The deaths of more than 800 people in the Mediterranean Sea on Sunday have led to renewed calls for international action to address the region's ongoing humanitarian crisis, in which thousands of migrants have lost their lives attempting to reach Europe by water.

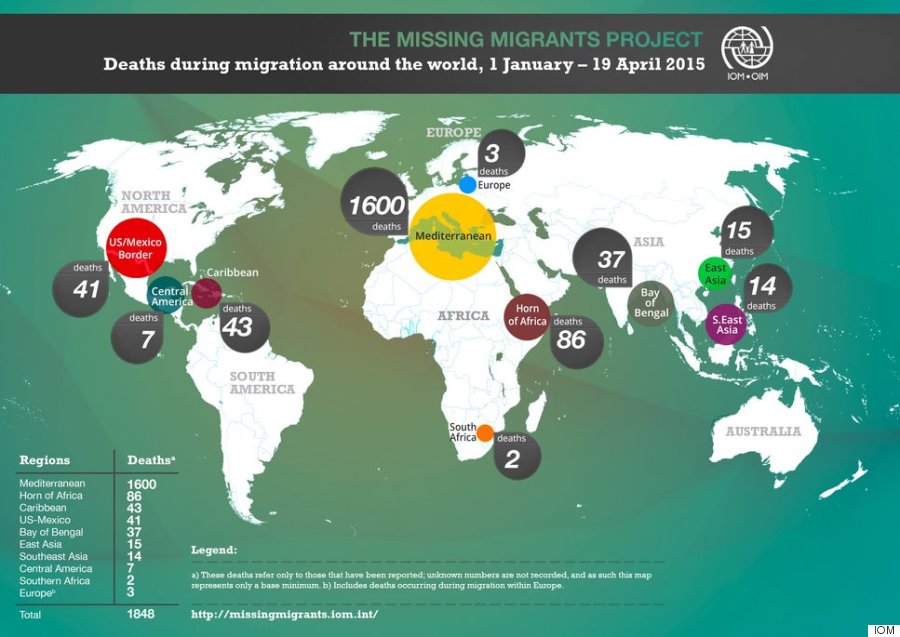

While Sunday marked the single deadliest day of the crisis thus far, it was not an isolated incident. More than 3,000 migrants drowned in the Mediterranean last year while attempting to cross from North Africa to Europe, and since the beginning of 2015, as many as 1,600 more people are believed to have lost their lives.

The high level of risk has not stopped migrants from making the journey. If anything, the volume seems to be increasing. The death toll in the first four months of 2015 was 30 times higher than what it was during the same period in 2014.

Crossing the Mediterranean is one of the most perilous ways to reach Europe. Travelers face numerous dangers, from choppy and unpredictable waters to the poor seaworthiness of smuggler's boats. Many migrants can't swim, and if their vessels are wrecked or capsized, they often drown. Those who do make it to European shores can face complicated asylum processes and even deportation. Many wind up homeless or in poverty.

Survivors of the smuggler's boat that overturned off the coasts of Libya lie on the deck of the Italian Coast Guard ship Bruno Gregoretti, in Valletta's Grand Harbour, Monday, April 20, 2015. (AP Photo/Lino Azzopardi)

Survivors of the smuggler's boat that overturned off the coasts of Libya lie on the deck of the Italian Coast Guard ship Bruno Gregoretti, in Valletta's Grand Harbour, Monday, April 20, 2015. (AP Photo/Lino Azzopardi)

After the deaths of 360 migrants off the Italian island of Lampedusa in 2013, the Italian Coast Guard launched a mission known as Mare Nostrum, or “Our Sea.” As part of the operation, five warships were put in constant patrol in the Mediterranean, aided by air support and drone surveillance. Over the course of a little more than a year, Mare Nostrum was credited with saving more than 100,000 migrants in the Mediterranean.

