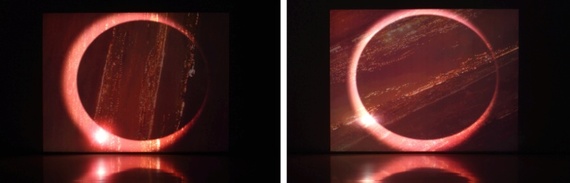

Few works of art embody the spirit of contemporary nomadism more than the projected Orbit Rosse videoscapes of Grazia Toderi (2009-2013), composed from nocturnal aerial views of glittering cities around the world. Toderi's 2013 showing at New York's Sonnabend Gallery is one of ten exhibitions shown in New York surveyed at the end of this post for embodying the nomadic view of art as a natural conduit for the vital crossculturation of our globally integrating world.

In every urban metropolis of the world, cultural nomadism is overlapping, if not yet supplanting, indigenous culture. In a typical 24-hour cycle in New York or Paris or London or Tokyo or Berlin or Sydney or Shanghai or Delhi, we typical cosmopolitans-on-the-go venture to the cinema to catch the latest film by Michael Haneke or Deepa Mehta or Laurent Cantet or Abbas Kiarostami or Shohei Imamura or Steven Soderbergh or Zhang Yimou or Alfonso Cuarón, after consuming a palatably-spiced meal at our favorite Thai or Vietnamese or Mexican or Moroccan or Ethiopian or Greek or Armenian restaurant with our newest Chinese or Nigerian or Pakistani or Bolivian or Austrian or Japanese or Iranian or Greek friend. Upon stopping off for a nightcap at a neighborhood haunt, we down our favorite mix of vodka or scotch or sake or burgundy or tequila or rum or millet beer, whereupon we say our mildly drunken and all-too-effusive goodbyes to head home to catch the latest news from Darfur or Kabul or Guatemala City or Jakarta or Caracas or Amman or Belfast, before closing our eyes for the night.

Hours later, as we unconsciously deaden ours alarms while allowing our still dream-glazed eyes to drink in the morning light cascading across our rooms, we focus our gaze upon our favorite Cote'd'Ivoire mask or Samurai sword or Tibetan Tankha or beveled Venetian mirror or French baroque gothic polychrome saint or Chinese ginger jar or Korean brass-and-lacquered chest or framed comic superhero poster, recharging our senses as motivation for another day. Then, as we struggle against inertia and gravity, we find comfort in our silk print kimono or embroidered kaftan or brightly checkered sarong or waffle weave bathrobe or loose falling kurta or open-necked galabeya or wrap-around sari or throw-over sarape, with its sensuality readying us for a bath endowed with essence of coriander from India or mango from West Indies or aloe from Madagascar or coconut from the Philippines or eucalyptus from Tasmania or clove from Indonesia, as we listen to mesmerizing techno or melodic raga or rousing marrabenta or wailing maqam or rhythmic samba or monophonic plainchant or bass-driven ska or evocative klezmer.

On the train to work we read passages from the newest novel by Orhan Pamuk or Elfriede Jelinek or V. S. Naipaul or Gao Xingjian or José Saramago or Kenzaburo Oe or Toni Morrison or Gabriel Garcia Marquez, about the conversions of, and conflicts encountered by, characters grappling with tradition and authority and prejudice to assert their individual identity. At work, we steal a break to make an e-trade of stock from the market in Tokyo or Shenzhen or Karachi or Frankfurt or London or Budapest or Istanbul or Bogota, while checking the dollar against the euro or ruble or yen or dinar or florin or peso or kwanza, as we plan our bi-annual trip abroad to Santorini or Macchu Picchu or Angkor Wat or Luxor or the Yucatan or Prague. On our lunch break, we find time to catch a museum show featuring Australian Aboriginal ground paintings or Navajo pueblo pottery or Papua New Guinea slit drums or Zapotec ceramic deity figures or Senegalese double-sided glass paintings or the new Chinese neoconceptualists. By late afternoon we're eager to finish work because we have tickets for the Russian Ballet or Afghan ustads or Kurdish minstrals or Scotish bagpipes or Turkish dervishes or Ghanaian drummers or Balinese gamelan, burning a hole in our pocket, and to which we'll drive our date in our sporty Maserati or BMW or Toyota or Chery or Citroën or Paykan or Mahindra.

Regardless in which world metropolis we reside, a single 24-hour cycle affords a sizable cross-representation of the world's cultural and industrial production. The scenario seems entirely unremarkable to the younger among us, born into the world centers of globalism. The diversity seems great to us only when analyzed in historical perspective, not when living it in the quixotic world of today's commerce and art. Privileged to international trade and travel, our ideology and practice have become the most capaciously consumptive in history. And the effect of it all, the world view that we carry around with us and espouse with great authority when among friends, may well be as capacious, if not more, as any world traveller's in centuries past.

Archeology tells us that the art world we know today has been 30,000 years in the making. Yet despite its great age, the art world has only begun to resemble the real world in its geopolitical representation. I don't mean the artworld of museums--our stalwart compendiums of encyclopedic culture born in the age of colonialist pillaging. I mean the artworld that once prided itself on leading the avant-garde charge. And yet it's this very artworld that was seriously derriere garde to the multinational corporations and statecraft that opened the world up through buisiness and finance. Even in 2013, it lags behind the global markets despite the significant number of nations coming to play a significant role in the international market for contemporary and traditional art. Only in the last decade have the former centers of civilization come to realize that as we slept in the insulation of our dominance, the notion that art knows no borders--once little more than a hot house hybrid of idyllic theory divorced from real politics--and one conveniently forgetting the long history of autocrats and states issuing artistic agendas--had been discreetly sending out roots to private collectors and institutions far outside the West. What with the vital and "new" international art markets emerging from Deli, Beijing, Tehran, and Dubai joining with markets not all that old in Moscow, Hong Kong, Taipei, Istanbul, Mexico City, and Tel Aviv, worldwide sales of art are rallying record highs. Although the stability of these markets has yet to be established, when seen against the backdrop of the greater international market, the art world offers more than record gains on investment--deep-rooted proof that the postcolonial rankings of "First," "Second," and "Third" Worlds are being vigorously challenged and discarded.

