LANSDALE, Pa. -- One midnight in April, Sabrina Malik pulls her red Chevy Blazer into her mother's asphalt driveway, removes the keys from the ignition, and stops to take a deep breath.

Alone in the darkness, a sense of defeat courses through her body -- disappointment about her past and uncertainty about what lies ahead. This, she thinks to herself, is surely what failure feels like.

Six years ago, Malik fled this town for Syracuse University. Since graduating in 2009 with a bachelor's degree in art history, she has yet to find a decent job.

She hadn't planned on moving back home and, at the age of 23, never expected to return to her mother's house for an extended and open-ended period of time.

"At times, it really feels very personal, it really feels like I've failed," says Malik, standing in the kitchen of her mother's two-story stone house and recalling the eight weeks since she returned home. She's wearing khaki shorts and white socks that come up to her ankles. Glasses frame her brown eyes and wavy chestnut hair grazes her shoulders. "Your dream is a very personal thing and when you can't do it, it feels like you're being told that you're not talented enough and that you haven't worked hard enough."

After graduating from college, Malik moved to Boston. There, she worked as a nanny, sold books, and waited tables -- a series of dead-end jobs that didn't pay more than the minimum wage, didn't require a college degree, and weren't remotely related to what she wanted to do for the rest of her life.

Two months ago, she ran out of money and drove home from Boston to Lansdale, a middle-class suburb north of Philadelphia, her car brimming with the contents of post-college life: canned food, twinkle lights, potted plants. A dozen of her paintings, stacked to the ceiling, kept hitting the back of her head. When a gas station attendant in New Jersey asked why she was moving and where she was headed, Malik didn't know quite how to respond.

She's hardly alone. Malik is part of a generation of 20-somethings that's experiencing what it's like to graduate from college, move back in with your parents, and then get stuck there.

To be sure, having a college degree still matters. Nationwide, while the unemployment rate hovers around 9 percent, the jobless rate for college graduates 25 years and older is 4.5 percent. By contrast, 20 to 24-year-olds who only have a high school diploma are contending with an unemployment rate of nearly 20 percent.

While college graduates typically navigate periods of economic decline far better than those lacking such credentials, the past few years have still taken an especially brutal toll on them. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the jobless rate for younger workers with a college degree has more than doubled since the recession began four years ago -- from 3.5 percent in April of 2007 to 6.4 percent in April of this year.

For college graduates under the age of 25, finding stable work is a particular challenge. According to Andrew Sum, an economist at Northeastern University, about half, or 3.2 million, are "underutilized" -- meaning they're unemployed, working part-time, or working a job outside of the college labor market, such as bartending or waiting tables.

Added to the lack of jobs is an increased amount of debt. Student loan debt recently outpaced credit card debt in terms of total amounts owed by borrowers. By year's end, it is on track to surpass a trillion dollars, according to Mark Kantrowitz, an expert on student financial aid who runs the websites FinAid.org and Fastweb.com.

According to the Institute for College Access and Success, an independent, nonprofit organization that works to make higher education more affordable, the average graduate finishes school with $24,000 of debt -- though many struggle to repay far more.

Like Malik, many 20-somethings are experiencing early adulthood as one long pause in their lives, affecting not only conventional coming-of-age milestones such as becoming financially independent, but more deeply personal things as well -- like their hopes and their dreams.

THE AMERICAN DREAM

Recently, after sending out dozens of resumes and cover letters, all of which went unanswered, Malik's spirits plummeted. Even rejection feels better than no response at all, she thought to herself.

In her second-floor bedroom, where handmade quilts cover the bed and charcoal drawings line the walls, she tries as best she can to avoid her mother's notice. Mostly, she just doesn't want her to worry.

But Marilyn Malik is close to her daughter and is an expert at reading Sabrina's shifting moods.

"Sabrina gets down on herself and I worry," says Marilyn, sitting in her home office in the basement, where she works as a nursing supervisor for a health insurance company.

