On the early evening of March 15, 2011, in the bedroom of a two-story red brick townhouse in Virginia Beach, Va., Navy Petty Officer Joshua Lipstein put a .45-caliber Glock 21 pistol to his right temple and pulled the trigger. He was 23 years old.

The Navy, after an investigation, ruled that Joshua died "in the line of duty and not due to his own misconduct."

The real story is more complicated. More confusing. More heartbreaking.

His story is unique, but it also reflects the struggles of the 301 active-duty military men and women who died by suicide that year, part of a growing toll of invisible casualties.

It is difficult to reconcile Joshua's last desperate act with the outward blessings of his life. He was young, smart, capable and well-liked. He was recently married and doted on his infant daughter. He was close to and loved by his dad, Don Lipstein, his sister, Emily, and brother, Andrew.

And yet, like many afflicted by thoughts of suicide, he was fighting an undertow so powerful that it was largely invisible to those who loved him, until it was too late. At times, they felt they had somehow failed him.

"What did I do wrong as a parent?" Don still wonders. "There may have been something I could have done to affect the outcome. But I did the best I could."

It was Joshua's wife, Leslie, late that afternoon, who alerted Don that Joshua was talking about suicide. "I don't know what to do," she said in a call from their home in Texas. She didn't know where Joshua was, and she was frightened. "He doesn't sound good at all," she said.

"Call everyone you know and get them over there," he ordered.

Rattled, Don dialed Joshua's cell phone. He waited, silently begging Joshua to answer. He was scared about what to say, what not to say. Seconds passed. Finally, Joshua picked up the phone.

In that final connection, all the love, all of life's hopes and failures and regrets, the anger and despair, the secrecy and deception, all telescoped into those few precious minutes. And left, in the desperation of that moment, unspoken.

"I said, 'Josh, what's going on?'" Don said. "I could hear him crying. He always put on a strong face for me. But he was crying and he said, 'Dad, I'm so sorry, I love you. I'm so sorry!'"

"I knew I had to keep him on the phone. I said, 'Joshua, where are you?'"

"I can't tell you."

"I said, 'Do you have a gun with you?'"

"Yes, I do."

"Could you just unload it, please?"

"I can't do that."

"I was clutching at straws trying to keep him on the phone. 'Please tell me where you are, please give me an address.'" Silence. Then in a choked voice, Joshua said the address.

"Then suddenly his voice got real strong. He said, 'Dad, I love you. I have to go,' and he hung up."

Quickly, Don dialed 911 and relayed the address, sending cops speeding toward the townhouse. Don thought, maybe there's hope.

Don, 54, is a strong person. Warm, friendly, outgoing. In the 30 months or so since Joshua died, he has endured unimaginable suffering. Battered by shame, guilt, an agony of regret. Anger. And the unanswerable questions: How could this have happened? How did we get to this point? What was my own part in this? Where did I fail? Frantically searching for the understanding that will never come.

Slowly, over the months, he has built a small space of acceptance, of peace. With the help and support of many others, he works at enlarging that space. He survives. To pass him on the street, to exchange neighborly pleasantries, you would not glimpse his torment.

But in coming to this part of the story, the moment his son hung up the phone, Don falters and goes silent, eyes downcast. A long pause. Then he looks up at me, one father to another, and his eyes are luminous with pain.

"I knew," he said.

It was three hours, though, before it was official. By that time the Virginia Beach police had arrived and secured the site. Joshua's best friend, Elliott Miranda, had heard from the family that Joshua was in a bad place. He had called Joshua's roommate, told him to go home and check on Joshua. Elliott had been frantically calling, but Joshua wouldn't pick up. Finally, Elliott heard back from the roommate, and called Don and broke the news: Joshua was dead.

Unraveling the skein of events that led to this end, it's hard to avoid seeing what experts say is a major factor in suicide: the powerful influence of drugs and addiction that can deepen depression and hopelessness. Easy, in retrospect, to spot the missed opportunities for intervention.