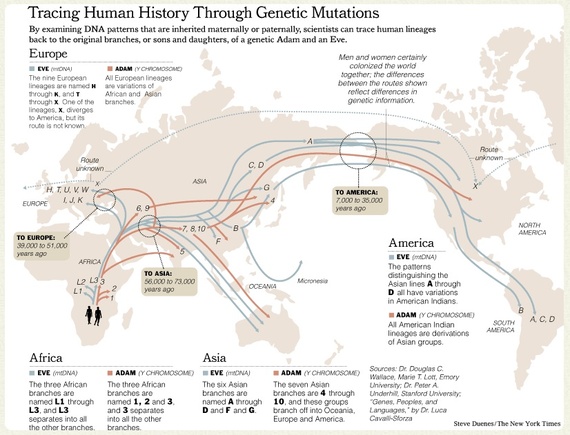

Why Nomadism? A genetic reminder that we are all the descendants of African nomads. Our aptitude for diversity is in our DNA. See the map and article.

Overtaking the new global art agora is idealism's real market progeny: a new breed of art collector and art institution ideologically nourished by decades of cultural cross-fertilization. Counted alongside collectors and institutions who favor traditional or national artists, buyers hungry for global representations of art have become so numerous and so voracious they are generating an economic windfall that showed resistance even to the recent economic recession. The steady incline in value and appeal of world art as the new "gold standard" proves idealism can and will fuel markets, especially when inflating the value of art and entertainment.

A nomadic account of trans-cosmopolitan culture such as this was untenable even ten years ago, circumvented as much from the ethnocentrism that clouded international art markets as from the monopoly on world capital retained by the West. Plentiful were the idealistic imaginings entertained by cultural theorists of what a culturally nomadic world would look like, accompanied as they were by a surge of curatorial surveys of world art in the capitals of what we could still call the Second and Third worlds. Crossculturalism may be as ancient as the trade routes, but the reflexive discourse on crosscultural exchange and assimilation is but a few decades old, and this despite that the art-without-boundaries myth has a cherished place in the narrative of Western modernism. Who can forget the charming accounts of small coteries of European avant-garde artists who in the late-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries appropriated formal elements of Japanese ukiyo-e prints and African masks in their painting and sculpture. Yet our task demands that we travel further back in time--much further--lest we end with a myopic and self-congratulatory genealogy of trade as quaint as the modernist's "discovery" (read: re-utilization) of "oriental" or "sub-Saharan" "exotica".

The greater narrative or cultural cross-fertilization is far more than some eclectic dilettantism. It follows the course of empire building and genocide. Think of Islam's Medieval warriors, sprawling from the Indian to the Atlantic Oceans, depositing their painted miniatures and geometrically interlaced ornament in the path blazed by blood dripping swords. Consider the conquistadors of Christian Spain erecting polychrome crucifixes and santos over the ruins of Teotihuacan and Cuzcuo, while holding ornamented monstrances of pristine silverwork over the corpses and chained bodies of indigenous Americans. Think also of the scourge of Mongol hordes impacting upon Chinese scroll painting and cloisonné, Persian minatures, Indian architecture, and Tibetan Thanka design, even as they both arrested and prolonged (depending on their locale) development of Byzantine painting for centuries. More recent occupations--the British in India, the Americans in Japan and Korea, the Soviets in Eastern Europe, the Europeans in Africa, the Israelis in Palestine--have generated their own cultural crosscurrents, some yet to peak. Oh, and yes, those African masks that Picasso so loved came by route of the slave trade, many with their histories of female genital mutilation euphemistically parlayed by ethnologists and anthropologists as "coming of age" rituals. And those figurative ukiyo-e prints (literally "of the floating world" of courtesans and prostitutes) beloved by the impressionists and their ilk as often as not chronicled the last gasp of indigenous pan-sexuality of which "moralistic" Western nations demanded the Japanese purge themselves if they wished to benefit from much-needed Western trade.

In short, the powerful currents of crossculturalism we witness in today's global art markets is an intricately variegated offering with a long and winding lineage. Today's global agora, at least in terms of contemporary art, is more a mongrel affair than a thoroughbred race, a mix of breeds that becomes all the more impressive when the newest players are remembered as the nations once occupied by European powers who, after decades of anti-Western posturing, today rejoin their former colonizers--this time transacting, if not soon to be dictating. the terms of cultural trade. While nationalist and ideological agendas still resonate in art markets around the world, the greater proliferation of world trade benefits the diversity of cultures. And yet the domination of the auction market by collectors of Western historical and contemporary art masters, most of which are men, is out of sync with the cultural diversity, increasing gender parity and ideological pluralism of the art and artists working and exhibiting--and most importantly, revitalizing the avant-garde--at the lower stratas of the globalized art trade.

Were it profit alone that explained this irony, we would surely find little resistance to the assumptionsed of a nomadic criteria by art critics and curators. It is too easy to attribute the new spirit of global nomadism in the art markets to the spread of capitalism and democracy throughout the old "Second" and "Third" Worlds, when the mediation is an amalgam of capital, commodity supply and demand that such ideologically regulated markets as China, India, and the United Arab Emirates also exhibit. The fact that sales of both traditional and avant-garde art, indigenous and globally modern art, is as much on the rise in these new markets resistant to democratic capitalism, indicates that the spread of nomadic diversity is ever more complex. A central ideology derived from the colonialisms of old has been virtually shredded for the secular populations of the world, and with capital redistributing itself in the former colonies of both democratic and authoritarian societies alike, the art and artists of the world's disparate cultures are being enthusiastically received by affluent and schooled audiences for both traditional and experimental production.

The disjunction between the diversity coursing through the new global art markets and the narrow, traditional intransigence of nationalist and ethnocentric criteria held by many critics and academics is made clear when we acknowledge the artworld's assimilation of an unprecedented number of artists from myriad cultures are commented on with a criteria unconsciously premised on an antiquidated, overarching order of authority and privilege--that is, the authority of the critic and curator; the privilege of the collector and museum. This criteria derives directly from the eighteenth-century European tradition of noblesse oblige, the system of privileged patronage that by the mid-nineteenth century was transferred through revolution and reform from the aristocracy to the bourgeoning class of conspicuous consumers that defined the upper middle classes. Yet, instead of revitalizing the language of criticism to mirror the new international order of valuation and exchange, many within the new class of art patrons, critics, and collectors of the Western markets retain the language and fixed values of colonialist authority. This much was evidenced in the winter and spring of 2013 with the blatant display of cultural chauvinism by the curators of MoMA's Inventing Abstraction show that perpetuates the myth that abstraction was European, while in defiance of 40,000 years of evidence clearly displaying abstraction to be globally ubiquitous.

