The essay below is adapted from my book, "East Eats West: Writing in Two Hemispheres."

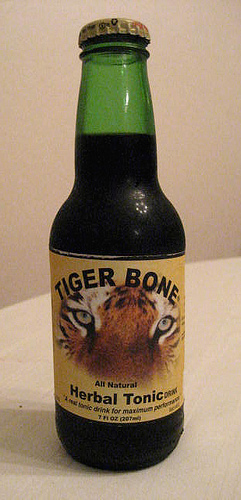

Many years ago when I was a frail asthmatic child living in Vietnam during the war, my great-aunt gave me a broth made of tiger bone. She promised it would turn me into a robust boy. My mother, a great believer in ancient remedies, readily consented.

"You are lucky," Great-Aunt told me, as she poured the steaming black broth into a bowl. "With all the bombings, there aren't that many tigers left in our country. You, boy, might be drinking the bones of the last one."

I watched the soup billowing smoke in front of me, and felt as if I was about to swallow poison. To make things worse, the tiger was my favorite animal and I was certain I was wholly unworthy to receive such a sacrifice. But a Vietnamese child is obedient; I wept, but I drank.

The broth was full of herbal smell, its bitter taste suggesting 1,000 wiggly jungle things. Half a dozen bowls of tiger bone soup followed over the next few weeks, but I continued to wheeze and heave and cough. Then Great-Aunt ran out of tiger bone and the treatment mercifully ended.

My asthma went away a year or so after I reached puberty in America. But a different kind of malady remains to this day, made up of guilt and the feeling that my fate is somehow intertwined with the fate of the tiger.

There are less than 6,000 tigers still living in the wild worldwide -- most of them in South Asia and disappearing fast due the encroachment and poachers -- and I have this strange, if unreasonable, feeling that when the last one goes, maybe so will I.

Perhaps it came the moment the dark broth passed my lips; or because I was born in the Vietnamese year of the cat. Perhaps it had to do with the hundreds of stories I heard as a child about long ago, when the Vietnamese people lived at the edge of an immense jungle, where a tiger ruled.

Country people, in fact, often call the tiger "Grandfather," rather than using its proper name, for many believe their ancestors' spirits sometimes take residence in wild animals.

Our old houseman, Uncle Cam, claimed the peculiar bald spot on the side of his head was "a gift from Grandfather." As a teenager, he told us, he often went foraging in the forest near Hue, the imperial city, and one day he crossed paths with a fierce tiger. Uncle Cam dropped to his knees, threw away his axe, and begged for his life. Moved by his eloquence, the tiger spared him and marked him as a relative, someone not to be eaten, by licking the side of his head. Uncle Cam's hair promptly fell off, and never grew back.

Even if I grew to doubt his story, I nevertheless felt a sense of camaraderie with the old man. Both of us, I felt, were deeply marked by the ruler of the dark forest, and would live beholden to his spirit and generosity. Of course this sentiment is neither rational or logical, but neither is the human relationship with wild beasts. Indeed, it is primitive and full of superstition -- we burden wild animals with all sorts of human characteristics and fantasies, and slay them because we covet or fear what we think they represent. The lion is courageous, the snake evil, the owl wise, the rhino is sturdy and invulnerable, the fox cunning and the tiger -- the tiger, above all -- is majestic, elegant, full of prowess and grace. It inspires awe.

Alas, the tiger's grip on our imagination is precisely the very force that drives it toward extinction.

Asia, where the great cats once roamed, is no longer a region of dark jungles and steppes and folklore. Soon, I suspect, there will be nothing to fear "in the wild" anymore because there will be no more "wild" anywhere. The tiger loses not only its habitat, but demands for its bones and skin as a cure or as fashion statements remain at an all-time high.

In Vietnam, where the tiger also once roamed, the forest is shrinking at an alarming rate. According to the United Nations Development Program Today one third of Vietnamese depend solely on forest and forest products for their living, and the number is rising.

The way things are going, I doubt I will ever run across a tiger the way Uncle Cam did, except in its many parts: skin, bones, dried penis, made into balms, wines, and pills and sold at specialty shops in Hong Kong, Saigon, Bangkok and Taipei.

It used to be that Vietnamese, unlike westerners, viewed people as inseparable from nature. They taught their children to revere the spirits that protected forests and rivers and often named their children after forest animals. Buddhist temples were not only places of worship but also where one is taught the ecological balance between man and nature.

But that was a long time ago. My Great-Aunt was a good-hearted woman but she was not sentimental about tigers -- if the last one goes, well, it was a matter of good fortune that its bones should help her precious great-nephew. Alas, I fear hers is a popular sentiment that hasn't changed much despite the advent of much more effective western medicines such as Viagra for aphrodisiac and propecia for hair growth and so on. If anything, the rarer the remedy the higher the demand. With mass consumerism in Asia coupled with deforestation, there's very little chance for the tiger and, for that matter, the rest of wildlife.

The only wilderness left is within; humans have conquered everything but themselves. We have decided, in the age of global warming, that we are our greatest enemy, our own stalker, and ultimately, our own destroyer.

The way things go, few in the world will ever see a real tiger in the wild anymore, but those kept in zoos and nature is what we call a "reserve." Instead of that "fearful symmetry" that William Blake immortalized in his poem "The Tyger," which might have once burned bright in the forest of the night, but has since been replaced by Tony, a child-friendly cartoon version who peddles cereal on TV with the innocuous jingle, "It tastes Grrrrreat!"

A while back in a Buddhist temple in Saigon, I saw a little boy tracing a bas relief of exquisitely carved dragons and tigers with his little fingers. "Mama," he asked, "does the tiger really exist, or is it just like the dragon?"

His mother answered with a sigh. "It is still real, but maybe not for very much longer."

"How come?" he asked.

But the boy's mother just shrugged.

I, of course, knew the answer. I and the others have have swallowed it, and tried as I may to regurgitate, all there is left of that poor, beautiful beast is a bitter aftertaste.

Andrew Lam is an editor with New America Media and author of "Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora," and "East Eats West: Writing in Two Hemispheres." His latest book is "Birds of Paradise Lost," a short story collection, was published in 2013 and won a Pen/Josephine Miles Literary Award in 2014.