Amy Powell's book Depositions: Scenes from the Late Medieval Church and the Modern Museum came out in March from Zone Books / MIT Press. We asked her to say a little about the book's curious mix of past and present.

A good place to begin might be the Louvre Museum on March 8th, 1978 at 12:00 p.m., when a little known artist named Christopher D'Arcangelo performed what he called a "demonstration" by surreptitiously removing Thomas Gainsborough's Conversation in a Park from the wall and putting it on the floor.

This was an iconoclastic act, to be sure, but it was also the most natural thing in the world. After all, easel paintings are made to be taken down.

Louise Lawler, Nude, 1984. Photo: Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, NY

It happens all the time.

Louise Lawler, Pollock and Tureen, 1984. Photo: Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, NY

Easel paintings are made to be taken down so that they can be put up again -- somewhere else. Each time this happens, they're liable to end up in a situation totally different from the one in which they were last seen -- as different as the painter's studio and the Tremaines' dining room, where Louise Lawler finds a Pollock complementing the china.

Crucifix with Movable Arms, ca. 1515. Photo: © www.karlheinzfessl.com

Of course, getting moved around like this doesn't happen only to paintings. Many crucifixes that once belonged to churches now hang in front of the "neutral" white walls of museums, along with easel paintings and other things.

Crucifix with Movable Arms, ca. 1515. Photo: © www.karlheinzfessl.com

Though it's certainly not an easel painting, this crucifix is more like one than you might think. It was made in the early sixteenth century to reenact Christ's deposition and burial each year on Good Friday. Thanks to its hinged shoulder joints, its arms could be lowered to its sides after it had been removed from the cross. It was then ready to be "buried" in a sepulcher, where it remained until its resurrection on Easter Sunday.

Like easel paintings, crucifixes with movable arms like this one are made to be taken down... and to be put up again.

Rogier van der Weyden, Deposition from the Cross, ca. 1435. Photo: Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY

More familiar than these annual ritual re-enactments are representations of the deposition of Christ in paintings. The deposition is an interestingly self-reflexive subject for a painting. Insofar as Christ himself is an image -- the imago Dei (the image of God) -- a painting of his body being lowered from the cross is, among other things, an image of an image being deposed. A painting like Rogier van der Weyden's Deposition in the Prado Museum shows us, then, something about the bringing low of images -- including itself.

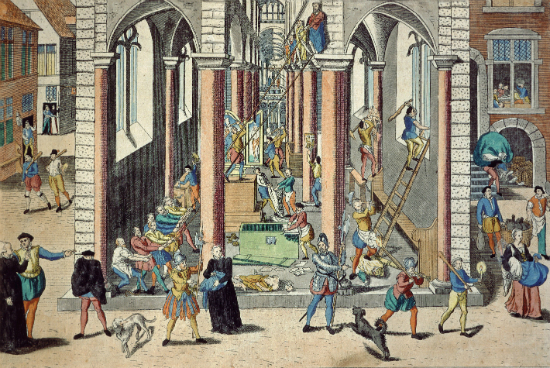

Franz Hogenberg, Iconoclasm, 16th century. Photo: Gianni Dagli Orti/ Art Resource, NY

Not so long after Rogier van der Weyden painted this scene, iconoclasts would perform very real acts of image deposition. When they didn't smash religious icons (including crucifixes with movable arms), the iconoclasts of the Protestant Reformation sometimes simply took them down.

My book is about these various scenes of image deposition and the parallels between them: from ritual burials of crucifixes, to paintings of the lowering of the imago Dei from the cross, to the Protestant purging of "idols," and finally the literal and metaphorical deposition of easel paintings in more recent times.

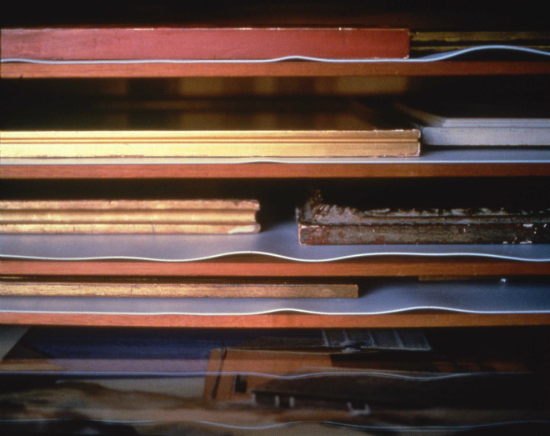

Louise Lawler, Pictures That May or May Not Go Together, 1997-98. Photo: Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, NY

It's also about the company that deposed images keep when they're put up again, far from where they were first seen. In museums, whether real or "imaginary" (as André Malraux calls the virtual collection of images that mechanical reproduction makes possible), old and new coexist as so many Pictures That May or May Not Go Together -- the title of Lawler's photograph of paintings "buried" in a museum storeroom.