So long as this fixed cultural ideology qualifying what art should be was confined to appraisals of Western art, the authority remained largely unchallenged. Its failure, however, is ensured when the Western ideology of art is confronted by the arts, aesthetics and culture of non-Western societies. Amid the lacuna of global aesthetics, a new and growing demand for art made both indigenously to nations and those made around the world has driven the most progressive curators and critics to adopt a shifting nomadic criteria capacious enough to adapt to the diversity of the new international markets without the impediment of overtly ethnocentric values. And yet, the nomadic enculturation to which I refer is posed not as a corrective of the art it discusses, nor is it prescriptive of a better method or model. Rather, it is posed as a counterpoint to art and artists; an alternative to the point of view presented by the artist. The nomadic shift in view underpins a reflexive criticism that is intended to prevent the discourse of art from dissolving into a narcissistic exercise of authoritarian paternity and myopic discipleship. The myopia of a criticism to which I refer fails to acknowledge what Paul de Man had in mind when he admitted that the critic's insight is identical with his blind spot, that it is exactly what she sees that prevents her from seeing beyond it.

If we learn that our propositions and our passions are also our limitations, we can realize the widest possible choice of interpretations afforded us, rather than merely ponder a narrow dialectic between the artist and critic. Perhaps that is what is occuring as the call for a criticism encouraging us to enter into the cultural terrain indigenous to its makers is growing louder. With so much new art currently emerging from vital markets around the world, much of it referring back to "premodern" ideas, traditions, rituals, and art, today's new art is best understood not as some bounded and supplanting epoch or movement, but in relation to a thriving past being revised and remodeled in new contexts today. Although artistic representations of past, present, and future show no sign of deliquescing into seamless world culture, they are overlapping, simultaneous, and syncretistic paradigms which roughly correspond to a concurrence of global civilization's preindustrial, industrial, and postindustrial societies, economies, and labor. Which is why we are being challenged more often and more diversely to look beyond categories of "premodern," "modern," "postmodern," "Western," "Eastern" art movements to consider the implications of a single world manifold swept by the crosswinds of global diversity and renewed respect for indigenous cultures. The world panorama is a perspective over-brimming with rich comparisons and contrasts that better enable us to identify and distinguish between open and emancipating models and indoctrinating rhetoric that stifles the free exchange of ideas. Exposure to this vast array of dialogue and debate better enables us to cut across the lines of identity and ideology informing theory and art. It also keeps us from being seduced into settling with, and becoming unknowingly conditioned by any one system or authority before we've had the opportunity to peruse and experience the myriad models available in a relativistic world.

Migrations Real and Ideal: The Exhibitions of 2013 (Or All the Way to Heaven Is Heaven)

Grazia Toderi, Sonnabend Gallery, September 14 - November 2, 2013:

Seen as if from a plane suspended in flight, the projected Orbit Rosse videoscapes of Grazia Toderi, 2009-2013, with their visions of nocturnal aerial views of glittering cities around the world. are in fact kaleidoscopic mirages composed from superimposed views of cities morphing continuously one into the other as they evoke the stars from which all things come. New Yorkers were introduced to Toderi's newest rotating horizons encircled by cornas of spectacular luminescence. The Sonnabend press release is one of the few in recent memory to liken a contemporary art work to Saint Augustine's "formless matter, halfway between being and nothingness," an expression of the simultaneous desire for, yet deferral of, arrival at a destination that marks all nomadism. Toderi's sustained hovering also reminds us that a permanently deferred arrival is the virtual equivalent as much of the poetic omnipresence of Catherine of Sienna's journey to heaven, as it is to Einstein's calculation that all time, past, present and future, is simultaneous and infinite at the speed of light.

Fake: Idyllic Life by Shoja Azari at the Leila Heller Gallery, November 14 - December 14, 2013.

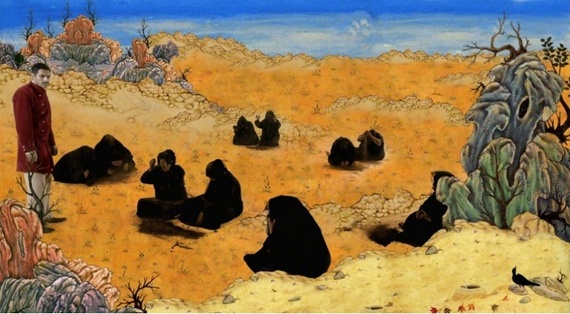

The Mourners (The King of Black), photograph and frame from the video narrative, The King of Black, a retelling of Nizami Ganjavi's epic poem, Haft Pyykar (Seven Beauties).

A finer exhibition by an artist who vacillates between admiration for, and loathing of, Western Orientalism in art can't be recalled. Despite his overt critical posturing in relationship to the cultural chauvinism of the West, Shoja Azari reaffirms the artistry, however much he mocks the colonialist stereotyping, of European Orientalist painters such as Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863), Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904), Théodore Chassériau (1819-1856), Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps (1803-1860), and William Holman Hunt (1827-1910). It's a predicament that every admirer of both Orientalist painting and true Middle Eastern culture, art, architecture, and of course the people of the region, must weigh out the balance for in a critical nomadism.

Refreshingly, Azari shows us it is possible to admire both critic Edward Said and painter Jean-Léon Gérôme for the contingent, if shifting, realities that each brought to the table of crossculturalism. Of course Azari has the moral highground beneath his feet, as well as counting among the millions of Iranian-descent who share in the indignity of being identifed with stereotyped Orientalist subjects. He also has been encultured by the great schools of Persian, Mongol and Safavid miniature painting and epic poetry that has saturated his vision and narrative lyricism as a filmmaker and artist. But whether or not he admits it, the art of Islam and other Middle Eastern institutions also have a colonialist history and cultural chauvinism attached to them. The good news is that nomadism liberates us from the prohibitions and closures of non-relativistic ideologies that create opposition to one or the other culture. It is this nomadic attitude Azari appears to adopt when he shows off how richly informed he has been by both the extravagant pictorial innovations of Orientalist painting and the Islamic arts of which most Westerners, by contrast, have been sadly bereft.

Bidoun Magazine's Senior Editor, Negar Azimi, put it best when he wrote, "Fake: Idyllic Life creates a space in which radically different histories rub up against one another; the 5th century intermingles with the 12th, the 21st, and the 18th. ...This is a story about the endurance of caricatures and the porousness of histories. This is a story about how we, as humans, project our desires. This is a story about how we tell stories."

Banquette of Houries (The King of Black), frame from the video narrative, The King of Black, a retelling of Nizami Ganjavi's epic poem, Haft Pyykar (Seven Beauties).

