Approaching Nanda Devi, I arrive at the Kuari Pass, where the Curzon Trail crosses over into the Dhauli Ganga valley. At an altitude of 11,000 feet, the pass is relatively low by Himalayan standards, but opens onto a spectacular panorama of snow peaks, all of which rise over twice that height. The challenge of Kuari Pass is to reach there as early in the day as possible. Clouds often gather by mid-morning and soon there is nothing to be seen.

My companion, Mukesh, and I break camp before daybreak and reach the pass at 9:00 am. It is the first week of November and all of the streams we cross are rimmed with ice. Yesterday we met a party of trekkers but today there is nobody else along this route, except for a red fox that crosses below us, the white tip of his tail like frost on the grass.

Kuari Pass faces the inner core of the central Himalayas, which form an arc of 180 degrees, from Chaukhamba, the four pillared mountain, across to Nilkanth, Mana and Kamet. Directly in front of us are Ghori and Hathi Parbat, the horse and elephant peaks, caparisoned with fresh saddles of snow. And, farther east, Dhunagiri's white pyramid cleaves the sky. Seated next to a cairn that marks the pass, I feel as close to the mountains as I can be, without actually setting foot on their slopes. The only disappointment is that Nanda Devi is hidden behind the Pangarchula ridge. We will have to wait until we descend 1,500 feet below the pass, before the mountain reveals itself.

The Curzon Trail used to be the traditional approach to Nanda Devi, before motor roads cut their way through the valleys of Kumaon and Garhwal. In 1900 it was prepared for the viceroy of India, who was intent on getting a first-hand look at the highest reaches of the British Empire. This was the period of the "Great Game" when England and Russia were competing for influence and power on the roof of the world. In the end, however, Lord Curzon never made his intended journey to the Himalayas, though his trail has served many pilgrims, shepherds and mountaineers.

Our path appears and disappears as we descend across grass-covered slopes below the pass, circling the ruins of herdsmen's huts and a stone corral. There seems to be no sign of life and the only movement is dry grass whisked by the wind.

Just before we drop back down below the tree line, a bearded vulture takes flight with wings that eclipse the valley for a second, a feathered shadow detaching itself from the rocks and soaring out to meet the clouds. I feel a sudden sense of loneliness and exposure above the trees and am glad to enter the forest, though we have been warned of bears. At Chitrakantha, which means picturesque point, we finally catch sight of Nanda Devi, emerging above the ring of peaks that guard her sanctuary. The steepled summit is like a vast cathedral that has taken millions of years to carve, buttressed by eroded ridges and corniced with ice. By this time, clouds obscure all of the other mountains and only Nanda Devi is visible. In the sky above her floats a gibbous moon, so faint that I mistake it for a scrap of cirrus orbiting her sacred summit.

Nanda Devi is known as the "bliss-giving goddess," though the Sanskrit word "ananda," at the root of her name, is better understood as "contentment." Being an atheist, I seek the mountain more than the goddess, though the two are inseparable. Despite my disbelief, I have always appreciated the spiritual resonance of the Himalayas. Topography and myth converge in a mysterious, multi-layered landscape of narratives - colonial, religious and ecological. Nature takes on many different forms, as rock and ice, lichen and moss, bird and beast, air and sunlight, just as the gods assume their various permutations.

As the last rays of sunlight set the mountain aglow, I trace Nanda Devi's familiar profile, which I have admired so often at a distance. Seen here from the slopes below Kuari Pass, she stands much closer, a giant shard of rock and ice, pushing up from the fault-lines of the Himalayas, where the subcontinent of India collides with the rest of Asia. Nanda Devi's eastern summit is hidden from this angle but the distinctive features of the main peak are clearly visible, the broad shoulder to the west, with epaulets of snow. The second highest mountain in India, at 25,643 feet above sea level, she rises abruptly in a steep, unrelenting rock face that only eases near the summit, before plunging again several thousand feet to the east. First climbed in 1936 by Bill Tilman and Noel Odell, Nanda Devi appears inaccessible, inviolate. I study the fluted snowfields and couloirs of ice, scoured by avalanches. Horizontal bands of rock curve downward, as if bearing the weight of the sky.

Looking up at Nanda Devi, I can imagine a mountaineer trying to map out a new route of ascent. Alpinists speak of perfect lines the way physicists speak of elegant equations, those paths they follow to conclusion. A climber's hands can feel the rocks long before he touches the mountain. Just as I share the mountaineer's vision, I find myself observing Nanda Devi through a pilgrim's eyes. The clouds and snow spume that drift about her summit are said to be the smoke from sacred fires of mystics who sit atop the mountain performing rites of worship for the goddess. (One Englishman referred to it as "Nanda's kitchen".) This mountain stands out from the rest, not only because of her altitude but also through a natural symmetry that suggests perfection.

In one of the more playful Hindu myths, Lord Shiva and his bride, the mountain goddess, are cavorting in the Himalayas. Teasing her omnipotent lover, the goddess sneaks up behind him and innocently covers his eyes with her hands. Suddenly, the world disappears into a void of darkness. As creator and destroyer, Shiva's vision brings the universe into being. When his all-seeing eyes are closed, nothing exists. The light is extinguished and we plunge into darkness. Alarmed, the goddess removes her hands and restores the world as we know it.

The dramatic contrasts of darkness and light that we observe high up in the Himalayas, particularly at dawn or dusk, elicit simultaneous feelings of fear and elation. Nineteenth century philosophers described these extreme encounters with nature as the paradox of the sublime. Essentially, the sublime is a kind of emotional vertigo that leaves us both unsettled and inspired. This experience places us at the edge of a metaphorical precipice that is even more disturbing and uplifting than the cliffs that drop away beneath our boots. It is, perhaps, the primal reflex that provokes in some, their search for a divine creator and destroyer.

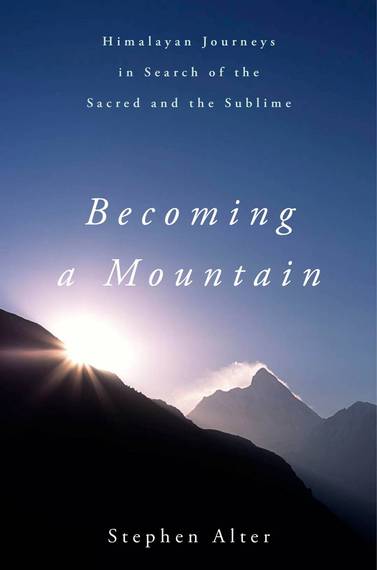

Stephen Alter's Becoming a Mountain: Himalayan Journeys in Search of the Sacred and the Sublime is published by Arcade/Skyhorse (2015)

For more information go to www.becomingamountain.com