The cost of the mission was estimated at around 9 million euros a month, a heavy burden for Italy to bear. After repeated calls by the Italians for European Union assistance, Mare Nostrum came to an end, and the responsibility to address the migrant crisis was charged to a joint European mission called Operation Triton, overseen by the European border control agency Frontex.

Triton launched on Nov. 1, 2014, and many found the results underwhelming. “Europe's Operation Triton is a woefully inadequate replacement for Italy's Mare Nostrum," said António Guterres, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, less than four months later.

Migrants on a Coast Guard dinghy arrive at the Sicilian Porto Empedocle harbor, Italy, Monday, April 13, 2015. (AP Photo/Calogero Montanalampo)

Migrants on a Coast Guard dinghy arrive at the Sicilian Porto Empedocle harbor, Italy, Monday, April 13, 2015. (AP Photo/Calogero Montanalampo)

Frontex was conceived over a decade ago to coordinate migration issues across Europe. But analysts and activists say its missions are often underfunded and ill-equipped -- and those limitations put lives at risk.

Unlike Mare Nostrum, Operation Triton is not a search and rescue operation. Instead, its main focus is border control. Its budget is a third of Mare Nostrum's, at just 2.9 million euros per month, and it has less than 10 percent of Mare Nostrum's manpower. Frontex also has no vessels of its own, relying on member states to contribute boats and planes to its missions.

There are some smaller national and private efforts in addition to Operation Triton, such as the Greek team that rescued passengers from a recent wreck. Frontex also runs Operation Poseidon Sea, an undertaking based in Greece whose budget for 2014 was less than 1 million Euros a month.

“What we've ended up with is a much less robust program that's more focused on security than it is on humanitarian activities, so that right there is helping to put more people in danger," Daryl Grisgraber, a senior advocate with the humanitarian group Refugees International, told The WorldPost.

Frontex argues that while the agency does all it can to save lives, its main priority is border control. Search and rescue, the group says, was not part of the mandate given to it by European Union member states.

"We do not have any mandate in search and rescue," Ewa Moncure, a spokeswoman for Frontex, told The WorldPost. "Of course, when there is a boat in distress and a call comes in, we suspend all our activities and participate in the search and rescue.”

Moncure disputed a widely reported claim that Operation Triton only patrols 30 nautical miles off the Italian coast. “Our operational area is bigger than the territorial waters," she said. "In practice, the great majority of these incidents are taking place some 40 nautical miles off the Libyan coast.”

In this Wednesday, March 4, 2015, file photo, rescued migrants wait to disembark from an Italian Coast Guard vessel in Porto Empedocle, Sicily, southern Italy. (AP Photo/Francesco Malavolta, File)

In this Wednesday, March 4, 2015, file photo, rescued migrants wait to disembark from an Italian Coast Guard vessel in Porto Empedocle, Sicily, southern Italy. (AP Photo/Francesco Malavolta, File)

The Mediterranean migrant crisis comes at a moment when there are more displaced people worldwide than at any other time since World War II. People fleeing conflict, repression or starvation in countries like Eritrea and Syria report that under current conditions, they have little choice but to leave their homes in search of asylum.

Countries in the Middle East and North Africa have absorbed much of this migration -- nearly 25 percent of the people now living in Lebanon are Syrian refugees -- but many migrants are seeking to enter Europe as well.

In the coming summer months, as the seas calm and the weather heats up, the Mediterranean migrations will likely increase, if past years' patterns are any indication. That seasonal uptick could be further exacerbated by the lack of border control in conflict-torn Libya, a place that Moncure called "a paradise" for human traffickers.

Another major reason for the scaling-down of Mediterranean operations -- besides budgetary issues -- has been the concern that continued search and rescue would create an incentive for more migrants to attempt the crossing. The United Kingdom, for its part, has refused to support any such operations, citing what Joyce Anelay, the British Foreign Office minister, called "an unintended 'pull factor'" for migrants that would cause more deaths. Cecilia Malmstrom, home affairs commissioner for the EU, has also said the Italian rescue effort had the effect of intensifying human trafficking.

