When you channel surf network TV this fall, you'll catch promos for a whole host of new "must sees." There will be that sneak peek of an ABC show about the return of deceased loved ones. On CBS, you'll probably see a clip of some enigmatic new series called Beverly Hills Cop and think the title sounds awfully familiar (and that Brandon T. Jackson isn't exactly an Eddie Murphy doppelganger). Some of these series may go on to become iconic shows that shape the zeitgeist as we know it. Some will earn their creators the dubious "voice of a generation" distinction. A few might air for years and years. But most will flop.

My Generation. Do No Harm. Zero Hour. Lone Star. Utter. Ratings. Flops.

The flip from a network's heavy promotion and preemptive media buzz to the flop of dismal ratings and chirping crickets can be John Kerry or Mitt Romney-esque in dramatics. What casual viewers probably don't realize is that for every drama that makes the network's schedule -- even including the total misses like Zero Hour which was pulled after three episodes -- there are about 54 dramas deemed not good enough to even make it that far.

Each summer and early fall, network executives buy about 60 dramas and 60 comedies to develop into TV shows. Of each group of 60, about 10 will make it to pilot -- with actors, sets and budgets ranging from a couple million to almost 20 million (if dinosaurs are involved). And of these 10 pilots, only about six will ever make it to air. If a network buying a script is the equivalent of running a 10K, a series going a few seasons is an Ironman.

Network executives often use focus groups to help determine which pilots to order (can you say groupthink?). As Brian Stelter wrote in his New York Times piece, "Few TV Shows Survive A Ruthless Proving Ground", "...it is a largely unscientific process, they say, one that has far more to do with art than science. They talk in terms of 'swings,' 'home runs' and 'batting averages,' but there is no 'Moneyball' of television, yet."

But that's dumb. So I made one. I have such a system -- a number-crunching analysis that can predict the success of a TV pitch more accurately than can even the smartest, most seasoned and creative television executives. Smart -- and not-so-smart -- TV execs, after all, are influenced by a number of psychological phenomena, including:

- Mere Exposure Effect: they buy projects from a writer simply because they've worked with him or her for years. Maybe they like the way they smell. Abercrombie?

- Primacy and Recency Effects: they like the first and last pitches they hear.

- Benefit of the Dollar: a belief that the more expensive writers are the better writers.

- Preference Adjustment: executives manufacture an explanation for why they like something and then adjust their true preferences to suit that explanation.

TV execs, whether or not TV writers care to admit it, are human and are thus susceptible to the tenets of social psychology.

Let me be clear. My TVCruncher cannot predict how successful a pitch will be once it hits your television set. But I think it can predict which pitches are most likely to get to air in the first place, and, in doing so, it can save companies a ton of wasted cash. On average, of all the scripts purchased every year by each broadcast network, more than half have a minimal shot of success right out of the gate. The money that went into these sunk investments -- and the produced pilots that cost millions to shoot but will never see a television set -- instead could have been redirected towards projects with better odds. Research needs to be brought in earlier. It needs to be at the forefront of TV development.

One may think this system stymies creativity. In actuality, outside-the-box ideas like LOST can do well in this system. This is not a system supporting only formulaic shows like Law and Order. As president and CEO of CBS Corporation Les Moonves insists, each successful TV series contains similar elements. We're just breaking those elements down scientifically at the pitch stage. As an example -- I'll give you a couple and save more for later -- you may think a writer's track record, one component of the algorithm, doesn't matter. Just because a writer's previous dozen pilot scripts never resulted in a single show doesn't mean her next script can't as her writing is fantastic. Wrong approach. In what other industry does one's track record not matter when you're investing your company's fortunes? Are there writers who hit a homerun after years of selling scripts that go nowhere? Yes. Hi, Marc Cherry of Desperate Housewives fame. But re-watch He's Just Not That Into You. Cherry's the exception, not the rule. He's Ginnifer Goodwin.

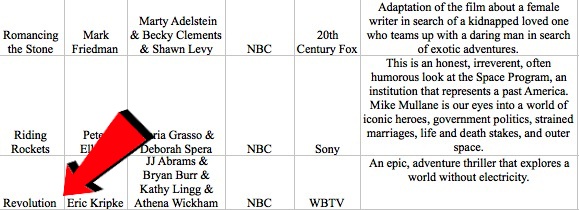

You've probably heard of Revolution, but chances are slim that you've heard of Riding Rockets. There are so many data points to mine with every television pitch. TV execs have been ignoring pertinent data for years.

Another example? Basing a pitch on source material like a book, foreign format, or movie improves its odds of getting to air. Oh yes, it matters, as Nellie Andreeva of Deadline Hollywood astutely points out in her analysis of the current pilot season. But what folks may not realize if they don't comb through the data of thousands of projects over the course of many seasons -- as I have done -- is that source material has mattered all decade. And certain types of source material help significantly more than others. Nellie will undoubtedly write about the importance of underlying source material next year as she did in 2011.

Just as data-driven analytics has been applied to baseball, finance, education, medicine, and, yes, feature films, it, too, can be applied to TV to remarkable success. It's a business calling for a new standard operating procedure. It's a business calling for a system of checks and balances. This system will not replace subjective thinking -- just complement it. If execs don't like an idea, don't do it. But if they like an idea and the data says otherwise, don't do it either. They should only pursue an idea if they like it and the data supports their intuition.

Malcolm Gladwell wrote, "The best and most successful organizations of any kind are the ones that understand how to combine rational analysis with instinctive judgment." Smart guy. But even more interesting is what the president of ABC Entertainment Group, Paul Lee, said in his first public remarks at the Alphabet: "If you don't look at your research then you're not understanding your network." He's exactly right.