I wasn't at all certain that I'd like the new movie that dramatizes "The Help," Kathryn Stockett's 2009 runaway New York Times bestseller.

Sure, the casting was first-rate. Fine black actresses Viola Davis, Octavia Spencer, Cicely Tyson, LaChanze and Aunjanue Ellis interpret roles of a stature that we have seldom previously had the opportunity to enjoy from them. White performers Emma Stone, Bryce Dallas Howard and Sissy Spacek, seemingly channeling Diane Keaton, were also exceptional.

Much of the movie is also laugh-out-loud funny, with the eye-rolling and antic gestures of Ms. Spencer and the campy cut-ups of Leslie Jordan, easily equaled by Bryce Dallas Howard's pathetic villainy. Yet some black cultural pundits still suggested that this film, in the tradition of "Imitation of Life" or "The Little Foxes," merely perpetuated a host of old harmful stereotypes.

What I worried about was something more sinister. Every African-American family, irrespective of relative privilege or wealth, has had members who worked as servants for whites. So I worried that the "Satan sandwich" of black servitude, so familiar to us, would be sugarcoated and trivialized beyond both recognition or utility.

What lives they led, our recent ancestors who worked in service! The hoops they had to jump through were never-ending, and expectations of their duties defy belief:

"I had to spend half my pay to get my new pea-green hat out of lay-away in order to feel better. I had scrubbed that lady's kitchen floor on my hands and knees, and she said, 'Louise, the floor is not clean. Do it again!' and I had no choice, I had to do the floor over."

These words belong to my grandmother, speaking of working in Akron, Ohio during the Great Depression. My mom's Aunt Cora, also living in Akron, in the North, had her stories, too. Like those of my father's great-grandmother, Mamma Emma, which had been related to Aunt Cora, the most chilling of their tales involved white men, the sons, husbands, relations and guests of the ladies for whom they worked.

"This was the North, but they simply assumed that, besides cooking, washing, ironing, serving, cleaning, shopping and taking care of children, you were also there for their pleasure!" Aunt Cora exclaimed at lunch, following my great-grandmother's funeral. She was reminiscing with a family friend who had worked for the Firestone family, but I'd taken in every word.

What wonderful lemon-coconut layer cakes Aunt Cora learned to make cooking for white folks! Her fruit cakes, aspics, Waldorf salads, lamb chops, chicken à la King and Lobster Newburg were wonderful, too. As an accomplished cook, Aunt Cora was always in demand, and several friends had fallen out when one, offering better pay and more time off, had "stolen" her from another.

"Married or single, old or young, these men, most men, were always pestering you," Aunt Cora told me when I was only around 5. "It was even worse in the South. That's how your Mamma Willie was born."

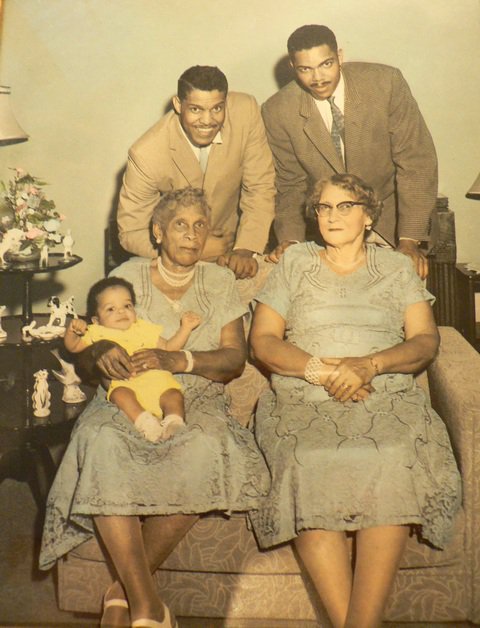

Willie Mae Adams, my great-grandmother, known as Mamma Willie; her mother, Emma Jones, known as Mamma Emma, who's holding me; Mamma Willie's son, Alexander Leroy Adams, Sr., who made the photograph and is standing behind her; and Mamma Willie's grandson, my dad, Alexander Leroy Adams, Jr. (1956)

With lank, silky, blonde hair and brilliant, china-blue eyes, Mamma Willie, my father's grandmother, looked white. She never worked as a maid. Her mother, aunt and grandmother each had, and so did both of my parents' mothers, but not Mamma Willie. Still, she was terribly race-proud, which meant that she was always shocking whites who'd just finished disparaging my dad during some track meet or other athletic contest, by informing them that he was her grandson and how proud she was of him.