While she says that her daughter is welcome to live in the house for as long as she needs, she hopes that Sabrina might find a job sooner rather than later. And Marilyn is adjusting to the fact that her daughter's path may not mirror the one she took 30 years ago, when, as a college-educated young woman, she first ventured out into the world.

Marilyn, 53, grew up in a small town in the Poconos. Her father worked as an electrician; her mother worked as a nurse. Marilyn studied nursing in college and she and her parents split the $4,000 annual tuition. She worked as a waitress to earn her share.

A few years after college, Marilyn married Ajmal Malik, a Pakistani immigrant. He attended college at the University of Lahore in Pakistan and earned two master's degrees after moving to the U.S. The couple made their home in Plymouth Meeting, Pa., where they raised Sabrina and her older brother Omar, who's now 25.

In those early years, Ajmal, an accountant, worked his way up the ladder while Marilyn picked up night shifts at the nearby hospital. She describes their standard of living as lower-middle-class -- borrowing money to purchase their first starter home and relying on quick, cheap dinners of soup and biscuits to get by.

Ajmal died of cancer when his children were nine and 11, leaving Marilyn to support an entire household on her income alone. "You grieve for yourself, and you grieve for your kids," explains Marilyn, who started working full-time after Ajmal died and has yet to let up.

Sending both kids to college was always the plan. The majority of the payout from her deceased husband's life insurance went towards a college savings account, which ultimately wasn't enough to cover the high costs associated with sending two kids to out-of-state schools. Marilyn paid about $100,000 for Sabrina to attend Syracuse University in upstate N.Y. and took out another $20,000 in loans to cover the rest. Sabrina and Omar, who attended the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, will have to shoulder their own graduate school costs, however.

"She'd probably say no to doing things if she knew how much everything cost," says Marilyn, who pays down the $20,000 in Sabrina's student loans while also saving up for her own retirement.

Sabrina is struggling to pay off about $2,000 in credit card debt and her remaining student debts weigh on her relationship with her mother. Marilyn hates owing money and tries to put an extra $100 or $200 towards paying down the student loans whenever she can.

Marilyn and Sabrina find it hard to talk about Sabrina's student loans and generally avoid the subject. Sabrina wishes she could do more to help her mother pay the debt and had planned on having a job after graduating that would allow her to do that -- yet another part of her future that hasn't exactly gone as planned.

While living in Boston, she made barely enough to cover her own rent and utilities, let alone scrape together enough extra to help her mother with the monthly loan repayments. Sabrina also wonders whether paying so much for college has made her mother's own life more insecure.

"I know she's further away from her own retirement because she sent us to such expensive schools" says Malik, whose plans for graduate education are indefinitely on hold until she can save up some money. Right now, even $80 application fees for graduate school seem like a lot.

Although Marilyn remarried a few years ago, her first husband's absence is deeply felt -- especially now, when their daughter is struggling. "I wonder if he had been around, whether my kids would have been better placed, whether they would have received better advice," says Marilyn, who plans to work for at least another decade. She long ago decided that sending her kids to college was more important to her than saving for the day when she could retire.

By this point in her life, Marilyn imagined that her daughter would have already embarked upon a well-paying career and be living on her own. She also wonders what it means for the next generation of 20-somethings, and whether they'll have access to better opportunities than their parents' generation.

"My generation had it better than what my parents had and you'd think it would continue progressing that same way," she says. "Historically, each generation gets better as it goes along -- they're more affluent, they have more education, they reach more goals. This generation, you would hope that would happen, too, but it doesn't seem to be going that way."

DREAMS ARE CHEAP

Half a century ago, 77 percent of women and 65 percent of men had attained traditional markers of maturity by their 30th birthday: They had left home, finished school, gotten a job, married, and started a family. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, by 2000, less than half of 30-year-old women and just one-third of 30-year-old men had attained similar markers of adulthood.

A lot, but not all, of the shift has to do with work -- or, more specifically, a lack of work, say analysts and others. They argue that the current recession has pushed 20-somethings farther and faster in a direction they were already headed.

