This article courtesy of Miami New Times.

After locals were stung by the revelation that Miami leaders have known for two years that toxic ash is poisoning the Coconut Grove neighborhood surrounding its long-closed "Old Smokey" trash incinerator, city officials wasted little time last week confronting the latest environmental crisis.

Just four days after learning that soil tests in nearby Blanche Park turned up traces of dioxins, arsenic, barium, lead, and other deadly contaminants -- presumably from deposits of incinerator ash -- City of Miami crews swooped in with an assuring show of force, carting away truckloads of toxic soil and paving the excavated area with a foot of asphalt.

Commissioner Marc Sarnoff -- who, as fate would have it, lives across the street from the tiny strip of leafy suburban green space -- held vigil, pledging to neighbors and TV cameras that city workers were doing everything possible to guarantee the health and safety of residents, a message he repeated a week later at a tense, city-sponsored community gathering. Testing, he declared, would continue.

But far from the media spotlight and the glare of embarrassed city officials, toxic cleanup at four other city-owned properties is far less of a priority. There has been virtually no community input and little public awareness of the dangers that contaminated soils pose. Two of those properties are anonymous plots of grass with few visitors, but the other two are within high-volume recreational parks that serve a mostly low-to-middle-income population and where unsuspecting users of all ages and interests might be treading on ground unfit for human contact.

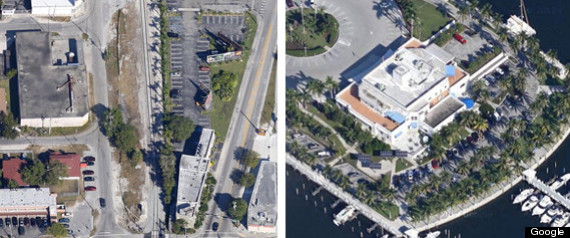

Four miles up the road from the toxic ground zero of Coconut Grove, in the shadow of the Dolphin Expressway on NW 11th Street near 22nd Avenue, sits Fern Isle Park, a narrow swath of ball fields, picnic pavilions, and the grassed-over remains of an illegal dump used for years by City of Miami work crews.

In 2001, county environmental regulators busted the city, issued a cease-and-desist order to stop the dumping, and demanded a clean-up plan, including lab tests to measure the toxicity of contaminated soil and groundwater. But according to reams of public records from the case uncovered by New Times, city officials refused to close the dump, arguing they would limit deposits to yard waste and what they considered other "clean" debris.

In time, they relented and shut down the dump, but records show officials routinely disregarded county demands to clean up and test the site, which abuts the south shore of a tributary to the Miami River. Not until 2005 did dumping cease entirely. The site was quickly cleared, and soil and water tests were completed. The results were alarming: PCBs, arsenic, cadmium, ammonia, and petroleum-based pollutants in the soil and groundwater.

A year later, at the request of Miami-Dade's Department of Environmental Resources Management (DERM), which has enforcement powers in pollution cases across the county, the city removed a layer of contaminated soil and installed monitoring wells to test groundwater routinely. But when subsequent tests revealed toxic substances remained, DERM asked that the site be covered in a two-foot layer of clean fill, effectively burying the contaminants.

The city, it seems, simply refused. In a dizzying exchange of emails, phone calls, and letters over the past seven years, county regulators prodded city officials to cap the site. "I would ask that you make one more attempt to bring these critical matters to the attention of the appropriate personnel, and please copy me on the correspondence," DERM code enforcement officer John D. Andersen wrote in a terse July 2012 email to the City of Miami's environmental compliance officer, Harry James. "If we can not get key people within the City onboard with us and committed to moving forward with these environmental concerns, within the next few weeks, we will have to regroup on the County-side and see how our management wants to proceed."

The threat did little good. Two and a half weeks later, city officials finally responded, but only with another request to extend their deadline for submitting their long-awaited clean-up plan. DERM approved the extension, but the plan never arrived, records show.

This past April, results of yet another soil and water test confirmed that contaminants remained. A month later, county regulators issued their most recent directive -- addressed by certified letter to City of Miami Manager Johnny Martinez -- demanding the city cap the site, install more monitoring wells, and submit an updated soil analysis within 60 days. That deadline passed July 15 with, predictably, no response from city officials.

The case came to light this past spring when a graduate student at the University of Miami School of Law's Center for Ethics and Public Service, 24-year-old Zach Lipshultz, was helping residents prepare a legal challenge to a trolley garage under construction in their West Grove neighborhood.

Why, he wondered, did the city-backed garage plan include a provision -- negotiated by Sarnoff and other city officials -- for a $200,000 gift from the developer for installation of artificial turf on an athletic field six blocks away? A public records request uncovered a shocking secret: Two years earlier, the land surrounding Old Smokey -- which lies adjacent to the athletic field -- tested positive for arsenic, lead, cadmium, and a host of other toxic substances.