THE PERIL OF PAINKILLERS

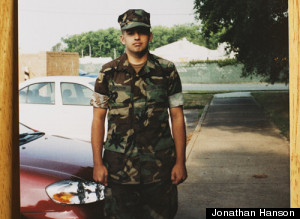

Joshua had been voted class "party animal" when he graduated from Mount Pleasant High School in Wilmington, Del., in 2005. Then he enlisted. By the end of that year, Navy boot camp had scoured away most of his boyish clowning, but not his enthusiasm for life. He loved his two combat tours in Iraq with a Navy river patrol unit, Riverine Squadron 1, hunting insurgents and weapons caches along the Euphrates River in bloody Anbar Province.

He made friends easily and was a good friend. His buddies used words like "energetic" and "optimistic" to describe him. "An infectious smile, the men all adored him, a great brother in arms. Josh is a hero," said Navy Cmdr. Gary Leigh, Joshua's squadron commander in Iraq, who was "crushed" by Joshua's death.

Joshua won promotions. He planned to re-enlist. A distinguished naval career beckoned.

Then, a setback. On his return from Iraq in 2009, a routine physical turned up hearing loss, evidence of a brain tumor. Surgery, in December of that year, was successful; the tumor was benign. But his hearing loss and the surgery abruptly ended his dream of a Navy career. Instead, the Navy began the lengthy process of terminating his service on medical grounds.

In recovery, Joshua was prescribed a cocktail of drugs for pain, anxiety, nausea and other side-effects of surgery: diazepam (Valium), the anticoagulant heparin, the painkiller Percocet, and five other drugs.

The Percocet, in particular, was a peril.

The Huffington Post has pieced together the trajectory of the next 15 months from Joshua's medical records and Navy investigation reports shared by his father, from Naval Criminal Investigative Service documents obtained under the Freedom of Information Act, from interviews with Joshua's family and friends, and from statements issued by the Navy in response to questions.

Joshua's mother, Melinda, had struggled with narcotics for years, creating considerable turbulence at home when the kids were young, Don said. Joshua was extremely close to his mother; there were periods when he managed the family household in Wilmington, Del., for her. By the time Joshua graduated from high school and went off to Navy boot camp in Great Lakes, Ill., his mother had moved back in with her parents in nearby Ocean City, N.J. But she and Joshua stayed in close touch.

That fall, she was diagnosed with colon cancer, and eventually she was taking fentanyl and Roxicet for pain. It was an easy step, when Joshua's own pain prescriptions ran out two months after his surgery, for him to get the opiate pills from her.

According to a Navy investigation, when Joshua's prescription for Percocet expired, "he fed his addiction by asking his mother to send him Roxicet." Roxicet, the report noted, is an oxycodone-based painkiller that "can be habit forming."

Joshua's drug habit surged. From the time of his operation in December 2009 until the end of May 2010, he never went longer than two days without opiate pain pills. Withdrawal symptoms -- muscle soreness, diarrhea and anxiety -- would kick in within four hours without a dose, the Navy later determined.

Early that winter, on Jan. 30, 2010, Joshua showed up at the Naval Medical Center in Portsmouth, Va., complaining of nausea and vomiting, muscle pain, cramps and anxiety. He was given a dose of Zofran, an anti-nausea medication, and sent home. On his patient care report, his smoking is indicated (half a pack per day), but the section on alcohol and drug use is crossed out.

Joshua's roommate at the time in Virginia Beach, near the sprawling naval facilities in Norfolk, was Elliott Miranda. He and Joshua were battle buddies from Iraq. They were beyond best friends, bound together by shared combat. Elliott saw pretty quickly that something was wrong.

"Once he had the surgery I noticed that he was doing a lot of pain medicine, and I never said anything because I figured he knew what he was doing," Elliott told me. "But then things started getting worse. He was more standoffish, not his old energetic self. When I tried talking to him he'd say that nothing was going on, he didn't have a problem. But I noticed he was making more frequent trips back home, I knew he had people who could get him the painkillers."