Sending your kid to college once was a way of ensuring their sure-footed success. But with 20-somethings mired in debt and confronting a dearth of decent-paying jobs, many are returning to the nest.

"I can assure you that few people in my generation are living high off the hog in their parents' house," says Matthew Segal, the 25-year-old founder of Our Time, a national membership organization for young people under 30. He says he resents the popular characterization of 20-somethings as lazy and unmoored. "Trust me, they're not getting too comfortable sleeping in their childhood bedroom or eating out of their parents' fridge. They're moving home because they don't have jobs and they have a lot of debt."

Except for designated downtime, when she's either making art or weaving on her loom, Malik spends much of her time avoiding thinking about what became of the goals her parents helped her to set. Her mother always encouraged her to think and dream big. Yet since graduating from college, she's found herself doing the exact opposite.

Her dream for the future used to encompass a well-appointed and comfortable life -- a farmhouse, two artist studios, a husband, and several children. "But it's not worth dreaming so big anymore," says Malik. "My plans now are far less extravagant. I guess I'm learning to dream on a much smaller scale."

Specifically, she doesn't think she'll be able to afford a home as nice as her mother's. Nor, she predicts, will she be able to send her own children to schools as fancy as those that she attended.

"The hope that things are going to get better is really all we have," she explains. "I mean, on top of being the generation that's struggling, we don't want to be the generation that's cynical, too."

Some scholars attribute such hard-wired optimism to the way that the parents of 20-somethings raised them. Morley Winograd and Michael D. Hais co-author books about millennials (typically defined as the generation born between 1982 and 2003).

"Millennials were raised the way Bill Cosby told parents to raise their kids -- set rules, show encouragement, don't use physical discipline, build up a child's self-esteem," explains Winograd. "If you tell someone from zero to 13 that they're always doing a nice job and that they're really special and wonderful, they'll wind up believing they are."

Self-confidence breeds optimism, according to Winograd and Hais, even when times are tough. "The millennials don't have a sense that everything is wonderful, because obviously it isn't, but they believe as a country that things will get better and their lives will also get better," says Hais. "In part, it's because they're young and they actually have time to accomplish this. But it's also because generations like the millennials feel they've accomplished good things in the past and that they will again in the future because their parents told them so."

Jeffrey Jensen Arnett, a psychology professor at Clark University, is also struck by the optimism of the young adults that he studies. "I think the main reason for their optimism is that dreams are cheap in emerging adulthood. That is, their dreams haven't yet been tested in the fires of real, adult life. And who knows, maybe they really will find their dream job?"

In general, young people are taking longer to assume more traditional adult responsibilities and young lives are unfolding in a less predictable sequence, Arnett says. He views the twenties as a new and distinct life stage and classifies it as "emerging adulthood."

According to Arnett, this stage generally starts around the age of 18 and continues until an individual is in his or her mid-to-late twenties. While the category itself is fluid, "emerging adulthood" refers to a time during which young people are relatively free of obligations. But many 20-somethings, like Malik, are increasingly delaying adult responsibilities because they can't secure a job stable enough to allow them to take the steps necessary to establish an independent life.

As such, even youthful optimism has its limits. Despite a general proclivity toward positive thinking, analysts say current circumstances are weighing down this generation of 20-somethings.

