innocent." Tamir Rice was 12 years old, but was perceived as an adult when he was gunned down by Ohio police. Other stories about black children as young as six being taken out of school in handcuffs further expose an ugly truth: in a white supremacist society, black children are not children.

When you cease to see children as children, the world is no longer safe for that child. Most people are aware of some version of this. For example, when adult men see young girls as adults, the world is no longer safe for those girls. It's an attitude that most of us feel comfortable aligning ourselves with: the idea that a 30-year old man should not perceive a 13-year old girl as an adult. Her childhood, her youth, makes her in need of protection. Her behavior -- even when it mimics adult behavior in the way that children often do -- is a child's and therefore requires the treatment of a child; that is, careful observation and gentle correction when needed. This is how we treat children because, as children, it is understood that they are innocent.

Recently, I was tweeting about my experiences as a white girl in the public school system. An article called "Why Aren't Little Black Girls Allowed to Be Innocent?" crossed the timeline and led me on a tangent in which I reflected upon the way I was treated by teachers and administrators versus the way my black female peers were treated. At age 11 or 12, I was sexually abused by a staff member at my middle school, and as a result, my behavior exhibited all the common side effects of sex abuse: promiscuity, anger, problems with authority, depression. And although my school's resources were terrible, there were teachers and a school counselor that tried to help me. I was pulled into the counselor's office, I was kept after class, I was rarely given detention.

And that was the age when I first noticed the difference in the way I was treated versus the way the black girls were treated. Most of them were good students who obeyed the teachers. But many of them were like me: loud, angry, disrespectful. There were girls who (like me) wouldn't sit down, who seemed to carry something heavy on their shoulders that they dared the world to knock off.

These girls were kicked out of class, given detention, given suspensions; these girls had security called on them. These girls were expelled. These girls were never pulled into an office with a look of concern. These girls were never asked, "Are you okay?" These girls were both hypervisible but tragically, unforgivably invisible. These girls had all the symptoms of victims of abuse or neglect, but rather than concern and care, their behavior was met with punishment and disregard.

Since then, I've learned that the lack of response I noted in the faculty of my middle school is commonplace in America when it comes to black and brown children--with black children in general punished more severely than white children, and black girls specifically facing serious discrimination. Khadijah Costley White shared stories from her childhood in a piece for the Washington Post, in which she described the distress and pain of growing up black and female in school. She describes the punishment she received for her frustration, and it mirrors what I witnessed in my own schooling: black girls facing bias and neglect, who are then punished for their human response. What was interpreted as a cry for help from me was interpreted as "bad black girls" from my peers. It is in this way that black children are both hypervisible and invisible: in one way, the black girls at my school's behavior was hypervisible; subject to heavy policing and punishment, gossiped about by the faculty. But in another way, these girls were entirely invisible: the causes for their behavior going unexplored and unconsidered, their cries for help unheard.

This is how black children are dehumanized every day. When blackness is conditioned into the psyche of a society as inherently bad, there is no such thing as children -- only blackness and the "badness" that comes with it. It is this ideology that could lead adult white women in McKinney to allegedly pick a fight with a black teenage girl -- a child -- that would then lead to the police being summoned. It is this ideology that leads adult white men -- police officers -- to use the kind of force we've seen in the McKinney footage against black children. And it is this ideology that will lead many of you to watch the footage and still find black children to blame.

A white kid at the pool party -- the one who recorded the incident in McKinney, in fact -- said the following: "Everyone who was getting put on the ground was black, Mexican, Arabic. [The cop] didn't even look at me. It was kind of like I was invisible."

This is what it means to be white in America. To be visible for the good and invisible for the bad. We are on every TV screen, every magazine cover for our achievements, but when we riot after a basketball game or a Pumpkin Festival, we're slid quietly to the bottom of the deck, or gently sat by the side of the road and without cuffs after engaging in a shootout with police.

In the McKinney footage, you can hear black children screaming that they need to call their mothers. A 14-year old girl in a bathing suit is thrown on the ground, her face on pavement, and when two boys try to help her, a policeman draws his gun and points it in their faces. As you watch the footage, consider the study I cited above, in which it is shown that people (including cops) see black children as older and "less innocent" than whites. Let it really sink in.

If you find your mind wandering to different excuses that you might make -- "But were they trespassing? That one looks older. Why didn't they just obey? "-- stop yourself. Stop and look at yourself, because by doing that (even if you do it silently and in your own head), you are contributing to the dehumanization of black children. Before you start to say, "We need to teach kids to obey the police," think of what you are calling for. Think of the world you are asking children to create -- one in which they must blindly obey an unjust authority that has license to kill if they don't toe the line. One that tells them that they have no recourse when defending themselves from adult attackers. One that tells them that they must obey -- always obey -- or die.

There is a poem by Ai that I quote often, in which she writes:

"what can I say, except I've heard

the poor have no children, just small people."

This poem says something about the way the oppressed are perceived: sympathy gone, empathy gone. The gentleness we reserve for children, gone. The "small people" in the McKinney video are children. Where is your gentleness, America?