The film Nina starring celebrated actors Zoe Saldana (Nina Simone) and David Oyelowo (Clifton Henderson) is a film in search of itself. The life of legendary singer Nina Simone is one that is marked by triumph and tragedy. It is the life of a southern black girl born into a de facto segregated world, constantly reminded of her second-class status through laws and constant mistreatment, based solely on the color of her skin. Nina Simone was much beloved by fans and musicians not only because of her tremendous musicianship (classically trained), command of varied musical genres (jazz, blues, opera), beautiful voice and beautiful mind, but also willingness to use her music and public platform to speak out against the injustices against blacks in the United States and abroad at a time when it took courage and bravery to do so. As is the case with many who grew up in apartheid America, Simone self-medicated her way through segregation, physical and emotional abuse, eventually settling in Europe, causing strain in her professional and familial relationships along the way.

The complexity of Simone's story is lost in writer-director Cynthia Mort's first feature film, where she boldly goes where no first time feature filmmaker should probably ever go, telling the story of an iconic figure whose life experiences and activism are central to her memory and identity. Simone is revered by critics and fans because of a willingness to be true to herself, at all costs, and to discuss painful issues like colorism and discrimination in her music and public life. Simone's vulnerability and strength, which were on full display in her artistry, are missing from the film, which attempts to give audiences a peek into Simone's turbulent life during the 1990s.

Mort explores Simone's life as an ex-pat, whose return to the United States is marred by mental illness and the discovery she has been financially exploited by her record label. Simone's meeting with her manager Henri Edwards (Ronald Guttman) to discuss her missing money spirals out of control and the "High Priestess of Soul" ends up in an insane asylum under the care of Clifton Henderson (Oyelowo), a nurse who looks out for her. Simone and Henderson flee the asylum and the United States and head to the south of France, where he becomes her caretaker/manager. Saldana does a solid job of capturing Simone's whimsical and explosive nature although she struggles with maintaining Simone's distinct style of speech. Oyelowo is convincing as Clifton, Simone's caretaker who eventually becomes her friend, confidant and manager, even though his performance feels constrained. Perhaps it is because Saldana and Oyelowo lack the on-screen chemistry needed to give greater life to Simone and Henderson's emerging and intense friendship, that the weight of their friendship is never really felt or conveyed.

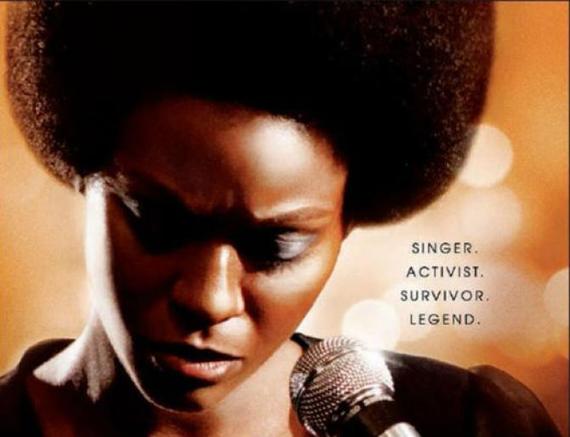

While the performances are decent, the film suffers from more problems than the much, publicized make-up job gone wrong in attempting to physically transform Saldana into Simone. Despite title cards, the time period of the film is never clear because the narrative and stylistic elements are not reflective of the 1990s. Although some of the fashions are fabulous, they look more reflective of the 1970s than the 1980s or 1990s. When Simone visits Clifton's star-struck family (Ella Joyce and Keith David) in Chicago in the 1990s, the wardrobe and set design are more reminiscent of the 1970s than the 1990s, not to mention hairstyles and cars driven in the scenes. The film is hard to comprehend and follow because it is visually anachronistic, particularly as it relates to narrative elements. Mort attempts to make up for the disjointed narrative by using interviews with a French radio journalist (Michael Vartan) to pull together a story and to add context, but the device doesn't quite work. Mort is obviously taking "a slice of life" approach to Simone's story, but viewers aren't quite sure which slice filmmakers are trying to share.

The most interesting part of the film is the relationship between Clifton and Nina, but even that story isn't fully developed. Audiences are never sure of what motivates Simone's self-destruction or Clifton's willingness to subject himself to her constant terror. One should not have to know Simone's real-life story in order to understand this fictional representation of this period of her life. Mort's cursory take on Simone's complex life lead Saldana and Oyelowo into performances that are inspired but don't connect with audiences because there's just not enough information about their connection. Reportedly Mort did not include Simone's family and close friends in her research process, and if that is the case, then it shows in this uneven film that could have been much better with more depth and substance in story and style.

There are a few bright spots in the film. The opening scene is strong and shows Simone as a child prodigy, insisting that her parents be given the dignity and respect that they deserve, during a critical performance in her childhood. Mort fails to continue injecting life-defining events into the narrative, relying too heavily on the interviews with the French radio journalist to give viewers insight into Simone's influences, which just don't cut it. Saldana actually sings covers of all of the songs in the film. Al Schackman, Simone's longtime guitarist and musical director, pulled together Simone's band members to cut 16 tracks of Simone's songs for the film. According to Schackman, the songs are performed "almost identical" to the ways they were performed when working with Simone. Saldana sings beautifully over the arrangement. The actress, who also serves as Executive Producer of the film, does a great job with the songs (she does not attempt to sing or sound like Simone), which demonstrates her conviction to the character and the telling of this story.

Mort and Saldana's close attention to the details of getting the music right for the film is perplexing when thinking of the lack of attention to detail with hair, make-up, set design and storytelling. Saldana does not remotely resemble Simone in real life or with this poorly done make-up job, so why even go there? Saldana's character isn't aged well in the film, again making it hard for viewers to remember what time period they're watching. It's too bad that what started out as a great idea about bringing the story of legendary musician Nina Simone to the big screen is literally torpedoed by the use of 18th century make-up techniques including a prosthetic nose, false teeth and what looks like a Party City Afro wig, which is distracting to viewers the entire film. The beauty of a great biopic (The Rose, Malcolm X, The Aviator, What's Love Got to Do With It, Sid and Nancy) is that you eventually forget you're watching the actors, which has to do with the performance as much as the attention to critical details like the look and feel of he characters and film.

While Oyelowo, who also serves as Executive Producer of the film, has escaped the scorn that critics have lobbed at Saldana for "allowing" Simone's style and physicality to be bastardized, the problem with the film is much deeper than a bad make-up job. It is wholly uneven and the devil is always in the details, especially when making a film about an iconic figure whose life and legacy is fresh in the minds of fans, many of whom watched the Academy Award nominated documentary, What Happened, Miss Simone? Nina leaves audiences asking, "What Happened to Miss Simone?" in the making of a film that has all of the parts of what should have been a great film, but falls into the trap of another clichéd tale of a self-destructive artist who "can't get out of her own way." Whichever story Mort chooses to tell, she merely scratches the surface of a story ripe for exploration and inclusion in the biopic genre. The devil is in the details; it is the lack of attention to important details that ultimately undermines this important film.

Nsenga K. Burton, Ph.D. is founder & editor-in-chief of the award-winning news blog The Burton Wire. A media scholar and critic, she is currently writing a book on race and gender in reality television. Follow her on Twitter @Ntellectual.