Isaac Julien, Playtime, at Metro Pictures, November 7-December 18, 2013

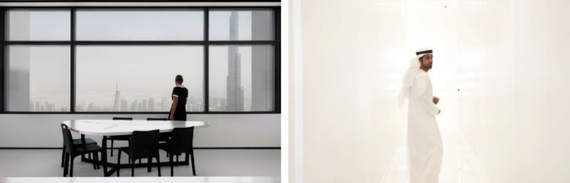

Left: Horizon/Elsewhere, 2013. Right, Mirage, 2013. Two frames from the projected video, Playtime, 2013. The view of the world's tallest building, the Burj Khalifa, tells us we are looking out from the Dubai home of an exceedingy high-net worth tenant, perhaps an oil-rich sheikh, such as the gentleman turning to look back at us.

Left: Horizon/Elsewhere, 2013. Right, Mirage, 2013. Two frames from the projected video, Playtime, 2013. The view of the world's tallest building, the Burj Khalifa, tells us we are looking out from the Dubai home of an exceedingy high-net worth tenant, perhaps an oil-rich sheikh, such as the gentleman turning to look back at us.

Isaac Julien's video fusions of narrative and documentary genres give wide berth to the interplay between speculation and evidence, myth and verification, and to such a high degree that we can't walk away from a work such as Playtime with any real sense of how much his stories are scripted or factual. What makes Julien stand out as one of the more ambitiously nomadic artist-commentators in recent years is the global reach of his productions, the extensive travel required in the search for case studies, and the counterpointing of such cultural divisions as class, race, creed and gender in the search for true democracy. At the same time, Julien frustrates the viewing public that hopes for some climactic resolution--or any kind of closure to the story. But given the artist's Brechtian inclination for employing distancing effects that keep audiences from falling prey to the numbing formulas of entertainment, Julien curtails his content to the political and economic structures underpinning his subject's conditioning. He also values sustaining the social tensions within his stories, rather than imagine fictional reconciliations, as well as ignoring conventional narrative structures that prescribe a beginning, middle and end to a story. In short, the narrative resolution we may expect or hope for will likely not be forthcoming.

There is also Julien's keenness for examining the many facets of opposing and competing interests manifest in a given economically-defined social relationship that implies, if not exposes, the ideological and economic forces invisibly at work in keeping people apart. Julien's favorite force is, not surprisingly, the dreaded opiate of capital. To this end, while the three stories within Playtime resemble modern adaptations of episodes in Chaucer or Dickens, Julien announces they are all about the indictment of capital as a disruptive force. We see this in how the video navigates among three cities that are, in Julien's words, "defined by their relationship to capital: London, a city transformed by the deregulation of banks; Reykjavik, where the 2008 crisis began; and Dubai, one of the Middle East's burgeoning financial markets." If this sounds like a Marxist cliche in the most common sense, it is because capital is universally real. Still, the cliche reduces the London narrative (with James Franco) to parody and the Reykjavik story to bland, overly formalist ennui and predictability.

The most compelling of the three stories composing Playtime is that of a migrant woman who discovers her overwhelming alienation has less to do with being a foreigner in Dubai, than does the oligarchical imperative to make Dubai a city that disallows assimilation of the classes. Julien tells us that Dubai has been designed and engineered to be exclusively the playground of the highest net-worth class in the world. Even the Marxist cliches--which would sink a mainstream story of this ilk--are in this story riveting for enhancing a simple anecdotal account of a woman who has left her children in the Philippines to take on a job as a domestic in Dubai to support them. It's the detail and emotion Julien allows into this sketch of a life that makes it transcend the parody and formalism rendered in the other two stories sharing the Playtime title less successfully. But Julien's reliance on the old Brechtian distancing effect provides the restraint required to keep the cliches of the maid's tale from erupting into melodrama. Of course, any Brechtian storyteller knows that melodrama is defined chiefly by the classes having the luxury to overreact with dramatic license. But we might argue that there is no cliche or melodrama relevant to the working poor when the working poor have so little time or energy to consider the aesthetic merits of the effects of their own poverty and dependence on a hierarchy of employers and institutions conveyed through trendy art.

Julien's resolve to film only the maid's account for her employers's alienating behavior opens him to the charge of providing one-sided views. We never witness the maid in the presence of her employers. We're only served the briefest glimpses of the class for which Dubai was built. That and glimpses of the Dubai towers that are coming to represent the self-imposed isolation of the austentatiously rich, whose only apparent interest is to protect themselves from the hordes of have-nots. To this effect, the views of skyscrapers seen from condo windows high above the ground reinforce the impression that the transglobal oligarchy is set on segregating their luxurious existence from the social elements who would overrun their playground given the chance. At least that is the fearful rationalization that Julien imagines the rich tell themselves to cover their loathing and indifference.

Playtime, installed at Metro Pictures. A maid's walk through the desert to work conveys the secret of Dubai: that it was built to be a citadel of the rich far removed from the environs of the the populace of low-net worth. The Dubai episode of Isaac Julien's Playtime is nothing if not a tale of two classes.

Playtime, installed at Metro Pictures. A maid's walk through the desert to work conveys the secret of Dubai: that it was built to be a citadel of the rich far removed from the environs of the the populace of low-net worth. The Dubai episode of Isaac Julien's Playtime is nothing if not a tale of two classes.

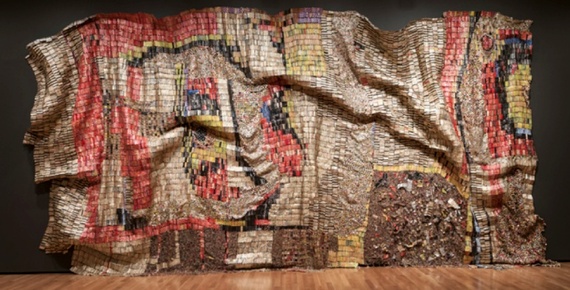

The Sculpture of El Anatsui at the Brooklyn Museum, February 8-August 18, 2013

What began as a melding of cliches--an artist from the continent most associated in the popular imagination with nomadic wanderers; the production of African cultural monuments from recycled refuse dumped on the continent by the industrialized powers--ends in an alchemy that has made the Ghanaian-Nigerian artist, El Anatsui, Africa's most renown representative of the nomadic fusion of global cultures. That his materials come by way of the world's industrial discards, not to mention its labor, is an irony not lost on the global institutions that have exhibited and sold his work. That his work now commands the attention of museums in capitals the world over reflects the Africans' resolve to turn what the rich nations neglect and squander to their advantage.

