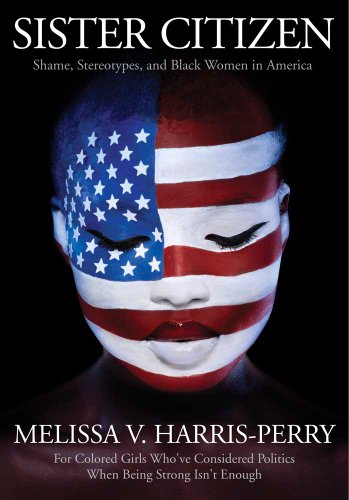

Tulane professor, MSNBC contributor, and all around amazing person Melissa Harris-Perry has a new book out - Sister Citizen: Shame, Stereotypes and Black Women in America. She came through D.C. yesterday, and I was lucky enough to watch her discussion at the Center for American Progress and see her in person at another event later in the day. (You really should watch the C.A.P. video. It's worth it to listen to her go in hilariously on The Help.) Overall, I'm incredibly impressed with Sister Citizen so far (I'm about a third of the way through). Cable news drives me bonkers, so until now, my exposure to Harris-Perry came mostly through Twitter and her writing for The Nation.

Harris-Perry's new book is concerned with how stereotypes surrounding black women affect their political beliefs. The book is interdisciplinary, in the best possible way. She uses literary analysis, cognitive psychology, and a host of other fields to explore how twisted perceptions of black women in turn twist their political beliefs. The book breaks these tropes into three general categories: the comforting Mammy, the lascivious Jezebel, and the angry Sapphire, with the idea of the stereotypical "strong black woman" manifesting in all three. At first glance, the "strong black woman" doesn't sound so bad. Who wouldn't want to be the woman who can handle everything herself, maybe with a little help from God? The problem is that being determined to handle everything yourself also makes you less inclined or even ashamed to ask for help, be it from other people or from your state; or more inclined to ask for less than what you deserve. Harris-Perry offered the example of the Tea Party -- a group of people who are quite loudly demanding what they think they deserve from their government, even if what they want, arguably, is for government to commit suicide. (What's that saying -- "you're only a libertarian until your house is on fire?")

The problem is further exacerbated by African Americans' long history of deploying what Harris-Perry calls "fictive kinship":

"The term fictive kinship refers to connections between members of a group who are unrelated by blood or marriage, but who nonetheless share reciprocal social or economic relationships. In this book, I draw on the deep tradition of black fictive kinship when I refer to black women as sisters. This imagined community of familial ties underscores a voluntary sense of shared identity... Fictive kinship makes the accomplishments of African Americans relevant to unrelated black individuals."

The entire month of February is all about fictive kinship. It's why we point to Harriet Tubman and Rosa Parks and Michelle Obama and Claire Huxtable. But the downside of fictive kinship, Harris-Perry notes, is that "if the success of unrelated fictive kin can make me feel proud, then the failures of unrelated fictive kin can make me feel ashamed." Not to beat a dead horse, but that sense of shame, again, can cause black women in particular to not ask for what they need, or less than they deserve. In this economic climate, no one is asking for increased funding for SNAP (food stamps), WIC (Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children), or Section 8 housing vouchers -- those things are the provenance of shameful women, women who are not strong enough to do it all. (In fact, Congress is STILL angling to cut funding for many of those programs.)

Harris-Perry also uses Hurricane Katrina, to great effect, to illustrate the dual problem of hypervisibility and invisibility for black women. She gives this example of this Economist cover. The woman is unidentified, suggesting that while black women have the ability to shame America (hypervisibility), that particular woman's individual voice goes unheard and unattributed (invisibility). Another example of the dichotomy she cited, and something that I as a fan of horrible reality TV can appreciate, was that of the Real Housewives. Leaving aside Real Housewives of Atlanta, Harris-Perry observed that the shenanigans of all the other Housewives do not provoke grand discussions about the state of white women. They're treated as individuals, not as representatives for all white women.

There is a lot to unpack in the book -- I haven't touched on her discussion of black faith as a revolutionary idea and rejection of the prosperity gospel, and the black church's role in transforming that into an often patriarchal and sometimes misogynist message. I haven't gone into the idea of the "crooked room," wherein one has to determine the true upright when everything in the room is tilted.

Anyone else out there reading along? There was a lot of nodding in the room at the event yesterday as she spoke. I'd be curious to hear what y'all think.