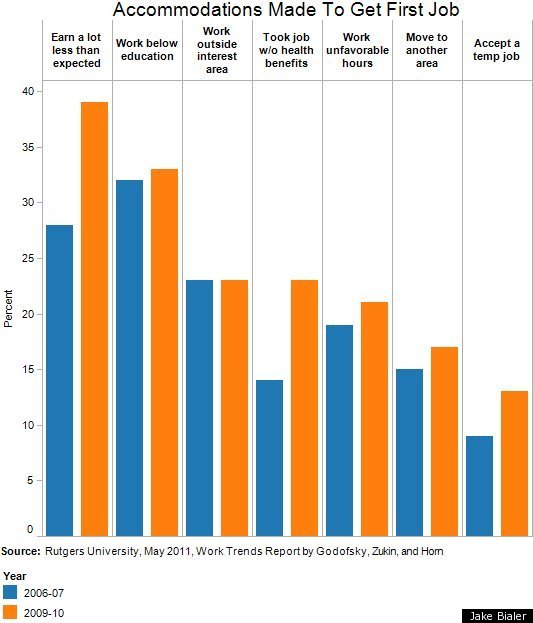

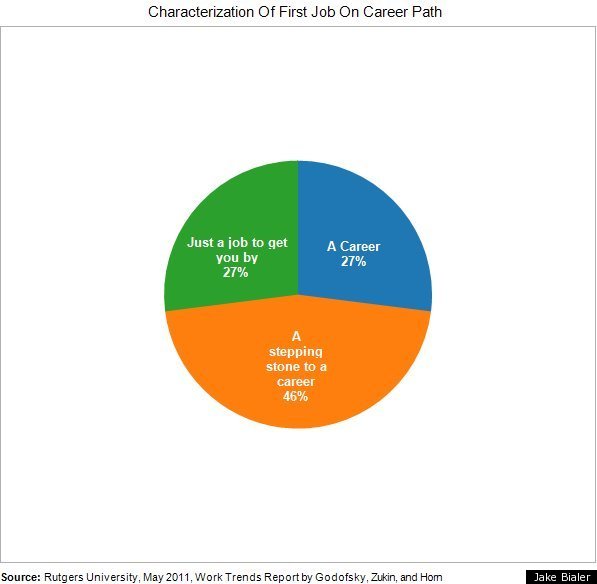

"The mood for young people definitely isn't as optimistic as it's been in the past," says Carl Van Horn, a professor of public policy at Rutgers University. Last week, he and his colleagues released a study titled "Unfulfilled Expectations: Recent College Graduates Struggle in a Troubled Economy." It polled young people who graduated from college between 2006 and 2010. "You expect people to be optimistic when they're young about their ability to get ahead," Van Horn says. "It's pretty clear that this group of college students are feeling very much like their opportunities have been stunted."

A FALSE PROMISE?

Since moving home, the highlight of Malik's weekend involves walking to the edge of her mother's driveway on Sunday morning and retrieving the hand-delivered copy of The New York Times. She's on a $15 weekly budget and getting the paper delivered is a rare indulgence.

Last Sunday, Malik accompanied her extended family to a pancake breakfast to support the local firehouse in the nearby town of Sellersville, Pa. Without traffic, it's about a 20-minute drive from Lansdale.

As her family and some of her mother's friends waited for a table, Malik carved out a tiny space where she sat and read the paper in silence. She wasn't up for answering the questions that usually follow -- about what she was up to, or how the job search was going. She mostly just needed a break from the constant inquisition.

"I spend a lot of my time trying as best I can to appease everyone and show them that I'm in good spirits and putting forth all this extra effort," says Malik. "Every once in a while, I just need to be by myself. They know what I'm going through."

Even the relentless optimism of millennials is straining under the depth and length of the current recession. A poll released in April by AP-Viacom indicated that among Americans between the ages of 18 to 24, there was skepticism about the notion that life would improve with each passing generation. Four in 10 of those surveyed predicted difficulty in raising a family and affording the lifestyle they felt they deserved.

Like homebuyers who took on outsized mortgages they couldn't afford, either out of ignorance or because banks cajoled them, in order to realize the American Dream of home ownership, many students and their parents have taken on crushing piles of educational debt in order to realize another part of the American Dream: a college education.

Andrew Sum, a 64-year-old economist at Northeastern University who's studied the college labor market for the past 30 years, thinks the current economic slump is giving both recent graduates and their parents a rude awakening. Sum grew up in Gary, Ind. with a father who worked as a welder. While he says that he and his four siblings were able to achieve a better life than their parents, for the first time in recent American history, the majority of the young people he studies are not.

