I never understood why anyone would fly 24-hours from California to the African bush only to potentially be eaten. After three days at the Madikwe Safari Lodge I get it.

The dichotomy of sheer luscious luxury in the midst of the brutal wild is as good as it gets. And you're safe because the person who comes between you and a she-lion eating you like digestive cracker in a Trafalgar pub on Sunday is your bush guide.

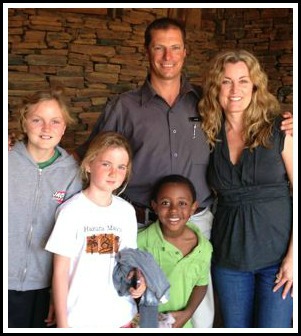

Ours is a gentleman named Andre Nell, who greets us cheerfully each morning at 5:30 a.m. and again around 4 p.m. to take us into the sub-tropical, north-west South African veld that borders Botswana. He is our animal interpreter, our biologist, our zoologist, our soldier, our nurse, our libations expert and our gracious host.

(That's Andre with his arm around me. Yes, I've managed to crop my husband out of the shot, but only because it wasn't a very flattering picture of him. Or this could be our Christmas photo. Hmm.),

(That's Andre with his arm around me. Yes, I've managed to crop my husband out of the shot, but only because it wasn't a very flattering picture of him. Or this could be our Christmas photo. Hmm.),

(Here Andre sets up our sundowner at the golden hour in the bush. I developed a taste for gin and tonic.)

(Here Andre sets up our sundowner at the golden hour in the bush. I developed a taste for gin and tonic.)

Today, when a seven-ton male African elephant bull in full "Musth" (i.e. quite ready to mate -- visibly sweating testosterone) wouldn't move off the road we were forced to follow him in our picayune two-ton jeep at a snail's pace for the better part of a half-hour.

Four times (and yes, I counted) said elephant whipped around, glaring at us wild-eyed and dust-snorting, flapping his ears at us like an enemy army brandishing its flags. My eldest daughter and I shrunk down in our seats in dread and all of us looked to Andre for our cue as to how to behave.

("You talkin' to me? Then who the hell else are you talkin' to? You talkin' to me? Well, I'm the only one here. Who the trunk do you think you're talking to?")

("You talkin' to me? Then who the hell else are you talkin' to? You talkin' to me? Well, I'm the only one here. Who the trunk do you think you're talking to?")

"We challenge him," replied Andre.

"What does that mean?" I asked, thinking one of us might have to run out with a sword shouting "En garde."

But no, apparently challenging a massive Proboscidea requires that you simply stay silent and don't move. Which, to me, seemed a bit like freezing in terror, but Andre has lived in the bush his whole life and after three days as his pupil I trusted he knew exactly what he was talking about. And sure enough, moments later, said elephant harrumphed haughtily and moved off into the tall grass.

(Side story: Andre took his three-year old daughter on one of their frequent rounds in the bush and captured a black mambo with snake tongs to be relocated off safari grounds. The following day his daughter demanded the snake tongs at home and took them outside. Andre thought she'd gone out to gather leaves or dig in the dirt only to discover his daughter standing behind him in the kitchen carrying a Cobra she'd captured with his tongs. His heart dropped to his feet, but he stayed calm. Extricating both tongs and snake from his toddler's grasp. He told her she'd done everything exactly right, but explained he didn't want her helping to relocate snakes until she's a bit older. End side story.)

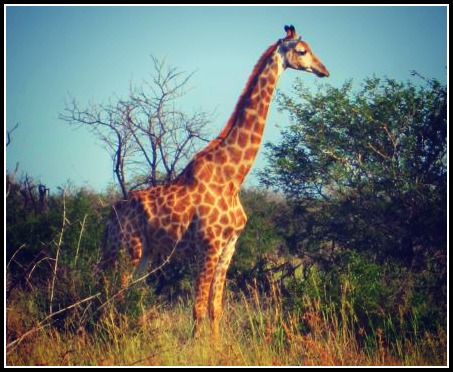

I feel free to ask Andre all of my burning questions, including, perhaps, the stupid ones. ("Do giraffes have joint issues and if so, do you perform perform knee replacement surgery on them?" "Can impala and wildebeests mate?" "Can I pet an African wild dog?" Answer: "Not if you want to live"). Andre's genuinely enthusiastic tutelage regarding this natural ecosystem is to my soul what cool, fresh, life-sustaining water is to a parched throat.

Those of us from the citified realm may not even fully realize how starved we are to reconnect with the natural world until all five of our senses are engaged.

We smell the rich, loamy scent of the red, earth in the veld or the acidic, indescribably ripe scent of a bull elephant in "musth" or the burning elephant dung that smells exactly like the dark, rich pipe tobacco your grandpa smoked when you were a child and it grounds us in our bodies.

A gin and tonic quaffed next to a four-foot high termite mound tastes extra crisp and delicious.

The vibration of the Jeep over the pits and gullies and watering holes of the bush lulls you into the same rhythmic gait the larger mammals adapt.

Hearing the roar of a female lion in search of her pride raises goosebumps.

(The lioness on a roaring break just past my right shoulder.)

(The lioness on a roaring break just past my right shoulder.)

And seeing all of nature's inimitable colors in its phantasmagoria of creatures is humbling. We humans are quite monochromatic -- just pink, brown or black -- by comparison.

We cannot know how we yearn to live among the wild beasts until we are indeed among them. Today our jeep stumbled upon a journey of giraffes -- I counted at least 15 -- and was mesmerized by their tentative, stilt-stick gate. Several minutes after encountering the lioness roaring for her pride, we heard the deafening 120-decible roar of her male counterpart, seeking her in return.

Going on safari also seems to call forth our sixth sense, by which I do not mean seeing dead people, rather, I mean intuition. Which boils down to knowing one's place in the pecking order of the wild.

I asked Andre why the female lion wouldn't leap into our Jeep and eat us one by one. He humored me by explaining -- I'm sure for probably the thousandth time -- that we don't smell like prey. We (as an entity merged with the jeep) smell like rubber and diesel and humans. We also don't appear as individuals when we're in the jeep. It's only when we step on the ground and move away from the Jeep that we individuate. And we also appear aggressive in that circumstance. A wild animal's response to aggression is to return the favor.

I tend to anthropomorphize animals -- which is to say I want to make the human. I didn't just want to pet the African wild dogs, but also the she-lion, the baby elephants, the water buffalo and the rhino, the Kudu, the Heartabeests, the impala, the giraffes, the zebras, the wildebeests, the warthogs, the striped mongoose carrying their young, but was told to do so would be foolhardy at best and destructive for the animals at worst.

"Once you establish intimacy with a wild animal," said Andre, "it is no longer wild, and that is very dangerous for the animal."

It's been humbling to be reminded that we humanoids must share our planet with these exotic creatures and be respectful of their right to exist.

We packed our bags this morning and are heading to Cape Town tonight for the second leg of our journey. As I hugged all of the people at Madikwe Lodge who made our visit so memorable, Rebecca, Moses, Comfort, Jeremy, Billy and Andre, my eyes welled with tears. It might just simply be a case of 47-year old hormones. Or it may be, as Andre said, "that when you leave the bush, you leave a small part of your heart with it."

To see more of my photos and read all about my family's African safari you can start here ... http://thewomanformerlyknownasbeautiful.com/2013/02/safari-bound-day-two-and-three.html