It's not just Iran. Getting news out of countries in the throes of political turmoil has always been dicey.

And getting the news out has often turned on using the most recent technology to thwart the authorities.

Recall during the Tiananmen protests in 1989 the exchanges of faxes between the Chinese students in Beijing and expatriate Chinese students in universities around the world. Those outside China faxed the students in Beijing daily summaries of Western news accounts; those in Beijing faxed out first-person accounts of what was happening on the ground. Or remember in 1996 when the Milosevic regime shut down the alternative Serbian radio station Radio B92, its programming stayed on-air because the BBC and Voice of America rebroadcast B92 Real Audio files downloaded via the Net.

And before either of those there was Vietnam.

In the early days of the war during the Kennedy administration, before the foreign press operated under the rules of the US forces, journalists could send their copy and photographs out of the country via the radio transmitter at the Saigon Post, telephone, and telegraph office, but they had to pass the South Vietnamese censors first.

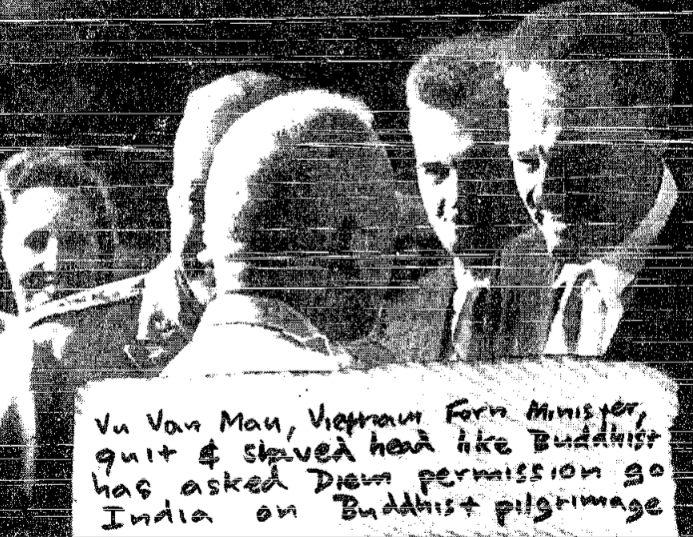

One of the tricks AP reporter and photographer Malcolm Browne repeatedly used to get past them was to "get an innocuous-looking picture ok'd... and then just the instant before the drum started to turn... stick something on top of it -- a short message saying what had actually happened that day... You could slap it on, stand with your back to the thing while it turned, and quickly rip it off the instant that it stopped." In August 1963, The New York Herald Tribune ran on its front page a photograph of Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge that had been approved by the censor -- but with a note from Browne still showing: saying that the Vietnamese foreign minister had just resigned.

A photograph printed on the front page of the Aug. 24, 1963 New York Herald Tribune of Amb. Henry Cabot Lodge (right) with a note pasted on top to circumvent the censor. The white horizontal scratches on the photo are from the radio transmission, which worked by scanning the image line by line. Observe that the written message would have easily fit within Twitter's 140-character limit. It's not just in the 21st century that essential news is sometimes communicated in short bites.

What's the point of the news getting out, in real time?

As we've seen this week in Iran, the free exchange of information is critical for those inside a country in turmoil as well as those on the outside. Those inside the country need to communicate with each other: to organize, to share information critical to staying safe. And they need to know what the world is saying. Is their story being told? Do they have the support of the global community?

Those outside the country need alternatives to the official reports of events -- and the more perspectives, the better, especially when there are few mainstream media able to cover what's happening.

That's the problem now in Iran. There are very few international journalists from mainstream media in the country -- although those who are there are among the very best international reporters in the business. Those on the print side include New York Times Executive Editor Bill Keller, Washington Post reporter Thomas Erdbrink and McClatchy reporter Warren Strobel, and among the broadcasters, there's BBC correspondent John Simpson, Channel 4's Lindsy Hilsum, ABC New correspondent Jim Sciutto and CNN's Christiane Amanpour.

Yet as good as they are, they aren't enough.

That's the value of today's 24/7 handheld, uplinked, connected technologies -- the Twitters, YouTubes, Facebooks, Flickrs and so on. The social networks help everyday people talk to each other and bear witness to the world.

Yes, their reports need to be checked and verified, aggregated and contextualized. But the outside world's chances for a fuller picture of what's going on in Iran, of the larger reality to be seen, is exponentially increased.

Through the new media technologies Iranians and the world stand a much better chance that the truth will come out.

-----

Note: The quote from Malcolm Browne, who ended his career as a NY Times reporter and editor, is from an interview I conducted with him for my book Shooting War: Photography and the American Experience of Combat. Browne was the one who alerted me to the photograph that appeared in the 1963 New York Herald Tribune. Browne's best known Vietnam War photograph was also taken in 1963 -- the famous image of the self-immolation of a Buddhist monk in protest against the Diem regime.

Please also take a look at a story at CNN.com: In Iran protest, online world is watching, acting