Snow covered the ground during my first trip to Pine Ridge in April. Six weeks later, though, the temperature had climbed into the 80s, and tiny brown wood ticks added polka dot textures to everything -- tree stumps, the outside of tents, the floor of the sweat lodge.

My friend Allison, who had once again made the 14-hour drive with me, went into panic mode over them. I didn't understand exactly why. Unlike deer ticks, wood ticks don't carry Lyme disease. They don't burrow into the skin. They do suck the blood of their hosts, but they're fairly easy to remove. And they loved Allison. This would be her battle.

During her quarter-hourly "tick checks," Allison found them in her hair, crawling up her ankles, and a particularly dedicated one gripped to her earlobe like an earring. Giggling too much to remove it myself, I had to call for backup; Allison stood frozen in place, hyperventilating.

I was finding half a dozen ticks a day as well, but Allison's collection more than doubled that. On our third day in Kyle, she pulled me aside, pale and frantic. In tears, she told me she hadn't been sleeping. "They are everywhere. They won't leave me alone."

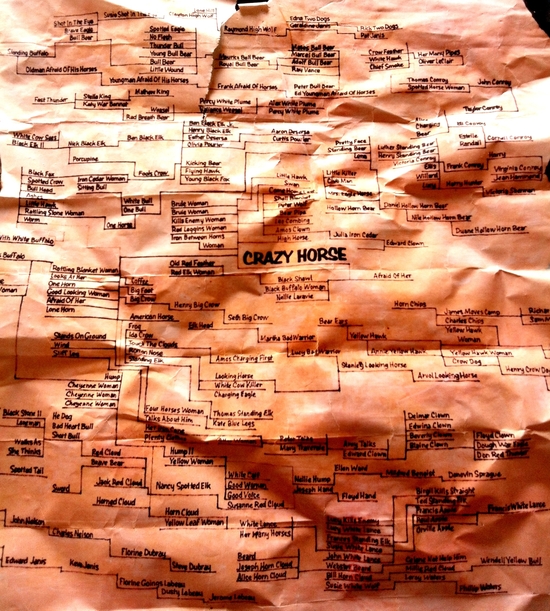

Later that evening, Allison went with me to Delores' house. The family tree, with Crazy Horse at its center, came out during that interview. Delores' son, Ray Takes War Bonnet, Jr., brought it, unfolding the oversized piece of paper and setting it in the middle of the table for us to look over.

Names started jumping out at me immediately: White Cow Killer, Walks As She Thinks, Spotted Elk, Good Voice, Charging Eagle, Frog.

"Frog? How did he get that name?" I asked Delores. She shrugged, uncertain.

A few days later, I learned that "Frog" could be a purposely humble name the person took on later in life. As Joseph Marshall III wrote in The Journey of Crazy Horse: A Lakota History, Crazy Horse was given his father's name -- strong and intimidating -- after he proved himself in battle. (Prior to that, he was called "Gigi" or Light-Haired One.) Now that his son had become Crazy Horse, the elder took the name of the most humble creature he could think of: "Worm."

These symbolic names reflect the spirit of the person. Tatanka, or buffalo, for example, represents protection and sustainability -- food, clothing, shelter, strength. Spiritually, Lakota also believe their names are how the spirits recognize each individual.

But in 1931, the United States government challenged that belief, telling the natives that each child had to take on a last name so that they could be identified by federal standards. Simultaneously, the U.S. government banned the Lakota language, forcing natives to learn English and using the Catholic Church to help spur the change. "Black Robe People," the natives called the priests.

The plan worked in large part because the natives had such profound respect for the Black Robe People -- men who prayed and wore giant crosses over their hearts. Their symbols and actions translated, even when their words didn't. The cross was a common symbol in Lakota spirituality; the heart was where the turtle in the Lakota creation story hid faith.

As Delores and I chatted, her granddaughter came in from outside, scratching at her scalp. "Got another one," Delores said, checking the girl's hair and then sending her back out to play. "Wood tick."

I glanced at Allison who was watching the scene unfold, her mouth slightly agape. She looked back at me, and took a deep breath. "They're here, too," her expression conveyed.

Today, some 80 years after the Black Robe People first came to the reservation, there are about 20 churches on Pine Ridge. One native, who I'll call Buffalo Man*, said he accepts their presence, even though he practices traditional Lakota spirituality. "I don't belittle them because those churches are real for some people. If it helps them, that's good. Pray to who you believe in."

Even though the government tried to take the Lakota names away, they didn't completely succeed. People on the reservation today do carry last names, but names that belong to their ancestors: White Plume, Yellow Thunder, Takes War Bonnet. Additionally, some Lakota parents continue to give their children individual native names.

And some outsiders visit the reservation hoping to earn their own spirit names. "They want to be part of something," Buffalo Man said, adding that people need to find a name in their own culture. Leave the Lakota spirit names, so Lakota spirits can recognize their people.

"People who know their language, know their culture. Say your name, pronounce it, feel it in your own language," Buffalo Man said. "If we can, we'll translate it into Lakota, but it's just a translation."

Allison found her spirit name during that trip. And it was Wood Tick Woman, Ta Skakspa Wiyan, who made the drive back to Chicago with me, checking herself for stowaways every 15 minutes.

*Buffalo Man lives on Pine Ridge Reservation. He is a wonderful, knowledgeable resource who wishes to remain anonymous.