I thought my sister wanted me to do something. To say something.

To write something.

Lisa's text message asked whether I had commented at People.com on the story of Brittany Maynard, the 29-year-old glioblastoma patient who moved to Oregon in order to legally choose assisted suicide. In making this choice publicly, her story has generated a fevered response of those condemning her decision or validating her right to choose the moment when her life, and suffering, will end.

No, I hadn't commented. I'd been avoiding it.

Why? Because of my father.

As I've written about on The Huffington Post and elsewhere, my father is an almost nine-year survivor of the same disease. He was initially given months to live, and through what I believe to be a combination of luck, excellent medical treatment from the team at the Preston Robert Tisch Brain Tumor Center at Duke University Medical Center, and the willpower of a man who barrels furiously through life with an almost pathological desire to control his circumstances, my father still lives over these many impossible years.

Even so, his life is one of considerably depleted circumstances. He is aphasic, stooped, and trapped all too often in a series of tape-loops and repetitive behaviors that are together like the familiar arrangements of a fragile child's playroom: The pills must be placed in exactly the same spot on the nightstand. The slippers must be aligned in perfect parallels just this much under the bed frame. His glasses must be cleaned and cleaned again, buffed by the hands of my mother to the clarity of the Hubble telescope.

He is degraded. Confused. Distraught.

And, at times, he is joyous. Filled with a powerful love for everyone in his life -- his wife, his children and their spouses, his grandchildren -- he is overcome with emotion. He will take a slice of cake baked by my wife, and speak its virtues with the fragmented intensity of someone for whom every bite is sacred. He'll drink coffee, particularly if "you're having some," and he'll take it boiling hot, steaming, so that he knows by the burn in his throat that he is alive, and that he is with you now, and that he loves you more than he could ever say when he used to be someone else.

Yes, Phil Schneiderman is alive.

And so my sister wasn't asking me to post a comment, but making sure I hadn't posted already. Sure enough, in the thousands of responses to Maynard's story, amid the arguments on either side, was a comment from a fake "me." Yep. An Internet commenter impersonated me, lifting text from my a previous HuffPost blog I wrote about my father.

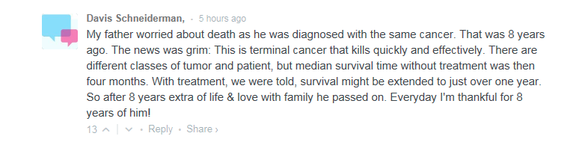

And, to top it off, this person killed my father: "So after 8 years extra of life & love with family he passed on. Everyday I'm thankful for 8 years of him!"

In my work as a creative writer, most recently in a series of conceptual novels, I've played perhaps in the same sandbox. My most recent book [SIC] is completely appropriated from many well-known literary and cultural sources (Shakespeare, YouTube) as a way to discuss ideas of authorship, genius, and creativity. At other times, I've put mustaches on Shakespeare sonnets, alphabetized the first paragraph of Proust's Swann's Way, and recently wrapped a long conversation with author David Shields for The Writer's Chronicle on the place of collage in contemporary culture and the literary tradition.

I've taught a "remix and mash-up" writing workshop, and facilitated assignments where students play with Wikipedia and deploy imaginative Twitter accounts. In short, I believe in the sacred ownership of words about as much as Einstein believed in space dragons.

But I've never killed my father.

And yet I am upset by this plagiarism and forgery, meant to further an Internet argument in the sloppiest of ways. Why?

Because my father is alive. And because I can never explain this to him.

Once, I could have, when he was someone else, before glioblastoma.

What does it mean to survive brain cancer? In some ways, this is one question Maynard's decision and my father's life continue to ask.

If the way a persons dies says something not about how a person lived, but about how we confront death, what does Maynard's decision to die tells us about cancer, about choice, about what we would do if faced with the same circumstances?

I wouldn't begin to tell Brittany Maynard whether she should continue to fight and to suffer, or whether the act of choosing when to die is the right one. I wouldn't tell anyone with brain cancer what "life" will become for them on that almost impossible chance of survival.

No, I don't know anything about that.

I do know, dear Internet troll on People.com, that Phil Schneiderman still lives. I know that I am thankful for this fact and terrified by it at the same time.

I know that the meaning my father's slow death -- and yes, his continuing if uncomfortable life -- may well be no meaning at all.

So, please, Internet troll, don't bury a man who (if he gets his way) will still be here 10 years from now.

And don't -- how can you? -- presume to tell anyone when a life may end.