"Every generation ought to try and leave behind a better world for the next generation," says Sum. "And until recently, it's generally been true that the next generation exceeded the living standard of the current one. But over the last decade, that's no longer the case."

One of Sum's pet theories is the "age twist effect." He says that over the decade from 2000 to 2010, the younger someone was, the more likely they were to get fired or be otherwise left without a job. Historically, and in every decade since the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics began compiling such data, it's been the exact opposite. Sum's findings conclude that 7 million more young people under the age of 30 would be working today if the labor market behaved as it did only a decade ago.

Sum and his colleagues predict that underutilization and underemployment will leave an indelible mark on this generation. In the near term, Sum finds college graduates moving home, and staying there. And while college degrees matter, they only matter if young people are able to then convert them into a job -- hence, generating the considerable college premium.

"If you can manage to do that, you can do well," says Sum. "But if you end up outside, you'll only do marginally better than someone who has a high school diploma and those losses stay with you for a lifetime."

For Malik, both in terms of her current and future income, the longer she's out of work, the more dire the consequences will be. Being unemployed is always worse than working, but it's ultimately the type of job she gets that will affect her future stability. For instance, should Malik secure yet another job outside the college labor market -- working again as a nanny or as a clerk in a retail shop -- the chances that she'll regain a more permanent economic toehold will grow ever more unlikely.

The impact that the job she lands will have on her future wages is likely to be staggering.

For the public at large, Sum finds there's a 73 percent gap in the annual earnings of college graduates that have a college labor market job versus those that work in a job that doesn't require a degree -- say, the difference between working as a paralegal and a receptionist in a law firm. Bachelor's degree holders between the ages of 22 to 64 that have a college labor market job make an average salary of $52,873. Those working outside the college labor market earn $30,503 -- or a difference in salary of more than $22,000 a year.

But many 20-somethings, like Malik, are also struggling with what is likely a case of bad economic timing. Graduates of 2009 were hit especially hard. A study conducted by the John J. Heldrich Center for Workforce Development at Rutgers indicates that 50 percent of 2009 graduates are either unemployed or working in jobs that don't require a college degree.

Lisa B. Khan, who studies economics at Yale's School of Management, recently conducted a study that looked at the long-term impact of graduating into a weak economy. Khan examined young people that graduated from college during the peak of the recession that occurred in the 1980s. In their first three years on the job market, Khan found they made about 30 percent less than classmates with more advantageous economic timing. And their subsequent salaries, even a dozen years later, were between eight and ten percent lower.

This means that it might take Malik, who graduated two years ago during the beginning of a particularly brutal recession, up to a decade to recover the wages she might have earned had she sidestepped the downturn altogether.

Paul Oyer, an economist at Stanford University, concedes that young people who start work when times are tough not only get behind, but generally have a tough time catching up. But Oyer also thinks that luck plays a role in the making of any successful career, good economic times or bad.

What does concern him is that some historical trends seem to be withering in the current economy. Although wealth in America has increased from generation to generation, Oyer isn't convinced that the current generation of 20-somethings will enjoy the rewards of a similar phenomenon. He attributes the shift to globalization and the number of available jobs. Because of these factors, he doesn't think it makes much sense for young people to pile on educational debt to attend elite schools when they have less expensive alternatives -- unless, of course, their parents are willing to go on the hook for it.

Parents exert a powerful shaping force on their children's decisions to go to college, as well as which college to attend. In addition, they are often caught up in the emotional rush that a college education entails, further complicating an issue that has already become a financial minefield for the middle class.

"All along, I was going to make it work," explains Marilyn. "If I had to take out loans, I was going to do that."

Once Sabrina and Omar were admitted into the colleges of their dreams, Marilyn saw it as her personal responsibility to make sure they could attend -- even when it meant taking out additional loans in order to finance it. And while Marilyn says she doesn't regret her investment, she assumed that a $120,000 degree would at least translate into a decent-paying job for her daughter.

