If you head south on route 183 in central South Dakota, you'll see sprawling farmland all around you. Bald eagles, some as tall as children, will stand guard at the side of the road and swoop low over your car.

And if you look to the left at the right moment, you'll see a circle of five giant, white teepees standing in the center of one of the fields. You may wonder what they're doing there, and if you're inclined to take a detour off the highway, the people living in the teepees will welcome you with food and stories of why they're there.

Since March, Keith Fielder has been one of the people living in those teepees. The teepees make up a Spirit Camp, built in opposition to TransCanada Corporation's proposed Keystone XL pipeline.

"This is the only spot in the U.S. where the pipeline would get this close to Indian land," Fielder says, nodding toward two ceremonial sweat lodges set up 50 ft. south of the teepees. Here, the proposed pipeline would have to bend around Native land. And here, the people pray for protection for Mother Earth.

A former engineer, Fielder now works as an archaeological monitor with the Rosebud Sioux Tribe in central South Dakota. Rosebud Indian Reservation sits next to Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, home to the Badlands and the Black Hills. Fielder travels throughout the U.S. and Canada to analyze geographic sites like those for historical preservation.

He says that the pipeline threatens culturally sacred lands. And last spring, with the majority of Congress pushing to make this new portion of the pipeline a reality, seven Native American tribes came together to form the Spirit Camp. Non-native-owned farms and ranches surround the camp, which sits on an isolated plot belonging to the Rosebud Sioux tribe.

But for Fielder, the pipeline doesn't only threaten historical lands. "It's all about the water," he says, as he drives his pickup truck down a bumpy dirt road to the middle of a snow-covered cornfield. At the end of the road, the circle of teepees stands surrounded by stacks of hay bales. "We spend billions flying spacecraft to other planets to see if they have water, and here we're about to destroy ours."

Thousands of people in Montana right now understand the severity of that threat. They can't drink or cook with their tap water due to 50,000 gallons of spilled oil. The oil flooded Montana's Yellowstone River in mid-January, causing many people to report smelling diesel fumes in their homes.

That breached pipeline measures 12 inches across. The proposed Keystone XL pipeline would be 36 inches.

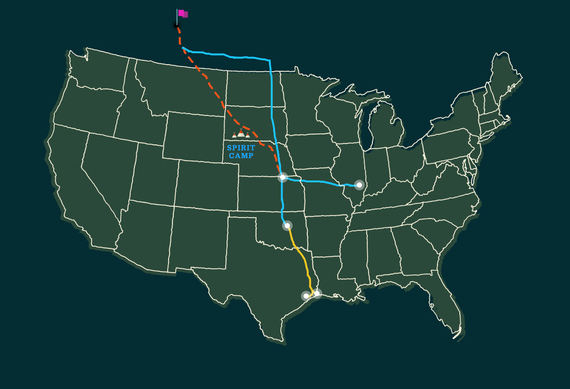

And in TransCanada's plans, the new portion of pipeline stretches south from Canada in a diagonal line across Montana, South Dakota, Nebraska. From there, the oil would travel to the Gulf Coast and leave the U.S. for markets around the world.

Building the Camp

At the Rosebud Spirit Camp, school children, politicians, farmers, journalists, cowboys from Nebraska and people from around the world have all visited. They leave behind prayers, well wishes and flags of their own nations to show their support.

"This isn't just Indians, it's the whole planet. We're all connected. What we're made of here goes clear to the end of this universe," Fielder says.

Through pounding rains, whiteout blizzards and extreme heat, thousands of people have stayed at the Spirit Camp in the past 10 months.

"We always talk, but this time we wanted to really get boots on the ground," Fielder says.

Since winter arrived, however, the camp's population has dropped. Most people headed home when school started in September. More recently, with temperatures in the area dipping as low as 20 degrees below zero, only a devoted skeleton crew keeps the camp running.

They don't plan on leaving anytime soon.

"A long time ago in our history, our ancestors said a black snake would come through and that we'd have to put up resistance," Fielder says of the proposed pipeline. "So here we are."

Beside him stands Leota Iron Cloud, a key contributor to the camp since its inception. In addition to helping run the camp, she also offers perspective.

"Here, we're all about prayers and spirituality," Iron Cloud says. "Our ancestors went through worse conditions than this. So thinking about them and the future generations to come keeps us going, keeps us strong."

Last September, Iron Cloud left the Spirit Camp to walk in the People's Climate March in New York. She joined 300,000 others from across the country and around the world.

"It opened my eyes to the bigger world. So many people out there want to save Mother Earth," Iron Cloud says.

How the Pipeline Works

Parts of TransCanada's Keystone XL pipeline already exist. The current track runs from Alberta, Canada to refineries in Illinois and Texas. Builders completed those portions in 2010 and 2014 respectively.

(Map by designer Dan Leu)

The Midwest portion of the pipeline is capable of receiving nearly 600,000 barrels of oil per day, while the Texas refineries can receive 700,000 barrels per day.

But plans for a pipeline across the U.S.'s upper plains does not sit well with many -- especially those who live in its proposed route. That route cuts across Nebraska's environmentally protected Sand Hills region and the Ogallala Aquifer.

One of the largest aquifers in the world, the Ogallala Aquifer covers 174,000 miles in portions of eight states: South Dakota, Nebraska, Wyoming, Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, New Mexico and Texas.

At times, its water level is only 1 ft. below ground. A potential pipeline break or leak could severely pollute it.

But that's not the only risk, Fielder says. Waking up everyday to check Keystone XL news before doing anything else, he struggles to fit all of the issues the pipeline raises into one conversation.

He worries about women who have gone missing near the "man camps" (groups of men working on the pipeline) and the "sky-rocketing cancer rates" near oil harvests in Canada.

Another question on his mind: "All of these carcinogens moving through the pipeline, where are they going to go? Are they going to destroy another town in the U.S.?"

Looking Forward

While the potential problems cause stress for some, Fielder says he feels more sadness than anything else.

"It's a sadness that others are willing to destroy the earth," he says, describing a place he read about in Canada, where workers dug so deep into the ground that oil now seeps out into the land.

"I think of scratching myself so deep that I bleed, and they're doing that to Mother Earth. I cried when I read that," he says.

Unfortunately for the Montana residents experiencing the most recent oil spill, such disasters are nothing new. An even bigger oil spill compromised the area in 2011, when 63,000 gallons of Exxon Mobil oil flooded into the Yellowstone River near Billings. The fast-flowing river made the damage hard to contain, and resulted in miles of oil-soaked shoreline, as well as oil-smeared crops and animals. The cleanup totaled $135 million.

Still, Fielder holds out hope. If Congress decides to push forward with the pipeline extension, he says he believes Pres. Obama -- the only U.S. President ever adopted by a Native American tribe (the Crow) -- will veto it.

If Fielder could say one thing to the president, he says, "I'd tell him, 'It's about the water, Mr. President. It's about your kids' kids and their water.'"

He doesn't end there. "And I'd tell Congress, 'You're not really representing the people when you destroy their land.'"

To stay updated on the Spirit Camp, visit the camp's Facebook page. The page, "Oyate Wahacanka Woecun" (Shielding the People) has more than 7,000 followers. Leota Iron Cloud posts updates regularly with photos of the camp and its visitors.