All that spring, Joshua's drug dependence was deepening even as he remained on active-duty in a military service with a "zero tolerance" official drug policy. Joshua's wife, Leslie, waiting at home in Henderson, Texas, for his release from the Navy, called Don several times, alarmed at Joshua's gradual decline. Each time, Don would call Joshua. Each time, Joshua denied he was doing drugs.

It was a mystery to everyone that Joshua managed for five months to indulge his addiction and stay on active duty. "I don't understand why they weren't drug testing him more frequently," Elliott said of the Navy.

Officially, the Navy requires each of its commands to conduct urinalysis tests of 15 percent of its personnel each month. The Navy declined to discuss Joshua's case. But in response to questions from The Huffington Post, the Navy released a statement saying in part that "service members cannot legally be singled out for drug testing" outside of "command-wide inspections, probable cause tests, search and seizure, and examinations conducted as part of a mishap or safety inspection."

In late May 2010, Joshua's mother, Melinda, was rushed delirious to a hospital in New Jersey after an overdose of fentanyl and Roxicet, according to Navy records. Joshua was frantic with worry for her -- and anxious that he would lose access to her painkillers. He later told Navy doctors he was despondent at the long delay in getting his medical discharge from the Navy. It meant he was stuck in what he considered a dull job as a military security guard. He was sick over the abrupt end of his Navy career. He was lonely for his wife, Leslie. And he was worried about having to support both households until his medical discharge.

He later denied to doctors that he tried to die by suicide. But that night, May 28, he took a Xanax and washed it down with three shots of whiskey. In a fog, he called Don. "Dad, I'm not doing well at all. I have an addiction. I want to stop but I can't," Don later recalled him saying.

Don didn't know about the whiskey, but he was deeply worried. "Are you high now?" he asked. "Yes," Joshua admitted. Don knew that reading Joshua the riot act now was not the best way to handle the situation, a lesson he'd learned in dealing with his wife's addictions. "Is there someone there with you?" he asked." "Yes." "Put him on the phone," Don ordered, and asked the friend -- whose name he does not recall -- to get Joshua to Portsmouth naval hospital's emergency room.

From there, he was put into the Navy detox unit in Portsmouth's Ward 5. His records show he was diagnosed with depression, thoughts of suicide, addiction to benzodiazepines and opiates, and panic attacks.

Don and Emily came to see him during the 11 days he was in detox. "I wanted to make sure he was there and safe," Don said. But when he pleaded with Joshua to acknowledge to Navy doctors the full extent of his drug problem, Joshua told him: no way. "He was afraid he would lose everything he had worked so hard to earn," Don told me. "Respect, rank, honorable discharge, benefits -- all of this weighed heavily on his mind."

On June 8, Joshua was discharged with a referral to the Navy's Level III substance abuse rehab program.

But he didn't go to rehab, because there was no space, Don said. Instead, Joshua went back to the townhouse, back to his dead-end job, back to his addictions. His Navy buddies were gone, deployed overseas or stationed elsewhere. "I tried calling him from Bahrain a few times," said one of Joshua's close friends, who asked not to be identified because he is still on active duty. "On the phone he sounded like he was good. I think he didn't want to worry me so he said he was doing good when he really wasn't."

They'd all had Navy suicide-prevention training, but some described it as meaningless, a computer exercise you had to click through in order to be granted time off.

It was 56 days before Joshua was admitted into the Navy's intensive drug rehab program at the Portsmouth naval hospital. In pre-admission exams he tested positive for benzodiazepine, opiates and cocaine, according to notes taken Aug. 4 by William C. Rodriguez, a Navy physician. Joshua admitted to having thoughts of suicide "over the past few months," but "he denied any active plans or intent to kill himself."