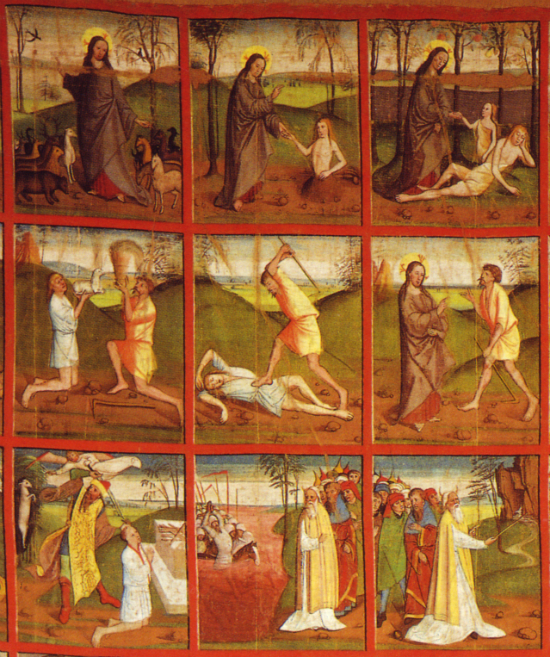

Haimburg Lenten Cloth, 1504. Photo: Heinz Ellersdorfer.

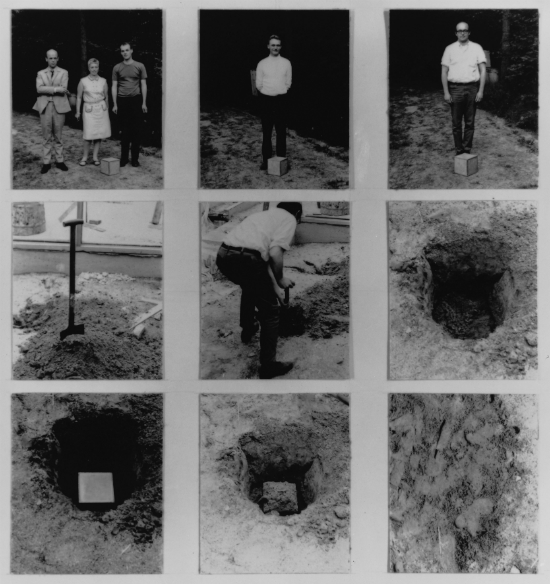

Sol LeWitt, Buried Cube Containing an Object of Importance But Little Value, 1968. Photo: @ 2012 LeWitt Estate /ARS, New York

Wandering through museums filled with works of art from different times and places, one sometimes notices formal resemblances between them. Art historians are taught to ignore these echoes -- for good reason: when it comes to such resemblances, historical difference usually outweighs any sameness. Sol LeWitt's photographic "contract" for his Buried Cube is more unlike than like this 500-year old Lenten cloth. But when we dismiss the resemblance between these two narrative grids as merely formal, we repress the fact that images, in general, tend to circulate well beyond their original contexts and, when they do, they routinely enter into all sorts of unlikely relations.

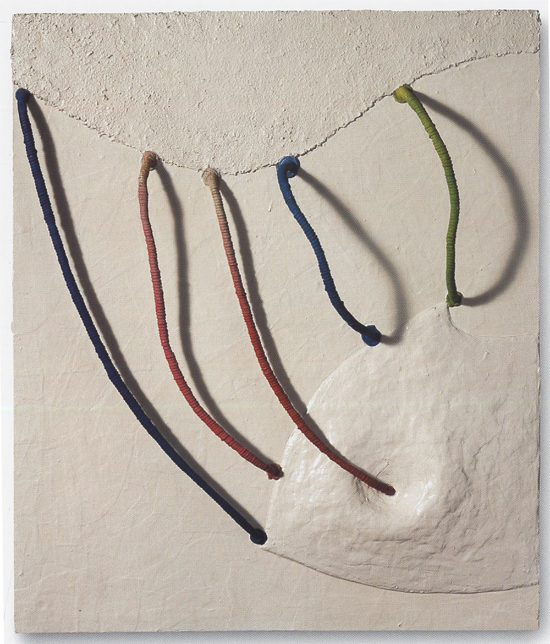

They may be faint, but if we simply ignore the formal echoes between these two rows of curved figures arrayed in relief against a flat background, we beg the question of the afterlife of images -- a question that Rogier's Deposition, in its self-reflexive way, already seems to pose.

What would it mean to take seriously formal resonances between objects as historically, materially, and conceptually far apart as these, without forgetting their differences? How might we think about their accidental similarities without resorting to notions of spiritual affinity? If we acknowledge that many works of art, from crucifixes with movable arms to easel paintings, are designed and destined to be taken down and to be put up again in the company of strangers, I think we have to at least ask ourselves these questions.