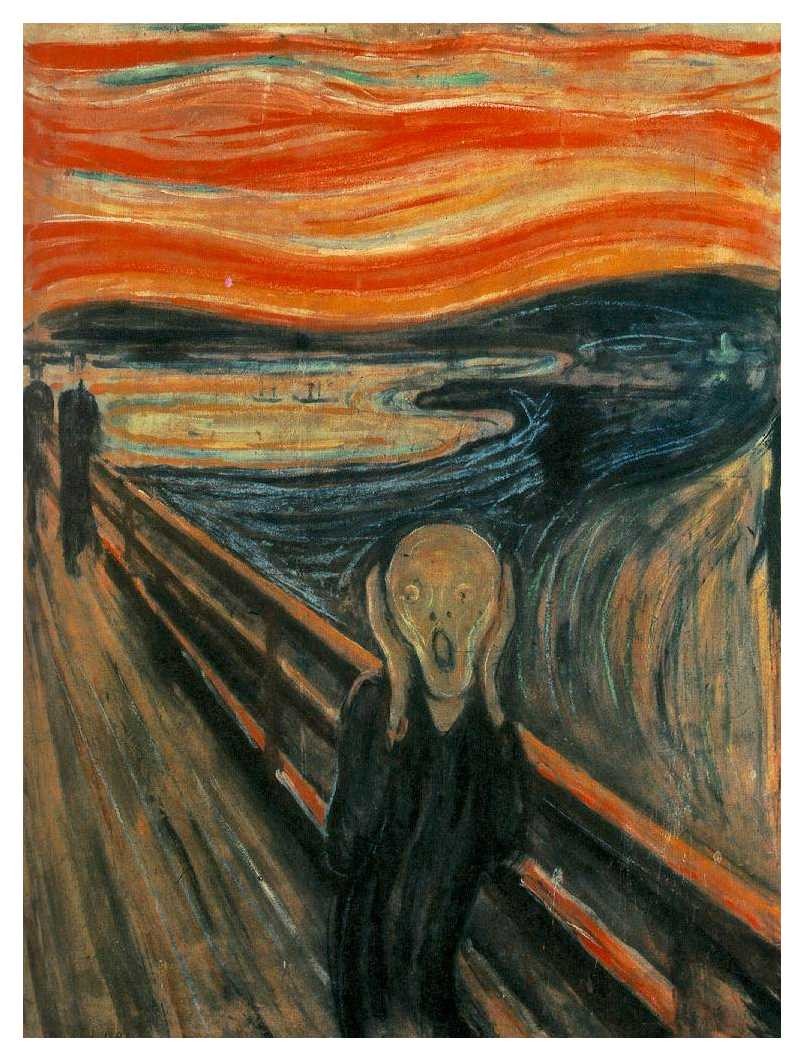

The horrible nightmares. An American soldier serving in Iraq recently wrote, "Last night I dreamed I was flying in a Blackhawk to another FOB and blood was covering the seats and the floor of the bird. There was so much that I was scooping it out the door with my hands. It's starting to affect my sleep a lot."

Nightmares are one of the most debilitating consequences of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) affecting 70 to 87 percent of patients suffering from the psychological trauma. Fortunately, a surprising new treatment uses an old medicine to stop them.

Sleep is essential for our health and wellbeing, and getting rest is fundamental and essential to recovery from any illness or bodily stress. Hallucinations, depression, and anxiety from sleep deprivation severely impair mental function to the extent that even simple tasks, such as talking or driving, can become a challenge. Sleep deprivation is an instrument of torture, but in people suffering PTSD it is an uncontrollable, self-inflicted torture. Terrorized nightly by horrific dreams that reopen the psychological trauma, PTSD patients suffer chronic sleeplessness, and as a result they cannot escape the self-destructive cycle of chronic fatigue, depression, helplessness, and fear. Psychiatrists empty the drug cabinet in a trial-and-error search for a medicine that will bring relief to people with PTSD. Everything from antidepressants, anxiolytics, antipsychotics, sedatives, to mood stabilizers are prescribed for PTSD. Now there is a surprising new approach: grandma's high blood pressure medicine.

