By Christopher Rosacker

The church where Greek Orthodox Ft. Makarios Makarios will hold services in the Arabian Gulf state of Qatar hasn't been built yet. Right now, it is a construction site just poking out of the sand, just a mile south of the Qatari capital of Doha.

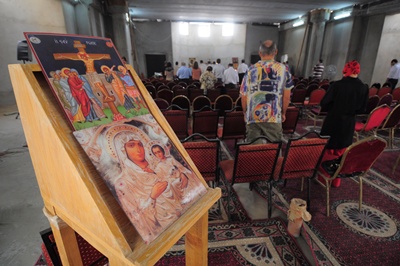

Arriving there one early Friday morning for liturgy, he walks through the site, past sand piles and unused two-by-fours, to a cement basement entrance. By 10:30 am, 60 members have seated themselves inside, among mismatched rows for a two-hour service.

Its resemblance to a bunker is coincidental, but it is the only place in Qatar where Christians can safely pray. "After a long time, we are getting the opportunity to have our own place," Makarios said.

The estimated 175,000 Christians in Qatar are cautiously building the foundation to practice their faith within this conservative country in the Muslim world. But while they move forward to that goal, many Christians in Egypt say they are trying to hang on to the freedoms they have long enjoyed.

U.S. President Barack Obama came to Cairo in June to address the Muslim world, and in his speech he said the region suffers from "a disturbing tendency to measure one's own faith by the rejection of another's," and referred to Egypt's Coptic Christians, urging that "the richness of religious diversity must be upheld."

With more than 80 million Egyptians, the CIA World Factbook reports 10 percent are Christian. Copts represent 90 percent of all of Egypt's Christians.

The heart of Coptic Cairo is home to the city's oldest mosque, synagogue and church. It is where Moses is said to have rescued from the Nile, and where the Holy Family rested during a journey.

Unlike Qatar, Christians have worshiped in several ornate churches there for centuries. But in recent times, like the Qatari Christians, the Copts have adopted a bunker mentality, as extremists have attacked the community across the country.

A few months ago, a crude car bomb was set off outside a popular church for pilgrims in Cairo where the apparition of the Holy Mary was witnessed. Outside the churches in Coptic Cairo, access is now restricted by police checkpoints and roadblocks.

Adding to tensions was a controversial decision in April by Egypt's government to slaughter the country's entire pig population to prevent the H1N1 flu virus from spreading in the country (that didn't work). Egypt's pig farmers are all Christian, and they interpreted the decision as an attack against them because of their faith.

"The government of Egypt had planned since 2006 to relocate the pig population," said Nadia El Awady, of the World Federation of Science Journalists, "and used the crisis to get rid of the pigs."

Egyptian Copts cite other examples of discrimination, such as employment signs that read "Muslims Only." In turn, many Copts bear tattooed crosses on their wrists and on necklaces to identify themselves to one another.

"There's generally a feeling that there's some places we can't go, and some things we can't talk about with certain friends," said Victor, a Copt business owner in Cairo.

It partly is an issue of perception. According to a recent study by C1 World Dialogue Foundation, an interfaith group that includes former British Prime Minister Tony Blair, 45 percent of Egyptians look unfavorably upon Christians.

"We need profound change," said H.E. Ali Gomaa the Grand Mufti of Egypt, and co-chair of the foundation. "To move religious discourse from aggressive and negative attitudes towards other religions, to the spirit of tolerance and co-existence."

In Qatar, tensions aren't aired publicly, partly because most Christians keep concerns to themselves, worried that speaking out will result in their deportation.

Much of their worship is also private; many choose to pray in small groups at home. At the church complex near Doha, no crosses will be visible, as it is forbidden for non-Muslim religious symbols to be displayed in Qatar. Parish leaders also advised congregants not to wear crosses around their necks or hang them on rear-view mirrors.

"How the people receive the Christians are different (from the government)," said Patrick Manabat, also a Philippine expatriate Catholic. "Some accept us, others do not."

For Egypt's Christians, they say their futures will be closely tied to the fate of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, whose son Gamal is expected to succeed him.

Many Copts said they viewed Mubarak's 28-year presidency under martial law as a godsend and attribute their freedoms to his reign. As Mubarak and his regime gained support from the U.S., churches sprang up.

But the president's uninterrupted rule has fed support for the Muslim Brotherhood, the conservative Sunni movement, which is feared by Copts for what it would do if it came to power in Egypt.

In an interview, the Muslim Brotherhood's spokesman, Mohamed Habib, insisted the party saw no differences between Muslim and Christian Egyptians.

"We do not discriminate against them, they are part of who we are," Habib said. "However, we blame them for not having any real political role. Politics is an open arena and they can take part of it whenever they want."

Some Egyptian officials took issue with Obama's speech for mentioning the Copts and religious tolerance. Nabil Fahmy, former Egyptian Ambassador to the U.S., said that foreign pressure isn't the answer.

"It's a problem that we have to deal with in our own society," he said. "I accept that there's a concern the Copts have in Egypt and I'm ready to discuss that here."

Home to outspoken television broadcaster al-Jazeera and the BBC co-produced Doha Debates, officials in Qatar said they have been flexible in discussing concerns about religious freedoms, and point to their allowances to Christians in their country.

In 2003, Qatari Emir Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa al-Thani allotted the land outside the capital to build churches for 28 different denominations, including Makarios's Greek Orthodox church.

It isn't prime real estate. Depending on the day and where the hot wind blows, parishioners can smell an overwhelmingly putrid stench. There is a goat farm not far away.

Still, they come. Outside its guarded and unmarked walls, cars line the road on Fridays, since they are not given a holiday to worship on Sunday. Five other churches are under construction.

Makarios said at first, many of his members were afraid to come and worship. But he expects his flock will grow soon enough. "They had had bad experiences in the past," he said. "But, step by step, they started to come."

Christopher Rosacker graduated from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln in August. He has worked for the Daily Nebraskan and held an internship at the Bismarck Tribune, in North Dakota.