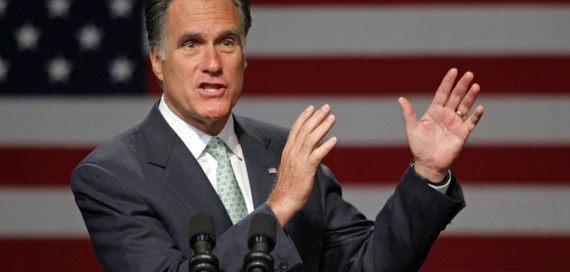

It is almost painful to hear Republican "establishment" leaders like Mitt Romney openly wish for a "brokered" or "contested" convention in 2016 to pick a party nominee for President of the United States. Romney has make clear how vehemently he dislikes Donald Trump, who has won a large plurality of the 2016 delegates so far in open primary and election contests. But there are very good reasons this country rejected the practice of "contested" nominating conventions half a century ago. And we kicked out the "bosses" and "brokers" too.

Bringing them back now will not solve Mr. Romney's problem, and could raise a whole host of new ones in the bargain.

- The Old Way

Few Americans are old enough to remember the last multi-ballot conventions, the Republican one in 1948 (three ballots) that nominated Thomas E. Dewey and the Democratic one in 1952 (also three ballots) that chose Adlai E. Stevenson - both of whom lost the presidency by large margins. Up until that point, multi-ballot conventions were the norm in America.

Over the years, Democrats have staged the longest contests, including the record 102 ballots to pick another loser, John W. Davis, in New York in 1924. Many fine president emerged from multi-ballot conventions, including Abraham Lincoln in 1860 (3 ballots) and Franklin Roosevelt in 1932 (4 ballots). Woodrow Wilson took 46 ballots to win his nomination in 1912.

The last truly successful "brokered convention" - where party elders literally met in a smoke-filed hotel room to break a deadlock and dictate the decision -- came almost a century ago in 1920. That year, Republicans met in Chicago with twelve competing candidates. Ohio Senator Warren G. Harding had trailed badly after the first eight ballots when the convention adjourned its first day of voting. But with no break in sight, Harding was invited into a hotel room late that night where he found a half-dozen party leaders around a table. They asked him if he had anything embarrassing in his past, to which Harding said "no."

The next morning, the votes quickly appeared to make him the nominee. Harding easily won the Presidency that November, but died in office shortly before a parade of scandals under the umbrella "Teapot Dome" erupted to stain his legacy.

- The breaking point, Chicago 1968

But times changed after 1920, and the real death-knell to boss-dictated Presidential nominations came in 1968, the most disastrous year for Democrats since the Civil War. Ever since, the very idea has become anathema.

Rage over the Vietnam War had split the Democratic Party in 1968 and forced President Lyndon Johnson to drop his re-election bid after an embarrassing second-place finish in that year's New Hampshire primary. Each on an anti-war platform, Senators Robert Kennedy (D-NY) and Eugene McCarthy (D-MN) fought a string of primary contests that spring, with Kennedy with the edge. President Johnson's Vice President, Hubert Humphrey, entered the race too after Johnson's recusal, but Humphrey refused to run in a single primary. Instead, he collected a king's ransom of delegates in closed state caucuses where party leaders act behind closed doors.

The assassination of Senator Kennedy in June after winning the California primary added to rising tempers and left his nearly 500 delegates uncommitted. In the confusion, party leaders led by Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley and Johnson White House aides cracked the whip on Humphrey's behalf.

By the time they reached Chicago, voter input had been brushed aside. Despite large majorities in the primaries backing peace candidates, the convention easily defeated a "peace plank" to the party platform and nominated Humphrey on the first ballot. The result: riots in the streets, fist fights in the convention hall, defeat in November, and years of intra-party hatreds.

The 1968 experience that caused both the Republican and Democratic parties to reform their rules and require all states henceforth to choose delegates through open primaries and caucuses, assuring voter control of the nominating process.

- A more likely model, 1880: Grant v. Blaine v. Sherman = Garfield

More typical of the old-fashioned multi-ballot type, and a more likely model for 2016 Republicans, was the 1880 Republican contest in Chicago, a 36-ballot extravaganza that I describe in my book Dark Horse: The Surprise Election and Political Murder of James A. Garfield. That convention featured a three-way contest with the "establishment" candidate, former president and Civil War hero Ulysses Grant seeking a third term, facing two main rivals: James Gillespie Blaine, a former House Speaker and Senator from Maine, and John Sherman of Ohio, the then-Secretary of the Treasury.

Grant had the most delegates, but not a majority. Both the other camps - Blaine and Sherman - were dead set against him. The result was stalemate.

From the start, party leaders tried to fix the outcome, but consistently failed. Grant's friends tried to stack the deck by proposing a "unit rule" that would silence dissidents within the larger delegation. But they succeeded only in embarrassing themselves. The proposed rule was defeated on the convention floor.

Once balloting started, the votes deadlocked. Over the first twenty exhausting ballots, the count barely changed. That night after adjourning, leaders again tried cut a deal. This time, it was the Blaine and Sherman managers who met in a hotel room to see if they could unite their two factions - representing a majority of delegates -- behind a single candidate. But they faced two problems. First was the candidates themselves. Neither Blaine nor Sherman saw any reason why he, and not the other, should bow out. Second, the leaders quickly recognized that they had no followers. Blaine delegates had no intention of switching, no matter what their leaders said. So they did nothing.

Finally, the next day, on the thirty-sixth ballot, the delegates took matters into their own hands and stampeded for a "dark horse," someone who had not been a candidate but nevertheless was well liked in the room. In this case, the country got lucky and the dark horse turned out to be James A. Garfield (attending the convention as a John Sherman manager), a decent and intelligent Congressional leader who reluctantly accepted and pulled together a narrow November victory .

- The lesson for Romney:

So if Mitt Romney or anyone else in today's Republican "establishment" thinks they can deny Donald Trump the nomination by using a "brokered" convention to force a better outcome, history is against them. Today, there are no credible "brokers" and no willing followers. Any sense among delegates that the game is being fixed would cause an explosion. And if the drama plays out honestly - with Trump, Cruz, Kasich and Rubio (if he's still in the race) each refusing to bow -- the odds on a surprise "dark horse" remain high.

And if anyone thinks that this convention, populated mostly by Cruz and Trump delegates, if forced to pick a "dark horse," would turn to a safe, moderate, establishment figure like Romney or House Speaker Paul Ryan, they should think again. They won't be the king-makers. Any 2016 "smoke filled room" more likely would contain the likes of Glen Beck or Sarah Palin.

There is only one way to pick a nominee for president under the modern system without risking chaos: Whoever wins the most delegates should win the contest. Anything else will look like a fix, and the public will not buy it.