Mexico's 2016 budget is currently under negotiation, with a deadline of November 15 for its approval. This is the first budget that is fully adapted to the collapse in oil prices that began in the summer of 2014 (the 2015 budget still benefitted from the finance ministry's annual oil price hedge) but there is more to the government's fiscal plans than simply next year's finances.

An analysis of the finance ministry's Criterios Generales de Política Económica 2016 (CGPE16), the guidelines for fiscal and macro policymaking into the medium term, show some worrying changes that mark a major reversal of the government's fiscal ambitions. While most discussion has focused on the scale of the cuts (not nearly as severe as feared) and the implementation of the so-called "Budget Zero" process of item-by-item justification of spending, the CGPE16's projections appear to severely compromise the administration's ambitious spending commitments over the remainder of the term in the absence of a plan B to raise further revenue.

What follows is an analysis of some of the key topics in the CGPE16 that seem to have slipped under the radar.

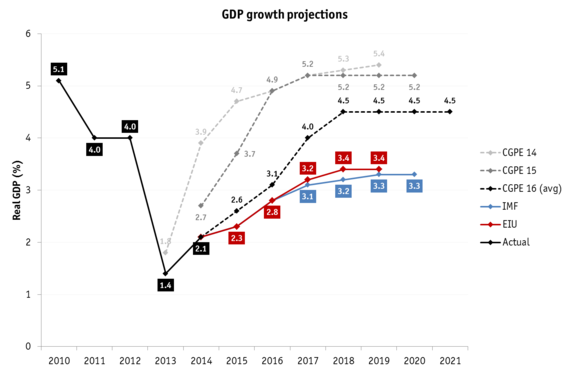

1) Growth projections have been tempered but remain unrealistic

Slowly but surely the government has adapted its GDP forecasts to a less buoyant reality, but one in which still assumes GDP potentially hitting the 5% mark as early as 2018. Contrary to previous years, the CGPE16 now establishes a forecast range of one percentage point from 2015 onward. According to the revised figures, GDP will rise to 2.6-3.6% in 2016, then 3.5-4.5% in 2017 after which it should settle at a new structural rate of 4-5% by 2021, the last year of the CGPE16's forecast period.

Fig. 1: Government estimates are still too optimistic

If this still looks far too optimistic, the last two CGPEs offered an even rosier projection of medium-term growth. The CGPE15 had growth of 4.9% as early as 2016, stabilizing at 5.2% from 2017 until 2020, and the CGPE14 had growth as high as 5.4% by 2019. To put this into historical context, the last time Mexico had two straight years of above 5% growth was in 1996-97 and this was due to the bounce-back from the earlier Tequila Crisis. Before that, it was in 1978-81, a period characterized by unprecedented fiscal profligacy (from oil revenues of all things) that subsequently led to a default in 1982 when oil prices crashed.

Non-official forecasts are far more sceptical than the government. At the Economist Intelligence Unit, we have Mexico's GDP growing at just 3.4% by 2019, the last year that we individually forecast. The IMF - in a rare instance of even greater pessimism than us - has Mexico at 3.3% in their last forecast year, 2020. These figures are no different than Mexico's existing potential growth rate which by general consensus stands at around 3-3.5%. The implicit assumption is that we will continue to expect some below-potential growth (say, 2.5-3%) which will be compensated by the 0.5-1 percentage point bonus from the reforms. In other words, rather than lifting growth to a higher structural level the benefit of the reforms will simply be to bring growth back to its pre-existing potential.

Strangely enough, the Mexican government appears overly gloomy about oil prices into the medium term: it still expects a price of only $61/barrel by 2021. The EIU has it at $85/barrel by 2019. How this low oil price forecast coincides with GDP growth of up to 5% is somewhat baffling.

