- A film in which an animal plays a key role in a person's life (Lassie Come Home, My Friend Flicka, Free Willy, The Water Horse:Legend of the Deep).

- An animated film in which an anthropomorphic approach to the animal kingdom has given the animals human characteristics (The Lion King, Finding Nemo, The Jungle Book, Kung Fu Panda, My Dog Tulip).

- A nature documentary or Animal Planet series like Meerkat Manor or Orangutan Island, which follows a specific group of animals through the lens of human observations.

Watch the following trailer for Turtle: The Incredible Journey, and you will be keenly aware of the voice of the narrator (Miranda Richardson) and the film's lush, symphonic score.

Two recent nature documentaries went the extra distance by presenting the cycles of nature without the assistance of a musical score -- or any snappy theme songs -- to manipulate the audience's emotions. Most of the sounds heard throughout each film came from the animals themselves. The results are fascinating.

* * * * * * * * * *

The opening moments of the nature documentary directed by Nina Hedenius can be a bit disconcerting. It's a dark, snowy afternoon on a Swedish farm. Trees, houses, and barns are draped in deep layers of snow that bring a quiet hush to the area. As the camera moves silently around the landscape, one begins to wonder if there is something wrong with the film's soundtrack.

Or if there is one.

However, as soon as the camera enters one of the farm buildings, the audience hears the familiar sound of cows mooing and embarks on a journey that will follow the natural life of a farm through the four seasons of the year. As Way of Nature progresses, colts and calves will be born, cows will be milked, butter will be churned, and fences mended. The only time human voices are heard are during televised newscasts, a recording of traditional Swedish music, a brief passage of solo singing, and the muffled voices of the farm workers as they go about their work.

As the year progresses, Way of Nature unfolds before the audience like a tone poem in which horses, roosters, and goats are seen doing what comes naturally while the farm's dogs cuddle up beside their humans and monitor their daily chores. Watching intently as eggs are collected, cows receive their cowbells, and livestock is moved from one pasture to another, the dogs never tire of monitoring the local spectacle. Nor do the flowers or animals ever lose their beauty (the camera's attention to the detail of a rooster's feathers becomes a meditation on the brilliance of nature's art).

I always find it interesting when watching documentaries like Way of Nature to observe the audience's emotional reactions (often quite joyous) as animals behave like animals, unintentionally provoking laughter and satisfaction from onlookers they will never meet. Throughout the film, the constant cacophony of farm life becomes a symphony of bells, baas, and bleats -- of groans, grunts, and glissandi -- as the animals routinely meet, mate, and munch.

Way of Nature is the kind of documentary that requires enough patience to sit back and watch nature in action, to abandon the pretenses of modern civilization, and just listen to the beauty of the beasts. It is the kind of film where man's ego is minimized, and the animals dominate (without the slightest need for anthropomorphic cartoon characters). By the time winter skies start to darken and snow once again blankets the farm, the audience feels strangely charmed and reassured about the cycle of life.

Save Way of Nature for one of those special nights when you're cold, lonely, or depressed. Its simple magic provides a wonderful, warm tonic for the soul. Here's a brief trailer:

* * * * * * * * * *

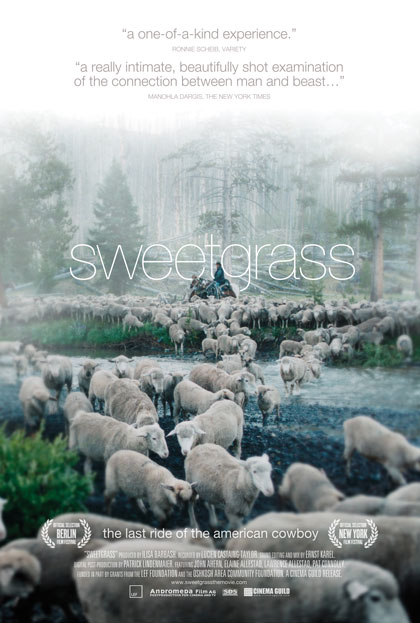

Sweetgrass is a magnificent film whose cinematography alone is worth the price of admission. Back in 2005, when Brokeback Mountain was all anyone could talk about, I found myself less entranced with Heath Ledger's portrayal of the closeted, butch Ennis del Mar and more attracted to Jake Gyllenhal's portrayal of rodeo cowboy Jack Twist.

However, if the truth be told, I was much more interested in the sheep. Apparently, I was not alone.

A documentary of unspeakable beauty, Sweetgrass follows the last group of modern-day cowboys as they lead their flocks of sheep up to their summer pastureland in the Absaroka-Beartooth mountains of Montana. This is the kind of nature film that, after 100 minutes of listening to sheep bleating, dogs barking, cowboys cursing, and wolves howling, leaves its audience begging for more.