We may never know, as El Anatsui himself doesn't, who it was that mined, engineered, designed, produced, transported and ultimately recycled the materials that make up the mesh, warp, weave, and reflecting metals of his assemblages. We could be staring at a construction made up of foundary metals and never realize that our grandparents or parents helped to manufacture them. The beauty of this nomadic formula is that it attunes us to the value of lost histories, unknown degrees of separation, kinships and shared DNA yet unrecognized. In this respect, the circulation of El Anatsui's art more than expands our view of art by prying our attention away from the auction houses and celebrity artists who command media coverage yet represent no more than an infintessimal fragment of the art made in the world. El Anatsui makes us keenly aware of the cycle of production that mirrors our own human demise and resurrection through the often invisible legacies we leave in all that we make.

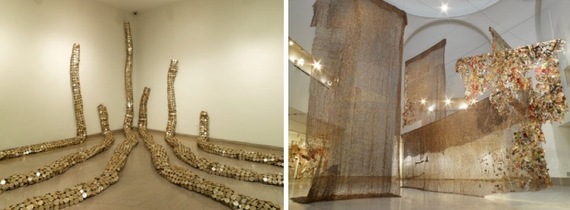

Left: Drainpipe, 2010, tin and copper wire. Right: Gli (Wall), 2010, aluminum and copper wire. Photos courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum.

Olu Oguibe and Carl E. Hazlewood: Five Myles Gallery, November 2-December 12, 2013.

Olu Oguibe. Left: Sarcophagus of a Boy With a Gunshot Wound, 2013. Right: Seed: 7,000 Rounds, 2013. Photos: Arlington Weithers.

There was a time when it was assumed that because a person hailed from a different part of the world, they must possess a different way of seeing. Today, as a result of decades of crosscultural assimilation, what I call nomadism at work, we are more aware that differences among people aren't always as pronounced as once was assumed. This is particularly true of the people who have assimilated according to their own criteria of self-assurance within the culture of their immigration as well as because we who are naturalized citizens have become better attuned by their presence to the many things that we share. And yet there are occasions upon encountering the art or writing of even the most presumedly "thoroughly assimilated" immigrant, that we have before us a work of manifest difference--an understanding--that stands out from the norm of the given, adopted culture. This seemed the case to me immediately upon acquaintance with the two-person show by Carl E. Hazlewood and Olu Oguibe at Five Myles. The difference was significant enough for me to consider if it mattered that Hazlewood hailied from Guyana, on the northeastern coast of South America, while Olu Oguibe immigrated from Nigeria, on the western coast of Africa. I continue to question whether the intricate dialogue I found in their art is unique because they intuited some remnant of a trans-oceanic dialogue that rose up to govern the relay evident between them in their exhibition, especially in its more improvisational installations.

What stood out as particularly different than most other two-person shows is the chilling effect Oguibe's work had on Hazlewood's work. In fact, Oguibe's sculptural metaphors spoke to me instantly of the history of African colonial and inter-tribal warfare. And they brought that dark context to bear on Hazlewood's otherwise elegant, yet contextually-receptive, abstractions. Was this only my projection? I think not. I'm inclined to believe that I read the signage of two minds who were somehow encultured similarly, yet differently than I--and in a most welcome and enthralling way.

Oguibe's art spoke to me of recollections of modern human savagery--an inhumanity that particularly resonated in Seed: 7,000 Rounds, with its amunition shells laid out for inspection on the same crime-scene yellow tape that coursed through Hazlewood's wall compositions; and Sarcophagus of a Boy With a Gunshot Wound, an austere yet moving tribute to Trayvon Martin. In their simplicity and elegance, Oguibe's work harmonized classically with Hazlewood's ephemeral abstractions at the same time that they compelled me to see in Hazlewood's open-winged combine, Angel of Mercy, the apparatus of bondage, torture, suffocation, flaying, and its cleanup.

Oguibe has denied intending a postcolonialist context, yet whether he was conscious of it or not, he expanded the show's nomadic indexing with what he calls the "repurposing" of tribal masks throughout the space. The mask referred to above, from the Lega society of Congo, Oguibe recounts "would have been used by a younger or lower level member of the men's society. The masks are not worn on the face, though, so, using it as a death mask is not in any way related to its original purpose or use"--hence Oguibe's choice of the term, 'repurposed'. But this mask is also the remnant, whether it is an original or a copy, of the masks made before and during the colonialist epoch. The masks thereby carry the signage of the struggle between an indigenous culture and the colonialist occupier. Showing such signage in conjunction with ammunition and the crating that it comes in cannot avoid being associated with the era of Frantz Fanon and the liberation movements of Africa and South America.

Hazlewood, meanwhile, added formal nuance to Oguibe's choices, playing modernist to Oguibe's traditionalist, then again modernist to Oguibe's postmodernist. The interplay took many turns that in relativist fashion, made the two men appear skittish about committing to any one interpretive theme or context. Then again, Oguibe's reliance on found objects reflected back at him with Hazlewood's cut-and-hung lines and contours made from string and paper, shadow and light, curving, bending and reflecting through real space. The conversation between the contemporary and the traditional, the Guyanese and the Nigerian, the American culture of their assimilations, all exposed the multi-chambered heart of nomadism to be centered on unfettered communication and honest remediation and celebration of differences.

Yael Bartana, And Europe Will Be Stunned, at the Petzel Gallery, April 4 - May 4, 2013

Scene from And Europe Will Be Stunned, by Yael Bartana, 2009.

A fictional movement demands that Jews be granted the Right of Return to Poland.

We heard much in New York about the three-part video fiction made by Israeli artist Yael Bartana under the collective title, And Europe Will Be Stunned, after they were shown in 2010 at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, and again at the Polish Pavillion in the 2011 Venice Biennale. But without seeing them, few seemed to be able to make much sense from the reports about their elaborate fictional staging of a movement of Jews demonstrating in Poland for their Right to Return to the country Jews had been expelled from in 1968. After finally viewing the films at the Petzel Gallery in New York this April, even more confusion and debate ensued among various New York art circles, as it had most everywhere the films had been shown.

Debators of the work squared off. The holocaust and subsequent expulsion of Jews still being relatively recent history, with victims still alive, compelled some of us to see Bartana's work to be a call for reparations. But by whom? And what would reparations imply to the ethnic and religious groups similarly displaced by genocides and violent occupations around the world? Certainly the antisemitism of the prewar Germans, Poles, Russians, Slavs, etc. are to be enjoined. But what are the implications to those Israelis who oppose the Palestinian Right of Return? Even we Americans have failed the Native Americans who want to return to their tribal lands, so how can we comment without hypocrisy being charged?