Joshua's growing drug use between detox and when he checked into drug rehab on Aug. 4 was not the Navy's fault, it said in a statement to The Huffington Post. It said a delay between detox and rehab is "typical," and patients can choose to participate in outpatient care while they wait. "However, patients cannot be compelled to participate in this care, particularly since care is ineffective without the patient's cooperation in their [sic] recovery," the Navy said.

He was not tested for drug use during that period because "such testing cannot be employed if the patient is not complying with their [sic] treatment plan."

In other words, a potentially suicidal drug addict on active military duty cannot be asked to submit to a urinalysis if he is using drugs.

Whatever happened in the Navy's five-week drug abuse rehab program -- and the Navy would not release those records -- it didn't take. Later that fall, Elliott came back from deployment and was disappointed to find that Joshua had taken up drugs again after his treatment. "I knew he was still using," Elliott said. "I tried reaching out to him and hanging out as much as possible, but he didn't want to go out and do things. He was always by himself, he just wanted to stay home."

Elliott remembers rushing Joshua to an emergency room several times because he was suffering withdrawal symptoms when his supply ran out. Finally, he said, he confronted the emergency room staff, telling them Joshua had a severe drug addiction.

Nothing, he said, was done. "How did that information not get passed on, that he was in the ER because he's having withdrawal from opiates and he's active duty? There should be no ifs, ands or buts about this -- the guy has a drug problem. We need to take care of this," he said.

At some point that fall and winter, Joshua started using heroin.

"I thought rehab would take care of it," Don said, referring to Joshua's addiction. He thought the birth of Joshua's daughter, Jayden, in September, would change Joshua's life, help him kick drugs. "When you hold her for the first time, you're going to love her so much -- just like I loved you when I held you for the first time," Don told him. "And he said, 'Dad, you were right,' he absolutely loved her," Don said to me.

"And he said, 'Dad, you don't have to worry because the Navy is going to drug test me all the time so it would show up.'"

"That made sense to me," Don thought, "because he's a known drug abuser so they would keep an eye on him."

Joshua went back to his old job, staring at security cameras at Oceana Naval Air Station in Virginia Beach. He was bored to tears, he told Don. Anxious to get on with his life, but stuck until the Navy processed his discharge. Going home occasionally to hang out with Andrew and Emily and check in on his mom.

She died Feb. 10 of colon cancer. The family, Don said, "was in bad shape." A memorial service was held two days later in New Jersey. Joshua had to be back on duty that Monday, Valentine's Day, a traditional family holiday when the Lipstein clan would gather. "My heart sank for him, knowing he had to leave," Don said. "Here he's leaving his wife and daughter, family -- all the people he loves the most, after his mom's memorial service, going back to a job he hates, living on a couch in someone's house -- ''

"I thought, 'We gotta get the Navy to release him.' That's what I'd been praying for since I found out what he was doing there. It just kept getting pushed back, the medical board. He'd say, 'Dad, they take forever,' and I'd say, 'Josh, it's gonna happen, we will get you home.'"

"When I looked him in his eyes that morning," Don said, "I thought, we have to get him home."

On Feb. 26, Joshua was taken by ambulance to the Sentara Bayside Hospital emergency room in Virginia Beach, complaining of panic attacks and chest pain. In the hospital's record of that visit, the section on "drug use" is marked "no." He was given a prescription anti-anxiety drug, Ativan, and sent home with a handout advising him to "use the Ativan as needed for anxiety ... avoid caffeine, benadryl and other over the counter medications. Avoid alcohol."

Ativan is a benzodiazepine, a common antidepressant to which Joshua had become addicted, according to Navy medical records. Its effects are magnified by alcohol.

Two weeks later, in early March, Joshua came home for a quick visit. He admitted to Emily that he was doing heroin. She was furious, reminding him that when their mom was doing heroin he said he'd never do it. They had a big fight; Joshua smashed the car windshield.

When Emily told her dad that Joshua was doing heroin, he was horrified. "I thought, the Navy isn't helping us," Don said. "How could he be passing his drug tests?" But he knew he had to do something. On the morning of March 15, he called a friend, a drug abuse counselor. He said he didn't want to make things worse between Joshua and Emily; could the counselor talk to Joshua without mentioning the heroin? She agreed.

