When President George W. Bush joined congressmen John Boehner, George Miller and Edward Kennedy to sign the No Child Left Behind Act in January 2002, he touted the moment as a bipartisan victory for America's children.

"Today begins a new era, a new time in public education in our country," Bush proclaimed in Hamilton, Ohio, as he signed the bill into law on Jan. 8, 2002. "As of this hour, America's schools will be on a new path of reform, and a new path of results."

But 10 years later, results matching Bush's rhetoric haven't yet arrived -- and the law itself is unlikely to change any time soon.

The latest rewrite of the 1965 Elementary and Secondary Education Act, NCLB was the first federal law to mandate regular standardized testing of students. These test results were to become a key lever in a school accountability system that divided schools into those that were making "Adequate Yearly Progress," and those that weren't. This type of school-based ranking would lead to increasing federal sanctions for schools, such as the mandatory setting aside of federal money for tutoring or allowing students to transfer to non-failing schools. By 2014, the law said, 100 percent of public schools would have students proficient in math and reading.

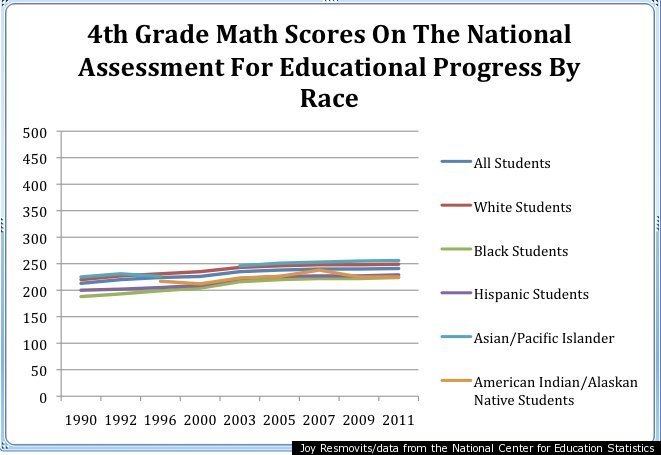

But as the sweeping education law reaches its 10th anniversary this Sunday, the jury is still out on NCLB's effects. While the law did shine a light on underperforming minority groups, scores on national standardized tests have seen little improvement and are still low, especially when compared to other countries.

Various parties, naturally, interpret the last decade of educational performance differently.

Those involved in NCLB's writing tend to characterize the law as a necessary but insufficient effort for an educational overhaul. Teachers say the law's narrow focus encourages them to teach to the test. Obama administration officials continue to call the law broken while hawking administration waivers, a solution that has yielded hodgepodge results. Meanwhile, the law has been up for renewal since 2007 -- and following a December flameout of bipartisan House talks and given the general congressional gridlock of a presidential election year, it's unlikely it will be rewritten before the next U.S. president takes his oath of office.

"It's [NCLB] not serving much purpose absent of revision," said Charles Barone, Democrats for Education Reform's director of federal policy, who helped pen the law a decade ago. "It's given us an awareness of how far we are and how far we can go. We need to learn from the experience and take it to the next level."

At the very least, by requiring states to participate in a national exam, NCLB forced an awareness of real performance. "Prior to NCLB, school districts and states told everybody that everything is okay," Barone said. "Kids getting A's and B's couldn't make it in college or the workforce. This was designed to bring some measure of reality to that picture."

As for NCLB's performance effects, according to Mark Schneider, a vice president at the American Institutes of Research who formerly headed the U.S. Education Department's research arm, NCLB seized on an existing accountability movement that yielded gains from the early '90s. "We had gotten evidence that the accountability movement was gaining traction and this was a good thing to do," Schneider said.

But overall gains in performance during the NCLB era are not large. "There were several significant flaws in [the law], all politically driven," Schneider said. He pointed to the law allowing states to define proficiency on their own. "We had the screws on the states for getting students educated to a level defined as proficient, but gave states an incredible out," he added.

Dianne Piche, a former Education Department official who helped write the law, said the lack of progress shouldn’t be pegged to NCLB itself. "The law is not a person," she said. "People will say it didn't do this and it didn't do that as if it were a school child or teacher. It's not a person, it's a piece of paper."

Some NCLB proponents argue the law hasn't ultimately delivered better results because sufficient support never arrived.

“When we negotiated the No Child Left Behind Act with President Bush, we all agreed that significantly more federal funding was needed to make the law work," said Sen. Tom Harkin (D-Iowa), who chairs the Senate's education committee. "President [Bush] didn’t live up to his side of the bargain. He never proposed anywhere close to the amount of funding that we had agreed to." Bush was not available for comment for this article.

NCLB has been up for renewal since 2007, and in late 2011 Harkin pushed a revised NCLB bill out of committee. The bill dramatically altered NCLB's accountability structure and received the support of teachers' unions.

But the NCLB revision didn't get support from education reformers and civil rights groups, and a logjam on the House side held up the process. Rep. John Kline (R-Minn.), who chairs the House's education committee, ended bi-partisan talks with Rep. George Miller (D-Calif.) in late December 2011. And while Kline plans to release his own Republican bills early this year, it is unclear how they could be joined with Harkin's in a conference committee.

Besides, as 2012 is a presidential election year, Republicans are disinclined to give Obama a legislative win.

But they inadvertently handed the president a political win. After decrying the effects of NCLB and Congress's holdup, Obama and U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan went forward with their own plan: They rewrote the law without Congress's help, allowing states that agreed to enact certain reforms to apply for waivers from some of the law's strictures.

The impasse in Congress was Obama's gain in another way: congressional inaction on NCLB ultimately got Obama his budget priorities for education. "By not passing reauthorization, they made him much more powerful in the appropriations process," Barone said. "He's getting money for these priorities, and he doesn't have to deal with the House or Senate."

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that the bill was signed in Princeton, N.J.; it was signed in Ohio.