In his recordist's statement, filmmaker Lucien Castaing-Taylor writes:

We began work on this film in the spring of 2001. Living at the time in Colorado, we heard about a family of Norwegian-American sheepherders in Montana who were among the last to trail their band of sheep long distances -- about 150 miles each year, all of it on hoof -- up to the mountains for summer pasture. I visited them that April during lambing, and was so taken with the magnitude of their life -- at once its allure and its arduousness -- that we ended up working with them, their friends, and their Irish-American hired hands intensively over the coming years.

Sweetgrass is one of nine films to have emerged from the footage we have shot over the last decade, the only one intended principally for theatrical exhibition. As they have been shaped through editing, the films seem to have become as much about the sheep as about their herders. The humans and animals that populate them commingle and crisscross in ways that have taken us by surprise. Sweetgrass depicts the twilight of a defining chapter in the history of the American West, the dying world of Western herders -- descendants of Scandinavian and northern European homesteaders -- as they struggle to make a living in an era increasingly inimical to their interests.

Set in Big Sky country, in a landscape of remarkable scale and beauty, the film portrays a lifeworld colored by an intense propinquity between nature and culture -- one that has been integral to the fabric of human existence throughout history, but which is almost unimaginable for the urban masses of today. Spending the summers high in the Rocky Mountains, among the herders, the sheep, and their predators, was a transcendent experience that will stay with me for the rest of my days.

Producer Ilisa Barbash has an equally intense recollection of how the film was made:

I am the last guy to do this and someone ought to make a film about it. So spoke old-time rancher Lawrence Allested in 2001, about the fact that he was the last person to drive his sheep up into Montana's Absaroka-Beartooth mountain range on a grazing permit that had been handed down in his Norwegian-American family for generations. As filmmakers and anthropologists living at the time in Boulder, Colorado, we had wanted to make a film about the American West and were instantly intrigued by the topic.

We drove up to Big Timber that summer, ready to make a film called The Last Sheep Drive. Our cars were loaded to the brim with three camera rigs, a bunch of radio microphones, our two kids, a dog, and a babysitter. For the first few weeks we'd wake up at 4 a.m. to help drive the sheep through town and then up the roads towards the hills. It was a family adventure for us, and a family enterprise for the ranchers -- with kids, grandparents, neighbors, and passers-by all helping.

It soon became clear, however, that because of the growing grizzly bear and grey wolf population, taking the kids up into the mountains would be impossible. So Lucien went up without us, hiking and riding, while I filmed other events in town -- rodeos, dog trials, shooting contests, haying, the Sweetgrass County Fair.

When Lucien got down from the mountains that fall, he was unrecognizable -- bearded beyond belief, 20 pounds lighter, carrying a ton of footage, and limping. He would later be diagnosed with trauma-induced advanced degenerative arthritis (caused by carrying the equipment day and night) and need [sic] double foot surgery.

When we started to watch the footage, we realized that we had two or more different films (and so many different points of view that I thought about calling the film A Piece of the Big Sky). We decided the most compelling story for a theatrical film was the original one we'd been interested in: the sheep drive itself -- as ritual, as history, as challenge. Even then, we had a good 200 hours of footage to wade through. Little did we know that this would take us about eight years.

In the meantime, we went back up to film lambing, shearing, the following year's sheep drive, and the one after that. We even moved to the East Coast. (We started joking that we'd call the film, The Penultimate Sheep Drive.) Most of the footage, however is from that first summer. In 2006, the ranch was sold along with most of the sheep. Now the film is finally finished.

As for a title, we'd started using Big Timber, as it was the name of the town where the drive began, but as fitting as that was for the title of a Western, it implied a film about logging. We finally settled on Sweetgrass. While the journey is tremendously hard, it is undertaken not just for the literal goal of reaching (sweet) grass, but also to carry on tradition against all sorts of odds.

There is a silent 1925 documentary called Grass: A Nation's Battle for Life by Merian C. Cooper, Ernest Schoedsack, and Marguerite Harrison, about an heroic seasonal trek (transhumance) of herds and Bakhtiari herdsmen in Persia. Sweetgrass tips its hat to that film, and is a tribute to past and contemporary people who still manage to eke out a bittersweet living on the land.

Whether its shots of sheep are by the dozen or clustered by the hundreds, Sweetgrass has a panoramic sweep whose natural beauty makes the best CGI scripting seem almost inconsequential. From the earliest parts of the film -- when each sheep gets a buzzcut -- to its final moments, Sweetgrass is a sheer (as well as shear) delight. Here's the trailer:

To read more of George Heymont go to My Cultural Landscape