Bartana has stirred what may be the most complex and heated issue of the modern era, but her pious narrative struck many as manipulative--so long as it was seen as pious. Others saw her films to be no more than parody, particularly in their ironic centering around a charismatic figure (void of charisma, from where I stood). Often the simplistic platitudes fell flat, appearing naive and pointless, narcissistic, even irresponsible. If ever taken seriously by any one of the body politics invoked, the film could prove a flash fire of dissent, violence and strife.

Only the nomadic passion for freedom of migration, and the formation of global yet indigenous exchange that flourishes under a no-border policy, seem to explain Bartana's choices. All other political contingencies burden the three films to the point of becoming cross-purposive and conflictive. If indeed they are motivated by the benign nomadism they seem to depict, we may be justified in our exhilaration at the sight of artists such as Bartana making activism an art of attempting to reverse the course of political and moral history. And why not? Artists have always been at the forefront of change, whether radical or reactionary, for having the means and know how to construct the signage that alters, disseminates and perpetuates cultural codes.

Even more cross-purposive is the preference of some artists for the aesthetic conventions of irony and ambiguity while waging something that appears to be activism but which is too restrained by the irony and ambiguity to take root in the culture significantly. Very few succeed with this conflation. Bartana may be one who comes close to succeeding in that she has generated considerable discussion world wide.

Frame from Yael Bartana's And Europe Will Be Stunned, 2009, in which a fictional Jewish movement proudly shows off the racial diversity

that is to compose the new universalist-utopian face of modern Jews.

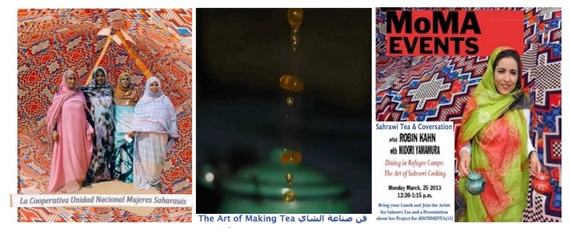

Robin Kahn with Midori Yamamura, Sahrawi Tea & Conversation, Dining in Refugee Camps, and the Art of Sahrawi Cooking, the Museum of Modern Art, March 25, 2013

There are few recurring global exhibitions of contemporary art more renown, prestigious and selective than dOCUMENTA, held every five years in Kassal Germany. Which is what makes it so very remarkable that one of the highlights of last year's dOCUMENTA 13 was the inclusion of a refugee encampment made by what are arguably among the least known people on the earth--the Sahrawi of North Africa. The inclusion of the Sahrawi women's cooking and tea arts organized by New York artist Robin Kahn at Kassal opened the door to touring opportunities, including the MoMA Events platform. As with their weeks at dOCUMENTA, the touring events include dining and tea with the women camp members of Sahrawi. But Kahn's greater motivation is to inform Western audiences, through informal conversations over Sahrawi tea and meals, of the political plight of the Sahrawi nomads of North Africa and their ongoing struggle for independence.

For Kahn, making art has come to mean talking about and sharing the culture of a country on the North African Atlantic coast that has been illegally occupied for 38 years by the kingdom of Morocco. After living in the camps for extended stays, Kahn created the book, Dining in Refugee Camps, The Art of Sahrawi Cooking in 2009 and brought it back to New York with the idea of approaching NGOs to fund its publication. When the book commanded an invitation for Kahn to organize an interactive installation for the 2012 dOCUMENTA, Kahn immediately saw the project including the Sahrawi women. It was an opportunity to inform Europeans and Americans of a side of Islam most people in the West know little of. The Sahrawi, Kahn tells us, are a matriarchal Muslim society in which "women have built the infrastructure of buildings, the education system, wrote their own democratic constitution-in-exile, all the while that they legislated women's equal rights".

The Sahrawi tea and cooking projects often include the buiding of tents (Jaima), which function as the center of family life, or in the installations for the entertainment of guests. The wearing of handmade clothes made of natural products is also shared to provide for as complete an emersion into the lifestyle of the Sahrawi men and women for as long as a festival or event might last. Most accessible to even the most reticent viewers are the meals and tea ceremonies that are open to all. "It begins with a long tea ceremony," Kahn informs, "where, in between multiple brewings, you relax, play or enjoy music. Then large plates of food arrive. As you share various inventive and delicious dishes, you start talking about who you are and they start telling you their story. In between helpings, you might break off into smaller conversations or grab a pillow and take a nap."

The Eternal Present by Park Sang-Ho, January 29 - February 2, 2013, and War is for the Living, February 12 - March 23, 2013, both at The Sylvia Wald and Po Kim Art Gallery, curated by Chuong-Dai Vo and Midori Yamamura.

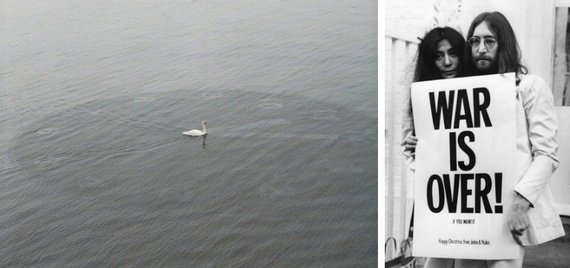

Two exhibitions: Left: Park Sang-Ho, The Eternal Present, photographs and artwork of a sublimely emphemeral and nomadic nature. Right: War is for the Living, presided over by the spirit of Yoko Ono and John Lennon, literally with this photo document of their 1969 antiwar action War is Over! If You Want It.

The necessary relationship of nomadism to war conjures predominantly images of inhabitable miseries; of passages from militarized zones; of peoples robbed of their pasts, their loved ones; of escape with one's own life and little more; and for so many not even that. Art during war ceases for those at its epicenters. The only nomadism operative are the channels of collective motions conducted in two opposite directions: the migrations of civilians out of combat zones and the forward and seemingly perpetual thrust of recruits replenishing the soldiers migrating to the charnel. The streams in both directions seem never to end, as if all is movement and little else. That is until movement is no longer possible, no longer desirable, in the desperation for rest. Then the insufferable crowding begins and the nomads officially become refugees.

A retrospective nomadism immediately after war is almost unconsciously animated, as people from all walks of life mill about, many in search of what they lost, others estimating the worth of what they're left with, the poorest searching for a place among the ruins no one else wants, the richest surveying the opportunity for further enrichment from the spoils. Always there are the returns made in reverential remembrance, some in grief, most seeking relief and consolation for agonizing recollections. And then the art making resumes, usually in commemorative waves, timed, made urgent, by the expectation of anniversaries.