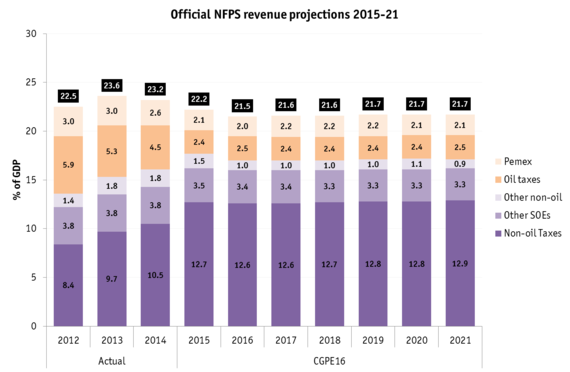

2) The fiscal reform is working but revenues have maxed out

Of all the structural reforms passed in 2013-14, the fiscal reform was the one that probably generated strongest objection not just by certain segments of the political class but also by businesses and average Mexicans. Businesses strongly opposed it not just because it closed various tax loopholes but because they were not consulted during its drafting. Individuals opposed it because it raised income taxes and slapped new taxes on various previously except items. The immediate impact of the reform, which was applied on January 1st, 2014, had consumer confidence plummeting to the lowest level since the global financial crisis, thereby prolonging the existing economic slowdown. A testament to the severity of the impact is the fact that confidence has yet to recover to pre-reform levels.

Despite this, the fiscal reform has been a revenue-raising success. Non-oil tax revenues have gone up from 9.7% of GDP in 2012 to 10.5% of GDP in 2014 and have risen by nearly a third year on year in the first half of 2015. The biggest gain has been through higher income tax receipts and the windfall from the IEPS special tax on gasoline (which acts as a subsidy when energy prices are high, and as a tax when they are low). Even excluding the IEPS, tax receipts are up almost 20% year on year in June and are therefore expected to come in at 12.7% of GDP in 2015 according to the CGPE16, possibly the highest level ever recorded in Mexico even though this is still paltry by OECD standards of around a third.

Fig. 2: Rise in tax intake will fail to compensate from fall in oil revenues

The problem is that this appears to be the extent of the fiscal reform's success. CGPE16 sees non-oil tax receipts dipping slightly in 2016-17 before climbing to 12.9% of GDP by 2021. Looking beyond just taxes, the overall revenue picture is even more dismal. Non-oil revenues will actually fall to 17.2% of GDP by 2021 and all revenues (both oil and non-oil) will also decline half a percentage point to 21.7% of GDP. This is the lowest level since 2006. Back in CGPE14, the estimate was for overall revenues to have reached 24.6% by 2019 which implies that the oil price crash has shaved off nearly 3 percentage points from the government's revenue projections - practically the same as it expected to raise from the fiscal reform! At least the government will claim that only one-fifth of the budget will rely on oil revenues by 2021 from around one-third before the oil price collapse; this being more representative of the state of oil prices rather than the magnitude and efficiency of non-oil revenue collection.

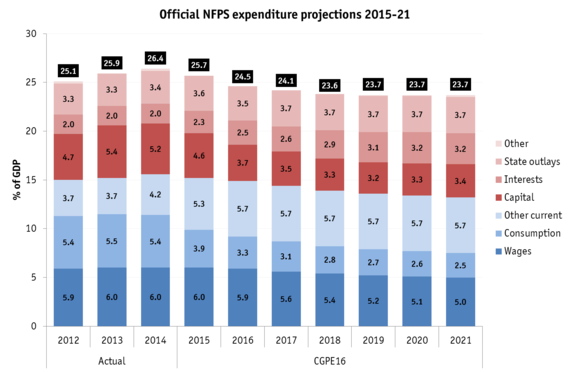

3) Capital spending will bear a disproportionate share of cuts

The CGPE16 also shows perhaps the most worrying trend that could impact longer term growth: a gradual decline in capital spending as a share of GDP. The current government achieved in 2014 the highest level of non-Pemex capital spending seen since the 1980s: 2.7% of GDP. Overall capital spending was also at recent highs of over 5.2% of GDP although it should be noted that an accounting change introduced in 2009 (which incorporates government investments in Pemex into the budget figures) makes comparisons to earlier years somewhat problematic. Still, the CGPE14 planned a strong rise in capital spending into the medium term. By 2019, non-Pemex capital spending was planned to be a robust 4.6% of GDP and overall capital spending 6.9% of GDP.

Fig. 3: Government now has capital spending shrinking rather than rising

CGPE16 now sees overall capital spending at less than half of that: just 3.4% of GDP in 2021. As such, of the total volume of cuts between 2015 and 2021, around a third will come from capital spending which is a disproportionate share since it currently accounts for only around one-sixth of the budget. Only public consumption of goods and services will fall by a greater amount during this time but this is justifiable given that current spending is where most fiscal slack can be trimmed. Public capital spending should ideally be ring-fenced to guarantee that needed investments in infrastructure materialize, and so that its contribution to overall GDP growth is positive - it has been negative since 2011.

