He must have thought I was mute. Whenever I saw his sparkling smile and slightly-bowed legs coming down the junior high halls anywhere near my locker, my brain short circuited, and I could not speak. I would look down, away, anywhere his gaze was not. To my 12-year-old eyes, he was pure chiseled jaw, tousled dirty blonde hair perfection. But as flawless as I saw him, I was that intensely uncomfortable in my own pimpled skin. I took Latin, was so skinny I hated the word, was of the odd half-Jewish/half-Catholic lack of persuasion, wore railroad track braces, bit my fingernails so badly they looked as though they'd taken a spin in a blender, and edited everything I was about to say so nothing "weird" unbefitting a normal seventh grader escaped. He was so far out of my league, he was on another planet.

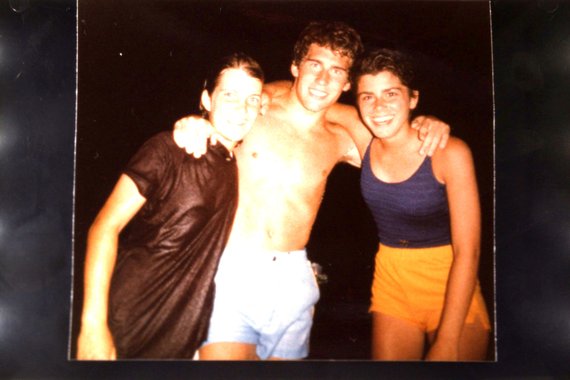

As middle schoolers still do, my friend Tina told him that I liked him toward the end of that school year. Unlike the several others she'd approached on my behalf earlier that year, he said yes. He'd "go with me," which meant we were officially boyfriend and girlfriend. We could hold hands in the hallways and kiss goodbye before getting on our respective buses at the end of the day. (We did this exactly once, and I remember he had to raise to tippy toes to plant a quick, wet peck on my lips.)

He would meet me after class to walk me to classes, but I barely said a word. There was nothing I could possibly think to say to him that'd be good enough or make me seem like the normal, fun-loving seventh grade girl I imagined he'd want to be with. He called me at home as the summer after seventh grade was starting. I was heading out to the roller rink with Tina, my mom was standing next to me waiting to drive us, so I hung up quickly. But he'd called. I roller skated faster and tried more tricks that night than ever before. I was the 13-year-old, white, suburban Donna Summer on roller skates.

I called him back that night while enjoying a bowl of Breyer's chocolate chip and awaiting The Battle of the Network Stars. Erik Estrada was supposed to be on, and I was looking forward to the Speedo-clad swimming competition. "I don't think we should go out anymore," he said tentatively. "Why not?" I squeaked. "We never talk." That was true. I couldn't argue. I could only feel shame at my inability to speak in front of someone I wanted to connect with so badly that the possibility of embarrassing myself paralyzed me with fear.

He went on, dating cheerleading captains, tennis players, underclassmen, upperclassmen -- you name it. I remained mute in his presence. Tina even tried again. Telling him during track practice in tenth grade that I liked him. The next day he came up to my desk in biology class and started talking to me. I'd just blown my nose with a napkin. How could I speak when there may be errant snot dangling unattractively from one of my nostrils? The next day he strode into biology, beaming, while another boy slapped his back, in awe that he'd just been asked out by the school's most popular senior girl. He must have seen my face fall. He shrugged and half-smiled in my direction. Opportunity gone.

I was unable to put a full sentence together in front of this sweet soul of a boy through senior year of high school. He even wrote "call me XXX-XXXX" in my high school yearbook. But I didn't think that actually meant he wanted me to call him. Why would he?

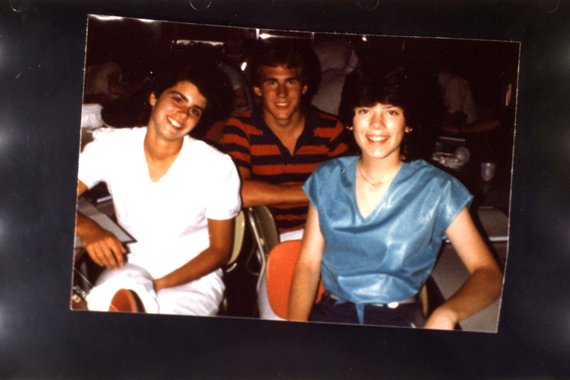

At our 30-year high school reunion, he greeted me with a "hey girl," as I was signing in, but instead of continuing the conversation and finally establishing a connection with someone who'd been the center of my existence for seven years, I easily distracted myself with another classmate I'd connected with recently on Facebook.

He suddenly and unexpectedly died this past week at the age of 48, leaving behind a kind and loving wife of 22 years and two grieving, young sons. He also left a community that adored him as evidenced by the line of people at his viewing and standing room only church service. His was truly a life well-lived, and one that I was never graced to know.

While it may be easier to see when we're younger, our fear of each other can live indefinitely. It is a prison we alone sentence ourselves to. We're so afraid of rejection that we put up walls to keep the hurt out, but the only thing we succeed in doing is keeping life out.

When someone from your childhood dies, it's a slap of reality that those wonder years are further away than we'd like to believe. It's also a reminder that the only way to really live is without fear. As we age, fear becomes our addiction, the only way we know how to be, but it's a trap. There's another way. We just have to learn to work that muscle first, not last.

Take it from this half-breed with pimples and a freakishly large vocabulary: We're all weird, and we're all afraid. The worst thing you can do is let its grasp become you.