It is rare that art is made to commemorate peace without reference to a specific war, but the exhibition War is for the Living did just that. Of course, the Iraq War had just ended--if that is what the pull out of American troops can be called. Afghanistan was being slowly and agonizingly phased into an occupation-by-drones and stealth fighter jets, ensuring, however unintentionally, that fewer Taliban are killed while more civilians die. Mention of 9/11 still inspires hushed reverence, but the collection of artists and their friends that gathered for the show's opening at The Sylvia Wald and Po Kim Art Gallery, barely a ten-minute walk from Ground Zero, was motivated by something else again. Something timeless and universal. The Dream of an end to all war.

The reflection on war has throughout the century-long burgeoning of the media-age grown into an impressive and irrepressible global antiwar movement. The antiwar sentiment continues to grow to the point that many governments of the world are finding themselves increasingly restrained by a majority of its middle-class citizens. Amid this democratic counterforce to hostilities, it is only natural that a conceptual nomadism--that is a romanticized desire for free passage in spite of the existential and international constraints imposing constant observation and controlled signage to temper our romance of migration, continues to flower in our cultural minds, if not in our everyday, sedentary lifestyles. And so we turn to our artists to provide an unbridled, if largely imaginary and virtual, nomadism. When true migratory nomadism is constrained by borders and legislatures, the signage of nomadism becomes the collective of differences found among humanity, the most salient being a collective of races, nationalities and faiths unified to achieve lasting peace. Yes, it remains a dream, but an exhibition dreamt it for a month no less significantly to those who saw its art.

This is why, after the subjective relationship of the artist to war, the curators Chuong-Dai Vo and Midori Yamamura, both of whom are artists, made global representation their key organizing principle for the invitation of participating artists. Here I defer to their press release and to other media sources for the artists' profiles. According to NYARTBEAT.COM, the artists include the Japanese American community activist, Tomie Arai, whose Momotoro/Peach Soy revisits the narrative of a Japanese folk tale by adjoing largely found and self-made images to re-enact the propaganda issued by the Japanese military during World War II. Kenyan-born, ethnic Indian artist Allan deSouza, participated by constructing photo-based visions of terrains suggested by daily detritus that matched his memories of the surroundings of the sectarian violence he has over the years observed.

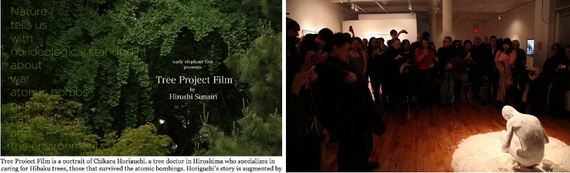

Left: Hiroshi Sunairi, Title frame from the video, The Tree Project, 2013. Right: Việt Lê performs Incredible Indelible Invisible Man at the Valentine's Day opening reception for War is for the Living.

Left: Hiroshi Sunairi, Title frame from the video, The Tree Project, 2013. Right: Việt Lê performs Incredible Indelible Invisible Man at the Valentine's Day opening reception for War is for the Living.

Japanese artist Yoshiaki Kaihatsu produced an awe-inspiring circular floor installation from the dust collected at the World Trade Center site. Brooklyn-based Hiroshl Sunairi turned to his Japanese background for inspiration when dispensing seeds from trees that survived the atomic bombing of Hiroshima to people who promised to plant them. He also screened his much-lauded 2013 video, The Tree Project, which doubles as an antiwar artwork and a portrait of Chikara Horiguchi, a tree doctor in Hiroshima who specializes in caring for Hibaku trees--the name for the trees that survived the atomic bombings. Photographer Nina Berm screened her video, Homeland, made between 2001 and 2008 to document the militarization of American life in the official effort to prevent another 9/11.

Simon Leung screened War After War, his collaborative video with Warren Niesluchowski, a former World War II refugee and Vietnam War deserter, "whose life foregrounds the ethical challenge of reciprocity and hospitality". Artists Nancy Hwang and Robin Kahn staged two performative installations showing Kahn's dOCUMENTA (13) project video about the Sahrawi women struggling for independence from Morocco and afterwards promoted activist conversations over Sahrawi tea and dining. Investigation into the "irreconcilability of war memories" among journalists and government officials motivated Baghdad-born Paul Qaysi's Misprints photo series, which he describes as "purposely-blurred images of U.S. military activity in Iraq that provoke questions about how news organizations represent war." Vietnamese transnational artist Dinh Q. Lê's photo-weavings, The Hill of Poisonous Trees , have been made as indictments of war crimes through an invocation of the ghostly countenances of people who disappeared during the Cambodian Genocide, while recalling the art of the artist's Khmer ancestors who the genocide victims have joined. In contrast to Dinh Q. Lê's mysticism and indictment, Vietnamese War survivor, An-My Lê choose to exhibit forgiveness represented by documents of the scientific, exploratory and humanitarian missions conducted by the U.S. military in Vietnam since the war's end.

Another spirit presided over the entire month-long proceeding in the image of John Lennon, who appears with Yoko Ono in the famous document of their 1969 anti-war public art work, War is Over! If You Want It, loaned to the show by Ono as testament that "ideation is a powerful tool for social change".

Park Sang-Ho, Heavenly Nomad, shown in The Eternal Present at The Sylvia Wald and Po Kim Art Gallery, January 29 - February 2, 2013.

Park Sang-Ho, Heavenly Nomad, shown in The Eternal Present at The Sylvia Wald and Po Kim Art Gallery, January 29 - February 2, 2013.

Timehri Transitions: Expanding Concepts In Guyana Art, The Wilmer Jennings Gallery at Kenkeleba House, January 27 - March 9, 2013, curated by Carl E. Hazlewood. With exhibiting artists: damali abrams, Carl Anderson, Dudley Charles, Victor Davson, Marlon Forrester, Gregory A. Henry, Siddiq Khan, Donald Locke, Andrew Lyght, Bernadette Persaud, Keisha Scarville and Arlington Weithers

Left: Marlon Forrester, Black Basketball, mixed media and paint. Center: Andrew Lyte, untitled, steel oil drum and mixed media. Right: Gregory Henry, untitled, mixed media.

Left: Marlon Forrester, Black Basketball, mixed media and paint. Center: Andrew Lyte, untitled, steel oil drum and mixed media. Right: Gregory Henry, untitled, mixed media.

Curator Carl E. Hazlewood, who hails from Guyana, assembled close to 40 works by 12 artists of Guyanese descent, many of whom can trace their ancestry further back to East Indian and African origins. The word 'Timehri' in the show's title refers to the Neolithic artists of Guyana, who some 2,000 years ago produced the petroglyphs painted onto stone at the interior of Guyana. All the artists, except the sculptors Donald Locke and Andrew Lyght, require introduction to wider audiences in New York. But that, combined with the overall quality and diversity of the work, is what made the show vital to the overall experience, especially within the context of the nomadic integration of artists from outside major power centers generating new streams of thought, energy and experience into the global art experience.