A connection between high blood pressure and nightmares terrorizing people with PTSD seems odd at first, until you consider the body's natural response to stress. The first switch thrown in the body's fear response jump-starts the heart rate powering a surge in blood pressure. This familiar adrenalin-fueled boost is the body's way of revving up all systems for the "fight or flight" response to handle any life-threatening situation. The high blood pressure medicine, prazosin, dampens adrenalin's effect on the heart and blood vessels by blocking receptors for the hormone. This old medicine has become the newest approach to treating PTSD. Studies are still underway, but the data thus far show that 75 to 8- percent of PTSD patients who try prazosin stop having nightmares and sleep through the night with normal dreams.

But how could reducing blood pressure have any effect on nightmares and break the vicious cycle of reliving horrific memories of traumatic events? The answer is that adrenalin's effects are hardly limited to our cardio-vascular system -- adrenalin also has a powerful effect on the brain.

To understand how adrenalin and high blood pressure medicine could affect nightmares you must first consider how our brain stores memories, because vivid memory of the traumatic event is what triggers the nightmares in people with PTSD. Contrary to what most people think, memory is not about the past, it is about the future. Memory is nature's way of giving us a competitive advantage should a similar situation in the future arise in which the previous experience could be helpful. "I'll never touch that plant with three shiny leaves again!" (poison ivy). The trick is to quickly and accurately predict which experiences will be important to remember in the future and which can be discarded. But how can the brain predict the future?

Memory is selective. "Where the heck did I park my car?" is the price we pay for the far worse alternative of recording every minute of our life in permanent memory. "Remember that great parking spot we had at Wal-Mart in 1997?" Who needs that! But if you park in the same spot every time, you will not forget where you parked. Repetition moves short-term memories into long-term memory. The brain is wired to assume that any experience that is encountered repeatedly is likely to have future value, and so the repeated experience becomes filed in the brain's permanent memory bank. Repetition is how we got the not-very-relevant (at the time) multiplication tables into our head when we were children so that we could exploit them to advantage as adults.

But some events get seared into memory permanently after only one experience -- traumatic events. "I'll never forget how that pick-up truck backed into us when we were parked next to the shopping carts in the Wal-Mart parking lot in 1997." Any truly life-threatening experience will never be forgotten. The adrenalin surge accompanying the trauma is what marks an experience as life-threatening. Neural circuits in our brain are stimulated by adrenaline to encode the emotionally-charged event into permanent memory. Even the small details surrounding the experience, which would normally have faded in minutes, are retained -- "The truck was missing one hubcap."

It is the fundamental mechanism of memory that captures people with PTSD in perpetual fear. The memory of the traumatic event is unforgettable because the stress and adrenaline of the experience engraved it permanently in memory, and the nightly repetition of the event in nightmares reinforces the memory like a stuck record, preventing them from getting past the event. Blocking the effect of adrenalin with the high blood pressure medicine prazosin breaks the cycle.

A similar high blood pressure drug, propranolol, works the same way as prazosin, and it is being used to "erase" traumatic events from memory. Doctors ask the patient to recall the traumatic event that caused their PTSD while the adrenaline response is dampened with the medication. The painful memory loses its association with danger when the adrenalin signal is suppressed, and it begins to fade.

This forced recall to erase traumatic memories in the clinic re-enacts what happens naturally in our head every night at rest on our pillow. Recent research shows that the decision about what memories to keep and which to discard is made offline as we sleep. As we sleep our brain unconsciously sorts through our daily experiences, associates them with other memories, and decides which ones to discard and which to keep. So using high-blood pressure medicine to relieve nightmares and dampen the horror of traumatic memories, which seems so odd it first, makes good sense in light of how the brain uses the past to predict the future -- the mechanism of memory.

Note: Do not take any medication without consulting your doctor first.

References

Berger, W., et al., (2009) Pharmacologic alternatives to antidepressants in posttraumataic stress disorder: A systematic review. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry 33: 169-180.

Fields, R.D. (2005) Erasing memories. Scientific American Mind November 16:28-37

Fields, R.D. (2005) Making memories stick. Scientific American 292 (February), 74-81.

Fontaine, S (2009) Blood pressure pill slays nightmares. The Washington Post, Dec. 31, 2009, p. A15.

Miller, L.J. (2008) Prazosin for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder sleep disturbances. Pharmacotherapy 28: 656-666.

R. Douglas Fields is author of The Other Brain a new book about the recent discovery of a non-electric part of the brain formed of brain cells called "glia".