What if what is outside a school's windows is as critical to learning as what's inside the building? A fascinating new study of high school students in central Illinois found that students with a view of trees were able to recover their ability to pay attention and bounce back from stress more rapidly than those who looked out on a parking lot or had no windows. The researchers, William Sullivan, ASLA, professor of landscape architecture at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and Dongying Li, a PhD student there, reported their findings in the journal Landscape and Urban Planning.

Sullivan and Li argue that "context impacts learning. It is well-documented, for instance, that physical characteristics of school environments, such as lighting, noise, indoor air quality and thermal comfort, building age and conditions all impact learning." However, schools' surrounding landscapes have been too long overlooked for their impact on learning, and it's time to understand what campus greenery -- or lack thereof -- means for student performance. Research studies to date have had relatively small sample sizes. While these studies point to encouraging correlations or associations between improved student performance and access to nature on campus, Sullivan and Li argue that up until their study, no causal connections have been proven.

Looking at the effect of views of nature on both cognition and stress recovery, they test two theories: attention restoration theory and stress reduction theory. According to their report, attention restoration theory posits that "people use voluntary control to inhibit distractions and remain focused, and this capacity to remain focused fatigues over time." But the theory also contends that even just a short period of time in nature (10 minutes or so) can renew our cognitive capacity to pay attention. Nature does this through its ability to engender "soft fascination" that doesn't demand all of our attention, just enough to enliven us. Stress reduction theory looks at how nature supports psychological and physiological recovery, including lower blood pressure and levels of stress hormones.

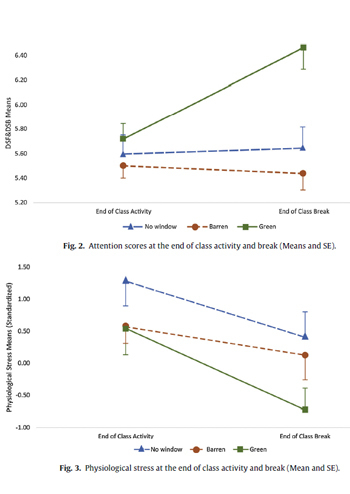

In Sullivan and Li's study, a third of the 94 students, equally male and female, were each randomly assigned to a classroom with either no windows, a window view looking out on a barren landscape, or a window view looking out over greenery. They were all put through about 30 minutes of classroom exercises. Their stress and cognitive states were tested in the beginning to set a baseline, at the end of the classroom activities, and then again after a 10 minute break after the activities. Researchers used both standard questionnaires to test stress and attention levels and various tools to measure their physiological responses to stress, including heart rates, body temperatures, and skin conductance.

After the students had completed 30 minutes of classroom activities, the researchers found the window views of greenery had actually no impact on students' ability to pay attention or their stress levels. However, at the end of a 10 minute break after the activities, the researchers discovered those who had a green view bounced back, attention-wise, and became less stressed -- this group "performed significantly better on standard tests of attention and showed significantly greater stress recovery than their peers who were assigned to classrooms without a green view." They think this is because during the classroom activities the students were too busy focused on what they were learning. Only when students with green views had a chance to take a break was their "involuntary attention" engaged while looking out the window. Only then did they receive the restorative benefits of looking at the trees.

Sullivan and Li say they found a causal relationship: "green views produced better attentional functioning and stress recovery." Furthermore, viewing nature helps both cognition and stress recovery, but through separate mental pathways. In other words, nature's ability to help us recover our ability to pay attention has nothing to do with whether we are stressed out or not, but nature, separately, also helps us recover from stress. (To learn more about this aspect of their research, read the study).

What's important for designers, school principals, and educational policymakers is that this is yet another promising study that points to the benefits of exposure to nature for school students. Sullivan and Li argue that new schools, which are often placed at the "urban-rural fringe" need to be sited where there are a lot of existing trees, and, if that's not possible, trees and shrubs need to be added. New schools should also be designed so they maximize views of trees and greenery from the inside; and existing schools retrofitted to improve the connection to nature. As Sullivan and Li argue, "architects should work to ensure every classroom has views of green space. Landscape architects should consider the location of classrooms, cafeteria, and hallway windows in the development of their campus design."

These changes to schools could be more cost-effective than "most interventions aimed at relieving stress (e.g., emotional skill building, anger management, positive behavior programs). Placing trees and shrubs on the school ground is a modest, low-cost intervention that is likely to have long-lasting effects on generations of students." To add, lots of schools encourage student environmental groups to engage in volunteer community service. Why not involve these students in greening their own campuses and teach them about the value of nature at the same time?

As with any study on the health benefits of nature with a relatively small sample size like this, there are priming issues. And Sullivan and Li acknowledge this: "one limitation is that we could not take into account students' interactions, physical activities, and their immersive experiences out on the school ground during break, or their exposure to green space during physical education classes or after school. This limits the ecological validity of the findings."

What's needed is a large-scale, longitudinal, government-financed study that looks at the benefits of nature across all critical dimensions, but, until then, here is another study that points to the positive effects of nature on cognition and stress recovery, this time in an educational environment.