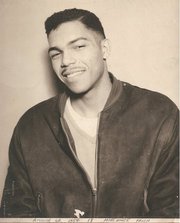

My dad, Alex Adams, during his abortive term at Moorehouse in 1952

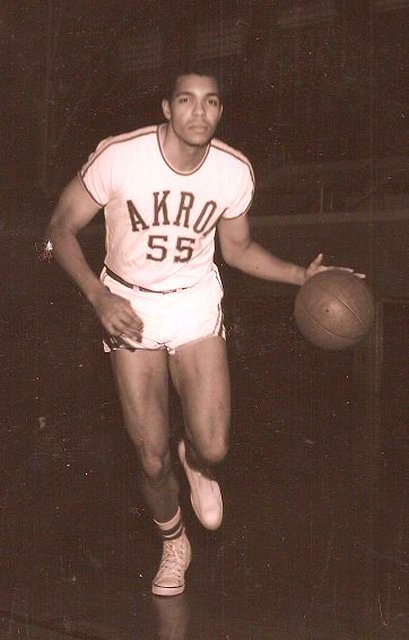

My dad on the basketball court at the University of Akron in 1961

Brought up on a steady TV diet of "The Flintstones," "Dennis the Menace" and "Leave It to Beaver," I, too, was taken aback one morning.

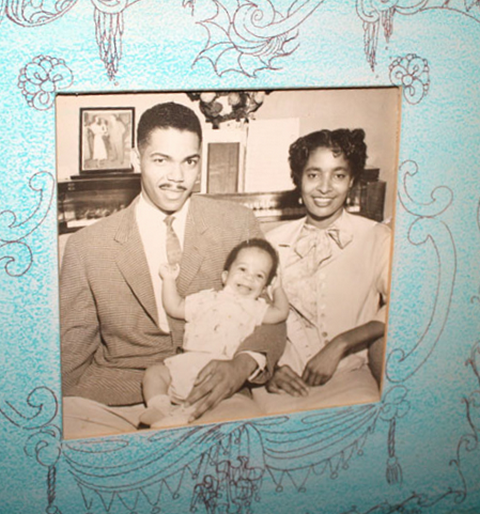

My family, the Adamses, Easter 1962

"Are you going to be my good little colored boy today, Mike?" Mamma Willie had asked me.

"No! I'm going to be your good little white boy!" I'd shouted back. But even at 4, I suspected that there was reason to be defensive about the position I was insisting upon. You see, this was my "doll test," and my loving and adoring Mamma Willie, who kept me whenever she could, was my white doll, emblematic of all that was good, true and lovely. Her house on Diagonal Road, with lush flower beds, a cast-iron-railed veranda, a picture window, a working fireplace and Duncan Phyfe reproductions, was the the grandest owned by any member of our family. Better than anyone else, she understood me. She had even defied my dad and given me a beautiful, yellow, toy washing machine, with a wringer that actually worked.

"But Baby, you're colored!" she said.

"No! I'm white, like you!" I implored, rejecting her absurd assertion.

"Baby, I'm not white, and neither are you!" she laughed, intending to defuse my hurt.

But even running home to the comforting arms of my brown-skinned mother, who, with tender patience, wiped away my tears, I'd sensed that Mamma Willie was really right. I was not, could not be, clever, cute or precocious like Dennis, Beaver or Oppie. Instead, just like other darker blacks, I'd have to become accustomed to being reviled and despised, dismissed as savage, ignorant, ugly or inept, like Farina, Buckwheat or the natives on "Tarzan."

My still-beautiful mom in 1956

It was this incident that had prompted my great-grandmother to reveal to me that her father had been a white man, that her parents had not been married. Just a few years later I contradicted my own negative expectations of unawareness. Exasperated, Aunt Cora, learning that Mamma Willie had taken me with her to visit one of her son's "outside" children, asked me, with outraged indignation, "What's wrong with your grandmother? Why is Willie always claiming these bastard children?"

"Maybe," I responded calmly, "it's because she's one herself?"