Digging deeper, Lipshultz, a graduate of Coconut Grove's Ransom Everglades School and later a standout soccer player at Oberlin College in Ohio, uncovered references to other contaminated city-owned properties, including Fern Isle Park. In each case, it appeared, residents were never informed.

Indeed, a recent visit to Fern Isle Park revealed no efforts to warn visitors of toxic soil -- no signs, no fenced-off areas. Park manager Eduardo Quintana, a five-year veteran of the facility, said he's never been told of any contamination, past or present. "Can't say I've ever heard of any dump around here," he shrugged. "But look around if you want."

The affected site -- identified through county records -- sits at the southwest end of the park, away from the bustle of little-league games and toddlers on swing sets, but perhaps a draw to anyone looking for a quiet spot to picnic.

Sure enough, under the shade of a banyan tree on the shaggy mat of lawn lay remnants of a recent meal -- paper napkins, plastic utensils, a chip bag, a gnawed chicken bone. A soccer ball hid in the sprawling roots of the tree. A few feet away, a 55-gallon steel drum rested on its side -- the only major blemish on the sliver of lawn.

Meanwhile, across the park, two teams of 7-years-olds battled on the diamond in what appeared to be an endless game of hits and errors and furious coaches cajoling players to run faster or throw the ball harder. With his nephew planted in the outfield, 34-year-old Luis, who offered no last name, donned earphones and jogged slow laps of the park's perimeter, around the parking lots, ball fields, basketball courts, and finally the spit of land once used as a dump.

Had he any idea of the ground's toxicity? Panting and perplexed, he simply shrugged and continued his run, with the steel drum a pivot point to begin a new lap.

(County records indicate the drum has been at the site for years. It contains purged water from a monitoring well, is likely toxic, and should be disposed of with care.)

Fern Isle is not the only City of Miami park with a tainted history of contamination. On the west bank of the Miami River near the city's urban core is the hodge-podge of recreational buildings, outdoor pool, basketball courts, terraced courtyard, concrete paths, and landscaped picnic space known as José Martí Park. According to county records, soil tests in August 2002 turned up dangerous levels of arsenic and other toxic materials -- likely the detritus of decades of boat building and repair on nearby properties.

Months later, the city hauled away 206 tons of tainted soil from the park -- which stretches along SW Fourth Avenue between Second and Sixth streets -- but further tests revealed arsenic levels still above the allowable threshold for human exposure. Pressed repeatedly by county regulators to clean up or cap the contamination, city officials believed a new community center constructed in 2007 on the south end of the site would effectively pave over suspect areas.

But the building's footprint was too small, and later tests found more arsenic, leaving county regulators, records show, concerned by the slow pace of remediation. In a letter dated March 2008, DERM reminded the city that its deadline for submitting an updated engineering control plan for the site was more than a year past due, but granted an additional 60 days to comply. The city ignored the request and finally responded -- with nothing more than a renewed promise to provide a written plan -- a full year later.

In the years since, records depict county officials as persistent yet eternally patient with the city over the pace of cleanup at José Martí Park.

This past spring, amid a renewed push by county regulators to force the city to comply with pollution-control directives in this and other cases, City of Miami Parks & Recreation director Juan Pascual penned a letter to DERM blaming "staff turnover" for the eight-year delay in responding to the lingering 2005 demand for a new written plan of action. After his apologies, Pascual's letter proposed, finally, a plan to essentially to do nothing, because the park areas with positive arsenic readings, he asserted, are either off-limits to all but maintenance crews (who presumably know what to avoid) or, at the very least, are not easily accessible to park visitors.

DERM officials responded in a July 2 letter, agreeing to consider the plan, but only if it was presented in the form of a detailed proposal with monitoring guidelines, testing schedules, and other related control measures. The letter also demanded that six inches of mulch be spread over a contaminated area "where access is unimpeded by fencing." The city was given a September 2 deadline to submit the detailed plan. But it never arrived, nor has any other response.

In any event, the do-nothing plan might need some work. On a recent morning at the park, the contaminated areas were not marked, and maintenance workers expressed no awareness of possible exposure risks -- to visitors or to themselves. "Never heard of that," snapped one worker when asked to point out the toxic hot spots. Nor could he recall the prescribed mulch layering. A park supervisor -- four years on the job (she asked that her name not be used) -- responded to similar queries with folded arms and raised eyebrows. "You kiddin' me?"

Park visitors expressed similar surprise. "Arsenic. That's bad, right?" asked Yoselin (who declined to provide her last name) while her two children, ages 3 and 4, wandered the playground. Assured that it is indeed bad, she nodded toward the kids. "What if they were to, like, get it on them?"

