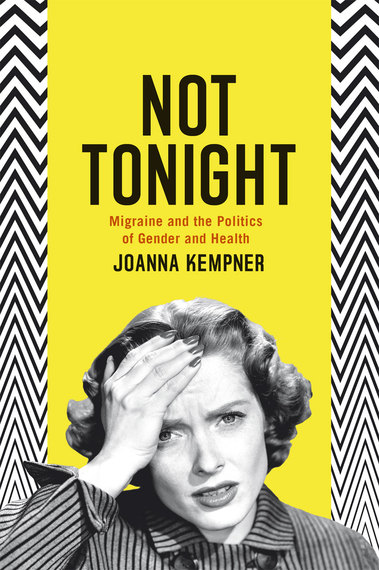

Sociologist Joanna Kempner has produced a fascinating book about migraine, women, health care, and bias. Kempner -- professor and affiliate of the Institute for Health, Health Care Policy, and Aging Research at Rutgers University -- has personal experience with migraine attacks, which started for her at 5 years old.

Since I was diagnosed last year with migraine and Meniere's disease, I've been working on a migraine-friendly diet plan and book. I was fascinated to find Kempner's book, which asks the pointed question: Does migraine treatment and research get slighted because it's primarily women who suffer?

More than 75 percent of migraine sufferers are female, and Kempner's premise is that this gender inequity makes an enormous difference in how migraine is studied and treated, as well as how migraine drugs are marketed. Her book traces the history of migraine, the perception of the "migraine personality" in literature, how treatment has evolved, and the attitudes expressed about patients in both the medical literature and recent best-selling books on migraine.

She tackles such meaty topics as how pharma companies play on women's guilt about failing at their family duties, how the recent shift to seeing migraine as a neurological spectrum disorder has legitimized both headache doctors and researchers, and the rise of the patient advocate.

I was challenged by the book, both to address my own biases and my personal experience as a patient, to re-think my response to migraine books and articles, and to question terminology. Kempner's book put my own experience into context.

I liked Kempner's even-handed approach, especially where she describes the positives and negatives of seeing oneself as having a "migraine brain." The recent shift from viewing migraine as a psychological problem to a neurological one has advantages, bringing legitimacy and possibly research dollars to what's now believed to a be complex neurological disorder.

Kempner outlines the down side, too. Focusing solely on neurology limits the potential for other areas of study and treatment, one of which may provide a part of the answer to this complex puzzle. The broken brain concept can develop into a personal identity for migraine sufferers. One indicator of this is the adoption of the term migraineur by the migraine community. She, as do I, questions the usefulness of this term, as it implies an identity that cannot easily be set aside.

I caught up with Kempner to ask her some questions:

How have physicians and migraine researchers responded to the book?

"I've been really pleased at how well received the book has been in medicine. Headache specialists have told me that they find my book helpful in their efforts to reduce the stigma of headache disorders. Dr. William Young, at Jefferson Headache Clinic, has been particularly supportive and we've even conducted some research on migraine and stigma together."

You made some challenging statements about pharma companies and advertising. Has there been any backlash? Have you seen any positive change?

"Most of what I said about the relationship between the pharmaceutical industry and headache medicine is well known in the field. Corporate influence is an endemic problem in medicine. The problem in headache medicine is that headache specialists have few alternatives -- there is so little non-industry funding available for headache research, they have no choice but to accept pharmaceutical funding.

So, no, I haven't had any backlash or heard any critiques. However, I have had some pharmaceutical companies ask if I could provide advice on upcoming campaigns."

Have any migraine advocates taken exception to you questioning the term migraineur?

"I think that migraine advocates have welcomed me as someone who is interested in reducing the stigma of headache disorders and I think that they have welcomed debate about appropriate language to use. I don't like the term "migraineur" because I think it conflates the person with the migraine. "Migraineur" makes it sound the person is actively migraineing. I'm taking a cue from the disability rights movement on this one. Just like "person with epilepsy" is generally preferable to "epileptic," I think "person with migraine" is preferable to "migraineur." In general, those who disagree do so for aesthetic reasons -- "migraineur" sounds more elegant, whereas "person with migraine" can sound awkward."

What is your biggest takeaway from writing the book?

"Hard question! I began my research hopeful, believing that scientific research could legitimate migraine. But I learned that neurobiology alone can't transcend centuries of sexism. We also have to do change the way that the world thinks about people in pain, more generally."

Has it changed your personal migraine experience in any way?

"Absolutely. I met so many courageous men and women who live in a tremendous amount of pain. I learned that I can and should be more open about the many ways that migraine has negatively affected my life and I learned that this is an issue worth fighting for."

If you're deeply interested in better understanding the migraine experience, this book is a fascinating, scholarly read.

Stephanie Weaver, MPH is a writer, wellness advocate, and food blogger. She's currently working on a migraine diet plan. Join her mailing list to keep abreast of her project.