Stunned by the wisdom of the innocent, Aunt Cora was so impressed that she exclaimed, "Bless your heart! You're right. You're right!" Then, relating a story told to her years before by Mamma Emma, Aunt Cora shared with me the secret of Mamma Willie's white father. She started as matter-of-factly as if we were both 60, embellishing the basic story that Mamma Willie had already outlined.

At 18, Mamma Willie's mother, Mamma Emma, had waited tables for an Irish-American storekeeper in Columbus, Ga. But Mamma Willie had mentioned nothing about sexual imposition or rape. Aunt Cora, by contrast, conveyed a first-hand account direct from the victim. The young waitress was surprised as she walked home from work by her upstanding employer, 73 years old and the father of 12 white children, and mounted on his horse.

"Lie down over there in that ditch, Emma," he told her. "You know what you got to do."

Even as a child, utterly ignorant of sexual mechanics, I'd appreciated the enormity and wrong of what had occurred.

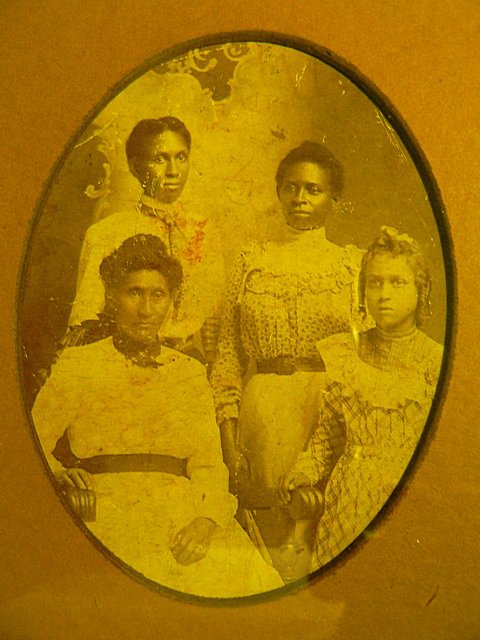

My great-grandmother Mamma Willie as a girl; her grandmother Bellamay; Mamma Willie's aunt Annie; and Mamma Willie's mother, Mamma Emma

One way or another, such encounters were a constant hazard for black servants, including the 14-year-old nursemaid mother of actress Edna Lewis Thomas, and Strom Thurman's 16-year-old maid/mistress Carrie Butler. Not bothering to acknowledge this particular menace, "The Help" fails to be all that it might have been.

Additionally, no one's black child, certainly not in the 1960s and probably not even now, would have ever antagonistically barged into the middle of a party where her mamma was serving lunch, thereby having her thrown out. Whether living in the North as a college-trained professional, or in the South as a laborer who had left school in the fifth grade, no black child would have ever been so clueless and even cruel, especially given that this character's mamma loved her white folks. Not even an Angela Davis would have done that.

However, neither this, nor the ahistorical untidiness of the white hero's hair, nor the movie's anachronistic use of rubrum lilies really matters. Powerfully, affectingly, this film tells a story many blacks and whites would rather forget, how black women stepped up and did what they must to survive. That's a story important enough to make all the story's faults, whether stylistic or more substantive, minor by contrast.

It's also a stranger tale, one about child-rearing and cultivating courage or encouraging hate, a story of the divided and often absent affections of one's parents or caregivers. How ironic that so many white children, those most intimately nurtured, even suckled and loved, by black second mothers still became virulently racist! But is that any different from misogynist sons, simultaneously resentful of and totally dependent upon women? What makes so many sons raised by my most fervently feminist friends so determined to get back at Mommy?

It's been suggested that, in time, Thomas Jefferson came to view miscegenation as the ultimate solution to America's race problem. Perhaps, in centuries to come, he'll be proven right, but thus far, mixing races has been a mixed blessing at best: in some cases it's been a curse whereby certain mixed blacks, coming to believe that education, achievement and social class trump race, routinely lord it over their less privileged, darker brethren. Of course, embracing the fallacy that anything short of actually "passing" can accord the status of being regarded as an honorary white person is sure to bring on disappointment, too.

What makes the persisting higher status offered mixed-race blacks specious is the way it unavoidably reinforces the deceit of white superiority. All the same, like so many lies, it can be an alluring deception. Even as one comes up against its limitations, it can beguile one insidiously. Sooner or later, limitation upon limitation, following the illusion of possibility and promise, that mind arrangement begins to take its toll.