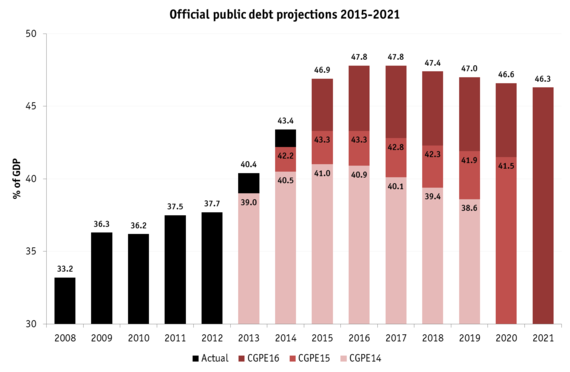

4) The debt keeps piling up

Lastly, this sub-standard fiscal performance will take its toll on the country's debt stock. Even using the widest definition of debt provided by the finance ministry, the Saldo Histórico de Requisitos Financieros del Sector Público (SHRFSP), Mexico's debt stock is still relatively low by today's middle- and upper-income standards: just 43.1% in 2014. This is quite a success if one recalls that Mexico along with numerous other Latin American economies had once been the global economy's fiscal basket-cases back in the 1980s (a title now held ignominiously by southern Europe).

The problem, however, is that in recent years the debt stock has been rising at a rather worrying pace despite the fact that the country is not in recession. Following the global financial crisis, the SHRFSP has remained broadly stable at an average of around 37% of GDP but then spiked to 40.4% of GDP in 2013, the first year of the Peña Nieto administration. An even bigger rise took place the following year, pushing the debt stock to 43.4% of GDP, a level not seen since 1990 when much of Mexico's fiscal crisis-era debt was restructured. The CGPE16 sees a further rise to 46.9% of GDP in 2015 (admittedly, exchange rate depreciation will contribute to this) and 47.8% of GDP in 2016-17 after which it should begin falling steadily.

Fig. 4: Actual rise is debt has overshot projections

The actual SHRFSP in 2013 and 2014 has in both cases widely overshot the CGPE's estimates which seems to suggest that its projections for 2016-21 are excessively benign as well. Furthermore, the view that the deficit will peak at 2016 appears even more unrealistic considering that it still envisages financing needs equivalent to 3.5% of GDP that year - not that much lower than in 2015 - and 3% in 2017. These will also likely come with a higher price tag given the expected rise in global interest rates over the next few years. Since debt-to-GDP projections are by definition tied to growth, the government's fanciful estimates for GDP performance are likely the reason why we're led to believe that the debt stock will begin to shrink from 2017 onward. If, however, the EIU and the IMF and the rest of the "pessimists" are right, growth of just over 3% in the context of a higher interest rate environment will not be enough to bring the debt stock down anytime soon.

Conclusion: Mexico's (Fiscal) Moment lost

Politically, the ability of the government to make radical changes to fiscal policy over the remainder of the term is constrained by its pledge not to raise taxes or impose new ones (this is the so-called "fiscal pact" agreed with the business sector back in 2014) as well as a more hostile opposition. There have been calls to revisit the proposal to impose VAT on food and medicine as a means to raise revenue since it would be one of the few measures to shift some of the fiscal burden on informal workers who otherwise underpay. But this would be a counterproductive policy from a consumer demand perspective and would derail any possibility of economic recovery in the short-term particularly if it happens when domestic demand is still fragile. It would also carry a significant political cost into the 2018 elections.

More worrying is that behind the veneer of responsible fiscal management and a commitment to austerity, the CGPE16 reveals a medium-term outlook that is devoid of ambition and that has seemingly swept away the grand plans that underpinned many of its commitments earlier in the term: the massive infrastructure projects (most of which, aside from the new Mexico City airport, have been shelved), the move towards universal social security, the funding for it numerous social "crusades", and the reduced reliance on oil thanks to more effective taxation. All of these require greater resources than the Mexican state will be capable of generating. If there's anything to conclude from the CGPE16's hefty 157 pages is that Mexico's (Fiscal) Moment, brought on by last year's unpopular but necessary reform, is all but over.

Follow the author at @raguileramx