Critics have also charged that the EU's increase in funding to restrict migration over land and fortify land borders has contributed to the increase in migrants seeking dangerous alternative passages, and has also led to a heightened reliance on human traffickers.

Rights groups have repeatedly disputed the "pull factor" theory. Benjamin Ward at Human Rights Watch has written that the argument is "specious," and says that "even if rescue were shown to be a measurable pull, it is surely a moral failure unworthy of Europe to let some migrants drown in order to deter others."

"It's a bit of a bizarre analysis, because the fact is that migrants are going to keep migrating no matter how dangerous and difficult it is," Grisgraber told The WorldPost.

Grisgraber said she saw this firsthand while working with Syrian refugees who had tried migrating from the north coast of Egypt.

"There were people in the water watching their tiny children drown. There were people who lost entire families," Grisgraber said. "These people said nonetheless they were going to try again, because they didn't see a future for themselves in Egypt."

A migrant is helped to disembark in the Sicilian harbor of Pozzallo, Italy, early Monday, April 20, 2015. (AP Photo/Alessandra Tarantino)

A migrant is helped to disembark in the Sicilian harbor of Pozzallo, Italy, early Monday, April 20, 2015. (AP Photo/Alessandra Tarantino)

On Monday, European foreign and interior ministers unveiled a 10-point plan to increase funding for Operation Triton and expand the intervention zone, though the details remain vague. They are scheduled to meet on Thursday to flesh out the plan.

Yet already there are concerns that the proposals will fall short of what's needed.

“It took the deaths of 1,000 people in the space of a week to see EU leaders focusing on this, but it’s just not going to be enough,” Judith Sunderland of Human Rights Watch told The Wall Street Journal this week.

Critics have pointed out that even doubling the current rescue efforts -- a step that has reportedly been proposed -- would still leave Triton with less capacity than the Mare Nostrum mission, which itself could not accomplish all it set out to do.

In this file photo taken on Thursday, Dec. 4, 2014, provided by the Italian Navy, rescue crews approach migrants on a rubber boat some 40 miles from the Libyan capital, Tripoli. (AP Photo/Italian Navy, file)

In this file photo taken on Thursday, Dec. 4, 2014, provided by the Italian Navy, rescue crews approach migrants on a rubber boat some 40 miles from the Libyan capital, Tripoli. (AP Photo/Italian Navy, file)

There is also the issue that even with an effective search and rescue operation in place, the flow of migrants is unlikely to stop while push factors such as conflict and economic hardship are still going on in their countries of origin.

Migrants are seen on the shore in the eastern Aegean island of Rhodes, Greece, on Monday, April 20, 2015. (AP Photo/Nikolas Nanev)

Migrants are seen on the shore in the eastern Aegean island of Rhodes, Greece, on Monday, April 20, 2015. (AP Photo/Nikolas Nanev)

And Grisgraber told The WorldPost that sweeping changes will also need to be made to European immigration policies in order to stop migrant deaths.

"Migration into Europe from these less-developed countries needs to be regularized. There need to be safe and legal ways for people to get to Europe if that's what they want to do," Grisgraber said. "People who are fleeing persecution need to be allowed in as asylum seekers and have their claims adjudicated."

"Basically, to make it illegal to show up at a border and try to seek either protection or a better life is clearly backfiring," says Grisgraber, "and that's why we're having people die at sea."

But relaxation of immigration policy is politically difficult, especially with a number of anti-immigrant parties gaining ground in Europe and vocally opposing such measures.

Nevertheless, Grisgraber argued that the immediacy and scope of the tragedy make it imperative for the EU to change existing policies.

"People in charge are going to have to start thinking twice [about] how to deal with this," she said. "You can't have hundreds, close to a thousand people, periodically showing up at the sea border dead."