For my friend Marguerite Marshall Blake, who was well practiced at emphasizing the positive, "mulatto," as she might have been characterized on the 1930 census, was never "tragic."

She died last week, at age 90. A recipient of plenty of woe, she always embraced joy. One poignant expression of her deep affection toward me occurred not long after we met in the late 1980s. Aware that I was gay but unattached, aware even that I was lonely, she urged, "You might consider getting married, to a woman. I know that you are gay, but lots of gay men have done this. You're so charming, intellectual and elegant, many woman would find you a great catch, and you like children... you'd make a wonderful father..."

Some people are heroic or become famous because of their wealth, their jobs, their husband or their children. The loving and devoted wife for over 40 years of groundbreaking African-American Harlem police detective Warren Blake, none of these factors applied to Marguerite. Apart from being a caring person toward friends and others who came to her for help, especially once a loved one had died, something else made her a notable person.

As a 16-year-old, Marguerite Marshall, who loved the movies, inexplicably, dreamed of helping make people beautiful. Her talented mother danced at the Cotton Club, but she wanted to become a plastic surgeon. Imagine a woman, an African-American woman, becoming a plastic surgeon in the late 1930s!

Marge also used to walk past the extraordinary, 30-room limestone house at 10 St. Nicholas Place, at the corner of 150th Street, built by circus showman James Anthony Bailey. With her Wadleigh High School friends, Nellie and Edith, she'd dream about what it would be like to live there. One day, she impulsively rang the bell and asked the owner, Dr. Franz Koempel, and his wife Bertha, if she could have the right of first refusal if the house was ever sold. Koempel was famous internationally as a pioneering X-ray specialist. A founder of the Steuben Society, he and his wife spent each summer at their villa in Bavaria.

Several years later a ''For Sale'' sign appeared on the Koempel's lawn, and Marge rang the bell again, reminding the owners of their promise. The widowed Bertha Koempel happily conceded that an understanding existed, but she insisted that any acquisition must also include two shingled houses north of hers, which had been acquired years earlier to protect the house's light and air. The asking price was $86,000, just $6,000 more than the house had cost to erect in 1888. It was an astonishing amount for most blacks of the period.

Marge, her husband and parents, who all worked, pooled their resources. ''There was a lot of scraping around and getting it together, but I got the house,'' she later recalled.

Marguerite Marshall Blake lived there from 1951 until 2007, operating a funeral home on the ground floor since 1955.

This was how one of New York's most extraordinary landmarks was saved from total destruction. Subsequently the Blakes were inundated by offers to buy their house, inevitably from whites. Warren felt that these prospective buyers were often motivated, at least in part, by a feeling that their house was "too good, too special for blacks to own."

This magnificent structure, then, is his and Marge's enduring monument. Thanks to them, generations not yet born will be able to enjoy this gift from our past to the future, and the true hero of this story, of course, is the beautiful, kind and ingenious lady, Marguerite Marshall Blake. All of us who knew her were blessed, and, through her foresight, she blesses everyone, forever!

Jane White, who grew up nearby at Sugar Hill's ultra-desirable Colonial Parkway Apartments at 409 Edgecombe Avenue, was yet another girl who, though never having to consider becoming a maid, nonetheless understood how much race matters. Indeed, the Whites' household, headed by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People's aptly named officer, Walter F. White, were among that distinct minority of blacks who themselves employed household help.

What was such affluence and advantage like during Harlem's golden age? I once called actress Jane White at her Greenwich Village apartment to ask for an interview. She was very accommodating, despite being politely reticent. Could I write her a note before we met to talk?

I never did, so my sense of loss learning that she died, age 88, a couple of weeks ago, was acute. Since then, I have learned that despite a host of steady roles on Broadway and TV and at cabarets, Ms. White felt cheated. Educated at Smith but too dark to be "convincingly" white, while regarded by many producers and directors as too light to be "authentically" black, she was indignant. Because of that complex construct, race, the stardom she felt ought to have been hers never came. What else did Jane White feel? What might she have thought about the movie version of "The Help"?

Not knowing convinces me of two things: if we don't want whites to always be the ones who gain acclaim for the daring of telling "our" story, we had better get busy. Moreover, in order to best tell some histories, we had better hurry, as well, before it's too late.