As she pondered the prospect, six 20-somethings -- each holding a red plastic Solo cup, the guys wearing fedoras, the women in skirts and heels, all looking as if they just exited a taxi after a night on South Beach -- weaved through one another toward the play area. "Hey, we're looking for the yacht!" said one of the women, pressing a cup to her lips.

"No yachts 'round here," sniffed Yoselin.

Undeterred, the group continued its quest, underneath the span of I-95 that rises four stories above the park, around the gym and community center, and then back, following signs for the Miami River Greenway, which extends briefly here along the waterfront.

As they reached the park's north end, their search fizzled at the walls of a seafood packing plant. They gazed up and down the river. Their yacht was nowhere in sight. If the city's low-budget remediation plan for José Martí Park rests on its ability to control and monitor visitor access to toxic sites, nobody told this blundering bunch.

Neither Pascual nor City of Miami environment compliance coordinator Harry James responded to detailed requests for comment. But according to notes of a 2012 meeting between city and county officials, James -- the point man for the city's environmental concerns -- blamed "tight budgets" for the city's inability to resolve cases dating back more than a decade.

DERM could sue for failure to comply with county environmental laws in a timely manner, but it appears unwilling to apply the tough-love tactic. The files are filled with letters, year after year, ending with the same hollow threat: "Further failure to achieve the required compliance at the subject site shall result in additional enforcement action by this Department."

And the game goes on. Asked to describe the city's responsiveness in these two cases, which have dragged on for 12 and 11 years, respectively, DERM's longtime environmental chief, Wilbur Mayorga, cleared his throat before responding: "Let's just say they are not presently in compliance with regard to the cases we've discussed."

Lipshultz, the law student who uncovered the whole thing, is less diplomatic. He blasts the city for moving at a snail's pace despite the potential health risks. But he also takes county officials to task for what he describes as a kind of bureaucratic nodding and winking that fuels this regulatory dysfunction.

Only after the outcry following the Old Smokey revelations, he says, did the county and city agree to a far wider and more thorough testing program, which led to the Blanche Park closure. "Keeping things quiet is far less expensive," Lipshultz suggests. "But public pressure changes everything."

And the lack of public pressure might explain why the city is noncompliant in two other drawn-out pollution-control cases. Thirteen years after discovering soil tainted from an old underground oil storage facility on a city-owned swale along NE 55th Street near the corner of Fourth Avenue, DERM officials are still asking the city how and when it plans to clean up the mess. The deadline for the most recent compliance demand -- a report detailing completed soil excavation, disposal, and subsequent test results -- passed last Friday. The site, outside the Dixie Transport warehouse and across the street from Dr. Jacobsen's Weight Loss Clinic, is covered in grass, save a small splotch of soggy soil where turf seems disinclined to sprout.

A similar contamination, and perhaps a daily reminder of their costly remediation backlog, lies closer to home for Sarnoff and other city leaders under scrutiny for the handling of the Old Smokey cleanup: The soil beneath a small triangular wedge of waterfront land just outside Miami City Hall in Coconut Grove's Dinner Key is tainted with arsenic and an array of chemicals associated with petroleum.

To any visitor, the sloping patch of grass offers a stunning view of the Grove's working waterfront and across Biscayne Bay to the downtown Miami skyline. The only sign of trouble is a small pipe -- the head of a monitoring well -- protruding from the ground.

Environmental engineers suspect leaking storage tanks that serviced the flying boats that made the area a major hub for commercial air traffic in the 1930s. It is a relatively new discovery, dating back four years, when workers encountered suspicious-looking soil while excavating the area to install a storm drain. Some soil has been removed, but more must come out. And after the city missed an August deadline for detailing its long-awaited clean-up plans, county officials and local residents can only guess what happens next.

To be sure, city and county officials are far more focused these days on Old Smokey and the off-the-charts contamination at Blanche Park.

During last week's community meeting in the West Grove's Elizabeth Virrick Park, the officials, including DERM's chief, Mayorga, presented the expedited results of soil testing at 51 new sites within a one-mile radius of the incinerator, which closed in 1970. Contamination levels, he said, were low and generally consistent with other sites throughout Miami-Dade.

But there was one exception: arsenic, which appeared at elevated levels in about a quarter of the samples. Arsenic has been widely linked to a number of cancers, including one of the most deadly forms, pancreatic.

Mayorga downplayed the finding, explaining that arsenic, in fact, is often found naturally in the environment. But what he did not say is this: A little-known study published this past March by researchers at the University of Miami School of Medicine showed rates of pancreatic cancer in and around Coconut Grove were statistically higher than they should be -- what epidemiologists call a cancer cluster.

The likely cause of this cluster, the researchers concluded, is drinking water, possibly from private wells, contaminated with arsenic.

Get more from Miami New Times.