Hours later, Leslie called with her frantic warning, setting in motion the flurry of final calls.

‘DROP THE SHAME’

Joshua's former commanding officer, Cmdr. Gary Leigh, came to the military funeral in Wilmington, where Joshua lay in an open casket. Leigh bent over and tenderly straightened his service ribbons.

Petty Officer Lipstein, the Navy concluded, "was under a significant amount of stress due to separation from his wife, reoccurring panic attacks, depression, a long term addiction to drugs, the death of his mother, brain surgery, loss of hearing, and a likely medical separation from the Navy."

"Looking at the evidence, his mental capacity was diminished at the time of his death, and he was not able to comprehend the nature of his actions and, therefore, cannot be held mentally responsible for his actions," wrote Navy Lt. Cmdr. Felix L. Hopkins of the Oceana Naval Air Station, who conducted the investigation.

After Joshua died, "I was in a frozen state," Don told me one day as we sat in his car in a parking lot outside Wilmington. He wore a polo shirt emblazoned with the logo of Navy Riverine Squadron 1. "I was in a state of shock for probably three months. There is a tremendous amount of loss, pain and guilt, shame, anger."

A Navy casualty assistance officer gave Don a batch of material after the funeral, including a brochure from TAPS, the Tragedy Assistance Program for Survivors. It provides peer-based emotional support for those who have lost loved ones due to their military service, connects survivors with grief counselors and other resources, and offers seminars and retreat camps for kids.

Don called and was put in touch with a trained survivor care team member. She was a good listener and he talked, slowly over the months absorbing the facts of Joshua's life and death.

As he began to thaw, Don came to understand some things about the suicide of his son. One was to drop the shame. Stop pretending it didn't happen. Celebrate the life that was. "My son died by suicide, but I loved him during his lifetime," he said. "He lived an awesome life. He was a great kid. People saw him as a shining star. I can't help but think of all the gifts he left us, Leslie and Jayden and the whole family. We are very close."

Don is now a peer mentor coordinator with TAPS, training other suicide survivors to approach newly bereaved family members to offer a friendly ear and other resources.

"The best thing for those who have lost a loved one to suicide -- and for the rest of us -- is to talk about suicide, he said. "Give it some attention. We have to get rid of the stigma of PTSD, depression, substance abuse. We have to talk about it or we're not going to be able to fix it."

"A lot of us [suicide survivors] get stuck in our shame," he said. "I just met a couple whose son died six years ago and they have never been able to talk about it. But talking about it helps people who struggle with the shame, and if you don't deal with that, the shame will eat you up."

He also learned how to move on. "I will always miss my son and love him, but I don't want his death to define my life," he said.

He began to understand that he would never comprehend precisely why Joshua took his life. That he couldn't play what-if: what if Joshua's Navy buddies had been around, what if his drug use had been detected earlier, what if his mother had not died...

"I don't think the military should be blamed completely," he said. But he did allow that "there were things the military could have done to help make it less traumatic for guys coming back and trying to get back into civilian society."

"They spend a lot of time to train them to be mentally and physically tough. But we don't do anything to reprogram them back. The training is making them tougher and tougher. But how do we train them to be soft again?"

CORRECTION: This article has been edited to clarify the timeline of events surrounding Joshua's death.

This article is part of a special Huffington Post series, "Invisible Casualties," in which we shine a spotlight on suicide-prevention efforts within the military. To see all the articles, blog posts, audio and video, click here.

For a review of warning signs someone may be at risk of suicide, click here. For a list of resources to get free and confidential help, click here. If you or someone you know needs help, call the national crisis line for the military and veterans at 1-800-273-8255, or send a text to 838255.

This story appears in Issue 67 of our weekly iPad magazine, Huffington, available Friday, Sept. 20 in the iTunes App store.