Although a good deal of the work was comprised of Guyanese- or other cultural-specific signs and objects embodying social, spiritual and natural attributes of the Guyana rain forests and the techno-commodified urban centers, there was also a fair display of work exhibiting the universal language of formal concerns conveyed abstractly by line, color, structure and process. Much of the work figuratively or metaphorically referenced popular culture, media, myths and sterotypes, and of course the "obligatory" citique of the capitalistic structure of Western culture.

Works that stood out for departing from these conventions usually projected a biting political or nostalgic subtext. In other works, even non-Guyanese viewers could easily comprehend the artists' poignant longing for some sight, sound or smell of the country of their childhood. The weightiest commentaries suggested a psychological and societal downside to migration even long after arriving in the mecca of their dreams. The most powerful work in the show conveyed some sense of the conditions of migration that prove disadvantagous for the losses accumulated with assimilation into the host culture. But some of the art concerned itself with making clear that such disappointments pale when compared to the conditions facing those who have little hope of migration. The Wounded Canvas: Lotus in Springtime, Bernadette Indira Persaud's deceptively painted diptych of a floral garden at the edge of the rainforest, betrays its idyllic beauty with a near-unnoticable bleeding bullet hole painted in the lower right corner, and next to a camouflaged, smoking assault rifle barrel shooting into the jungle. The artist's graphic commentary references the ethnic tensions between Guyana's Indo and Afro populations, which in turn informs both political allegiances and has spurred a series of high-profile murders and massacres in recent years. For those directly affected, a case can be made for assuming a lower status in a foreign place that offers safer haven, even opportunity, despite the bigotries of difference that may be endured.

Marlon Forrester is a sculptor who tackles just such a predicament in his art, using humor as a mitigating channel for the steam ventilating in the face of overwhelming racial cliches. As a black man, he is especially sensitive to the stereotypes attached to the black male body in the U.S. and the sustained ghettoization facing young African-American males in sports, however exalted and glamorous their rewards appear on the surface. In this vein of commentary, Forrester has produced a biting metaphorical icon in Black Basketbal, his sculpture comprised by a basketball painted jet black and endowed with a pair of paint-encrusted sneakers dangling from either side. So scathing is the work's satire, it's been likened by Huffington Post's Marcia Yerman to a contemporary "shackles and chain".

Keisha Scarville's Passport Series issues the most poignant note in the show, while also being among the most relevant to the concerns of nomadism in art. The sentiments arise from the work's departure from the artist's father, or more accurately from the father whose early passport photo survives his absence. Taken in conjunction with the seemingly obssessive attention paid to its mutation in the artist's hands, implies a healing process filling the void of his absence, while the photo itself provides a psychological bridge to his former presence. The series is psychologically complex, yet openly personal about the layers of transformative gestures and obfuscations that, in their fetishizing ritualization, are sought to mediate and heal the scars of the artist's personal and societal history. At the same time, the work conceals both the catalyzing and the disruptive forces swaying the impact of immigration on the immigrant--and particularly on the immigrant's child when separation results. In the absence of facts, the viewer can only summon a litany of circumstances concerning relationships impacted by migrations. Is the daughter of the immigrant faced with a broken home as a consequence of the migration? Has there been not only the loss of a father or mother, but also the loss of a vital, communal and historical legacy absent in the culture of assimilation? The work convinces compellingly that not all of the nomadic process is liberating, and the sense of loss that permeates Scarville's Passport Series speaks of the injuries that migrations inflict.

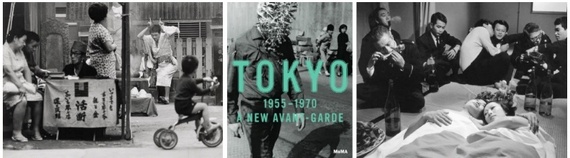

Tokyo 1955-1970: A New Avant-Garde, The Museum of Modern Art, November 18, 2012-February 25, 2013.

Left: Hoso Eiko, untitled, 1968. Center: MoMa catalogue, 2012. Right: Still from the film Koshikei (Death Hanging), directed by Nagisa Oshima, 1968.

Left: Hoso Eiko, untitled, 1968. Center: MoMa catalogue, 2012. Right: Still from the film Koshikei (Death Hanging), directed by Nagisa Oshima, 1968.

One might question whether a cultural upheaval that was forced on a people by the circumstances of nuclear annihilation and foreign occupation could count as a nomadic episode in the history of a civilization. But given that so many nomadic peoples in history trace the origins of their migrations to a national or natural paroxysm, some so distant in the past as to be beyond memory, the searching for vital cultural forms outside the national model that brought the Japanese tragedy and shame in 1945 should be regarded as no less a nomadic searching than any other national or ethnic recourse to outside stimulation in desperate times.

The certainty is that the kind of collective nomadism that the Japanese artists and their public reached for as their nation struggled to transform itself from a war-ravaged place with a living memory of horrendous war crimes committed in the name of nationalist supremacy, was the one acceptable alternative to the kind of historical amnesia that would make any and all recovered sense of esteem a lie. Looking to other nations and cultures, especially on the winning side of the war, and certainly those ravaged by the Japanese war machine, could only at the time have seemed to be the best possible path for transformation, based as it was on an honest admission of culpability in the war, combined with an assimilation of the arts and cultures of the nations the Japanese military had wronged, while purging its own culture of all remnants of the colonialist culture that had generated aggression.

In assembling Tokyo 1955-1970: A New Avant-Garde, MoMA brought together numerous iconic works from the period of Japanese reconstruction. Artists in the exhibition included collectives such as Jikken Kobo (Experimental Workshop), Hi Red Center (Takamatsu Jiro, Akasegawa Genpei, Nakanishi Natsuyuki), and Group Ongaku (Group Music); critical artistic figures such as Okamoto Taro, Nakamura Hiroshi, Ay-O, Yoko Ono, Shiomi Mieko, and Tetsumi Kudo; photographers Moriyama Daido, Hosoe Eikoh, and Tomatsu Shomei; illustrators and graphic designers Yokoo Tadanori, Sugiura Kohei, and Awazu Kiyoshi; and architects Tange Kenzo, Isozaki Arata, and Kurokawa Kisho. MoMA also assembled a 40-film retrospective that featured filmmakers Teshigahara Hiroshi, Shindo Kaneto, Imamura Shohei, Oshima Nagisa, Matsumoto Toshio, and Wakamatsu Koji.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.