As Malaysian activist Adam Adli was sentenced to a year in prison for making anti-government remarks, one thing remains certain: the 25-year-old's conviction has only solidified a personal resolution of his own.

Under the country's Sedition Act, a 1948 law that criminalizes any speech that "bring[s] into hatred or contempt" or "excite[s] disaffection" against the government, Adli was convicted at a Kuala Lumpur court in September for his comments at a forum on electoral reform last year, although it is not clear what he said.

The government has prosecuted 13 others this past year, but Adli's 12-month sentence makes his penalty likely the highest of them all, according to Human Rights Watch. After handing down the verdict, the court allowed him a stay and Adli was freed on bail, pending an appeal.

Adli's conviction isn't surprising to those who follow his story. Since his first protest three years ago, the law student has emerged as an unofficial poster boy for the movement opposing the United Malay National Organization (UMNO), inspiring candlelight vigils for his detention, getting arrested more times than he can count and inadvertently delaying his education. On Twitter and Facebook combined, his followers reached a staggering 44,000, all of whom received his updates throughout the sentencing. "Guilty. Akan update lagi," he wrote in one Facebook status. "Will update again."

He even posted a selfie to Instagram, presumably taken in the courtroom. "Keep calm and be seditious! #MansuhAktaHasutan" read the caption, in reference to a grassroots campaign to abolish the Sedition Act, which critics say has given rise to a virulently arbitrary crackdown on the freedom of expression.

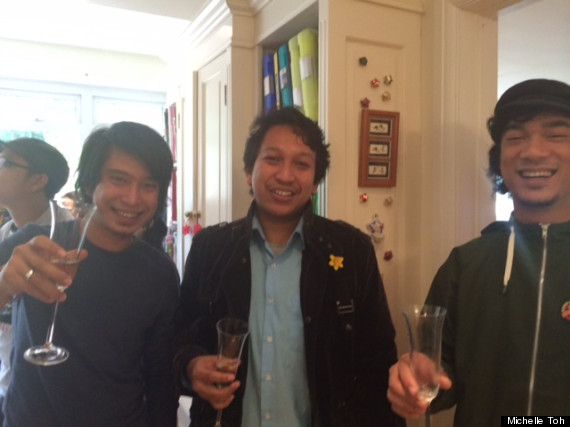

I was introduced to Adli this past April in London by a family friend, who told me that a troupe of actors called Teater Bukan Teater ("theater is not theater") was on its way to the city. There to raise awareness to the censorship that remains very much alive and well in Malaysia, the group staged performances at a number of universities across the U.K. of a dark-titled play, "Bilik Sulit," or "The Confidential Room."

Standing before several dozens of college students in a darkened room, the spotlighted Malaysian actors laid bare somber imagery of police brutality under the Internal Security Act, a law under which they had, in some form or another, experienced personal interrogation before its repeal and replacement by the Security Offenses Special Measures Act in 2012. At forums afterward, the actors met with students to take questions and share their personal stories.

One was Sidiqin Omar, a 32-year-old subeditor of alternative newspaper Keadilan Daily, who said there was no freedom in the press. "The culture of the Malaysian government is to hide," he declared. Despite the publication being banned by the state, it continues to have a circulation of roughly 160,000, he said, based on distributors "who are willing to take the risk."

What bound Teater Bukan Teater together -- a coalition of individuals vastly different in age and experience -- was a desire to impart to the public a common theme of suppression.

As the team's manager, Adli was at the helm of it all. We met several times over the course of his stay, gathered with the group around the pushed-together tables of a Costa Coffee; sitting in a three hour-long interview in my living room; watching a comedy show by another famed fellow Malaysian activist, Hishamuddin Rais; eating nasi lemak and curry at a friend's family home. London's Malaysian community is relatively tight, and everywhere we went, everyone seemed to know each other. We soon became friends.

As we walked past painters in my apartment building one Friday morning, they stared at us and smirked. Given Adli's presence in the national political forum and fervent grassroots following, it seemed strange to me that they didn't know him.

Adli, a wiry guy with longer-than-usual hair he often sweeps out of his face, came across surprisingly soft-spoken and exceedingly polite for a rabble-rousing activist. The times we met, he spoke in a calm, low voice that would gradually ascend as he began talking about policies he saw as unfair or hypocritical, such as that of a nationally-known college in Selangor, the University of Technology Mara. UITM claims to be "a Malay-only" institution, he said, insisting that admission is not open to Malaysian citizens of other racial backgrounds. Yet the university takes international students, he pointed out.

The elder son of a train driver father and a factory worker mother, Adli was raised in the suburb of Bangsar in Kuala Lumpur -- "not the upper side of Bangsar, where the middle class and upper class live," he said pointedly. "I grew up in the actual working class area, where there were only a few flats that were occupied by the railway workers."

It grew evident that Adli's childhood had played a vast role in his perception of Malaysia's oft-discussed socioeconomic divide. At the age of 45, Adli's father was forced into early retirement for health reasons, and their family moved back to their home state of Penang, where he worked part-time jobs for two years while completing high school. "Nothing like Costa Coffee," he laughed. "No such thing as that. More like the hawker stalls."

Despite his modest upbringing, he never doubted he would go to university, he said. "Not to say I'm good," he said quickly. "Just that in the whole 12 years of school, I always would find myself among the top students."

In 2009, Adli began attending Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris (UPSI) in the state of Perak, a former public teaching college that was slightly cheaper compared to other universities. Many of his peers received tuition money from the UMNO Party's racially targeted scholarship program, he said, yet another scheme in a line of many aimed at making Malays more competitive.

"The words of the government have always been: 'The Malays need to compete with the Chinese, in terms of economy,'" he said. "Didn't change anything -- the Malays are still the poorest group."

It was this perceived partisanship, alongside extreme corruption, which Adli observed "even from little things, even teachers," that prompted him to embark on too many demonstrations to count. "We have worked hard for reunification, for reintegration, for people from different backgrounds," he said, others nodding beside him.

He remembers his first campaign, a 2011 rally against the privatization of water. After that, water was provided for free, he said, giving him and his peers a great sense of triumph.

Rarely, however, do results come so easily. Adli said he and his fellow protesters are often pelted with teargas and water cannons, to the point of predictability. "You always have to expect that the government is going to come out with full forces," he shrugged.

The 20-something wasn't always this nonchalant. Turning to my laptop, Adli pulled up a video of UMNO supporters uploaded onto YouTube years ago after a demonstration. In it, a group of thuggish men sitting at a town hall meeting furiously shout in Malay, imploring the public, it appears, to do something. What were they saying? I asked. "Find me," he said.

The video prompted a chilling phone call from a friend, who had seen the video and said he might be in danger. On his friend's urging, Adli drove to another friend's house to hide for a few days.

The student's first arrest came in 2012, a year after his initiation to activism. Protesting for greater academic freedom on campus led to his and his fellow demonstrators' suspension from the university, he said, on the charges of "damaging the reputation of the university." After nine days, his friends were allowed to return. Meanwhile, Adli, who had led the campaign, was placed on indefinite suspension.

"They called it the 'Uprising of the Students' during my time," said Adli matter-of-factly, adding that he hoped to return to his studies soon.

His time, I replied, still seemed to be very much alive and provoking debate. What's your greatest fear? I asked.

He paused. Making "a fool" out of my supporters, he said. "I don't want to be a snake."