"One thing that terrifies parents more than budget deficits or a weak economy is job security for their kids. They're afraid they won't be able to pass along their middle class status to the next generation," says Anthony P. Carnevale, who directs Georgetown University's Center on Education and the Workforce. "In raising a child in America, the fear of failing is just enormous. Sending your kid to college used to pretty much guarantee their future success. It no longer necessarily works that way."

And, of course, what if this generation simply doesn't value the same things their parents' generation did? John Della Volpe, who directs polling at Harvard University's Institute of Politics, spends much of the year gauging the thoughts of young people. His company SocialSphere recently conducted a study of 5,000 millennials between the ages of 16 and 24. It asked them to think about the next five to seven years of their lives and to rank the importance of what they hoped to achieve.

His findings indicate that many young people aren't focused on becoming famous or making piles of money. On the contrary, their hopes for the future revolve around making a contribution to society and staying in close touch with family and friends.

"There's a potential for this younger generation to have an economic reset," explains Della Volpe. "It's now okay to stay in your hometown."

AN UNCERTAIN FUTURE

When it's your decision, returning to your hometown is one thing. Being stuck there feels like something else entirely.

Malik says her days are an exercise in resilience. She has yet to shake her loneliness and general feeling of isolation.

Most weekdays, she gets up by nine o'clock and immediately forces herself to get dressed. After breakfast, she typically positions herself on one of two floral upholstered couches in the sunroom, where, with laptop in hand, she begins the daily chore of scouring websites for job openings.

When not job hunting, Malik helps out around the house -- taking out the trash, doing the dishes, going grocery shopping, walking the dog, or making dinner a few nights a week. In some ways, the chores remind her of being in high school. Before her mother remarried and she and her brother headed off to college, it was just the three of them helping out around the house. Growing up, when her mother made dinner or when the house needed cleaning, the two siblings alternated chores.

"Now that I'm back, I do those same kinds of things and it feels like the least I can do," explains Malik. "It doesn't feel like a task or a chore. I'm just helping my mom out, like I've always done."

But now, Malik is a grown woman. Part of her yearns for her own place where she can come and go as she pleases, and where the rules are hers and hers alone. On visits to see her boyfriend, who lives in Brooklyn, N.Y. and works for a private art collector, she sees glimpses of the independent life she expected to be living by now.

Until she can land her ultimate gig of working as a curator in an art gallery, or begin a long trajectory of jobs that might eventually get her there, she's looking for something to pay the bills. She's looked into working as a clerk in a local retail shop and selling hot water heaters.

Businesses in Lansdale are inundated with swarms of recent colleges graduates looking for any job they can get. Locally, there's the option of working for a big pharmaceutical company, Starbucks or Walgreens, but not much else.

When things start to feel overwhelming, Malik finds it helpful to make lists of things to accomplish. The current two-page iteration lists everything from big to small stuff -- like getting a job and someday opening an art gallery to straightening her hair and eating fewer bagels.

A recent addition, which has yet to be crossed off, is that Malik aspires to be less hard on herself. Namely, that for the time being at least, it's okay to allow herself to feel sad sometimes.

"Right now, it's a battle of trying to remain levelheaded -- and I don't know if it's trying to stay optimistic, or become more realistic, or just learn to be okay with going through the motions," she says. "It feels like a lot of pressure. I want to make everyone proud. I want to blow everyone out of the water with everything I've accomplished. And I just can't get there."

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story referenced a study that said 85% of college graduates are returning home to live with their parents. That statistic was picked up by reports in Time Magazine and subsequently in HuffPost. PolitiFact debunked the widely cited number. A Pew study in December 2011 found that "39% of all adults ages 18 to 34 say they either live with their parents now or moved back in temporarily in recent years," including 53% of those 18 to 24. While educational status didn't appear to impact living status for those under 30, it did make a big impact after that age. All of this is far better than the purported 85% of college grads returning home, but these number aren't exactly low. A sobering statistic from Pew: one-in-ten college educated adults between the ages of 30 and 34 are living at home.