This is Part 6 of the Timeline of Left Social and Political Art, 2001-2009. See Part 1, 1900-1944, Part 2, 1945-1966, Part 3, 1967-1979, Part 4, 1980-1989, and Part 5, 1989-2000, on Huffington Post.

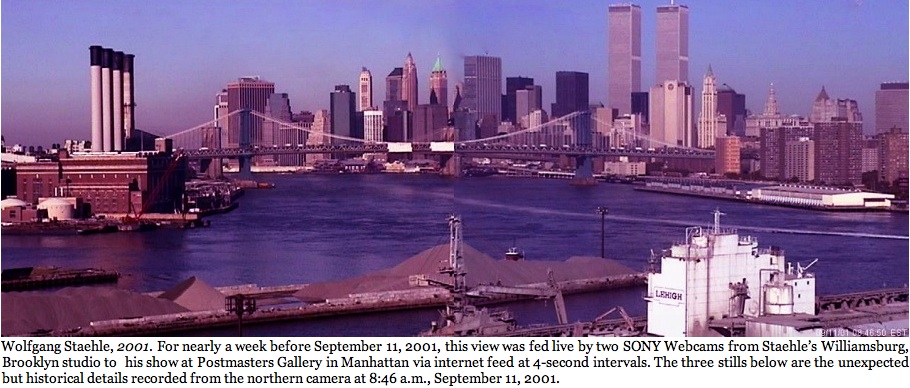

It was Thursday, September 6, 2001. I was at the opening of Wolfgang Staehle's show at Postmasters Gallery in New York. Projected onto the wall was a live, panoramic Webcam image of the lower Manhattan skyline stretching from the Brooklyn Bridge to the World Financial Center and fed from the artist's Williamsburg studio via the internet at 4-second intervals. I've long enjoyed Staehle's work, and I had included him in the last show I curated in New York some years earlier. But this projection left me wanting. The reason became apparent only minutes after I left the reception, when, as I began my walk home, I almost immediately faced the World Trade Towers. It wasn't that I thought of this precisely then, as much as I took the sight for granted as I usually did, which only reinforced my sense that there wasn't much value in watching an electronic vista dominated by landmarks that were within my sights most every day.

It wasn't the first time I'd underestimated Staehle's work. I didn't appreciate that he was the first to establish an internet artsite when he launched The Thing in 1991. Ten years later I realized my myopic neglect, but I couldn't have expected that lightning would strike twice, certainly not that I 'd be proven wrong so miserably within just a few days. Regardless of the qualitative range of Staehle's work, I've since come to regard the artist himself as something of an open portal onto the future. Still, there was nothing explicitly political about Staehle's work that day. It would become politicized, as is all art however remotely, by the context of history forced on it--only in this, the force of context would be as vindictive and annihilative as any human awakening to prior ignorance has ever been.

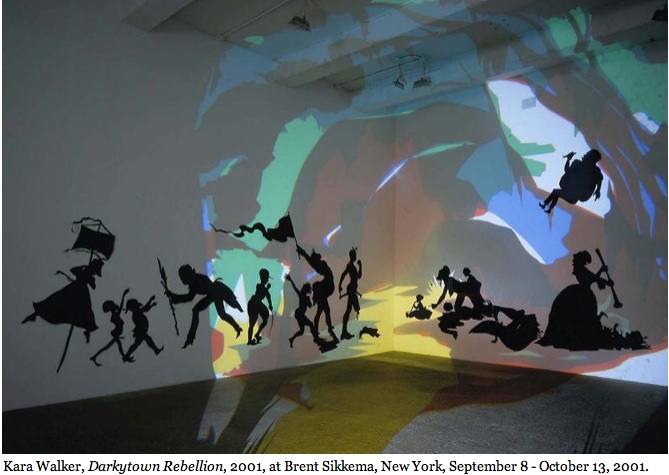

The last art I can remember seeing before September 11, 2001 was acutely political. Kara Walker's American Primitive, which opened Saturday, Sept. 8, at Brent Sikkema, in New York, thrust left politics on me at a time when politics were the furthest thing from my mind that year, and then only pertaining to domestic affairs. Even stirring shows like Kara Walker's were on their way to seeming status quo. It seemed a natural progression of events: The AIDS crisis, while not over, had been dramatically contained in developed countries. The Berlin Wall had been razed; the Soviet Union had collapsed; China was now in capitalist mode and in collusion with the "anti-revolutionary" West. The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda was underway; East Timor was liberated from Indonesia and had become the first sovereign state of the 21st century; the 1988 Palestinian Declaration of Independence in 2001 was recognized by some 60% of the United Nations membership. The U.S. economy was not only robust, the country had the first federal budget surplus since 1969. In the art world, women and people of color were being shown in the white men's galleries. In liberal circles on the two coasts, everyone had a new queer friend or relative to boast of. Even the disappointment over Al Gore's refusal to challenge the Supreme Court's ruling in Gore v. Bush, had by that time subsided. Politics hardly seemed to present an international cause to put it on the radar of art.

Yes, the Somalian and Sudanese Civil Wars were raging, and Gaza was more hell on earth than ever, but little news about these conflicts was being aired to Western audiences. We were high on our economic prosperity, and assuaged by the insularity engineered in the new monopolistic buy out of our news media sources. (In 2000, The Media Monopoly reported that only 6 corporations owned the vast majority of news media in the U.S., down from some 20 corporations in 1992, and 50 in 1983. Blogging, meanwhile, was only just beginning to penetrate the mainstream consciousness. ) All in all, the mood in America in 2001, and in the art world in particular, suggested that Left politics, or at least Leftist dissent, was on the wane.

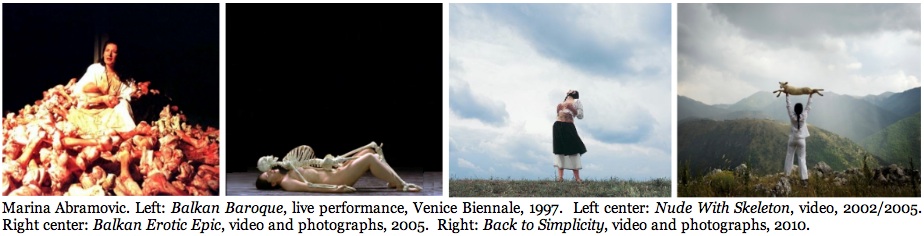

During that period of American apathy, there was at least one significant international artist who was politicized by the perceived political disillusionment of Americans. Marina Abramovic, who prior to the wars that tore her native Yugoslavia apart, was not noted for making an art of political commentary or dissent. Even during the first years of the conflicts, Abramovic claims to have felt too emotionally tied to the tragic and criminal events to respond to them in her art. By 1997, however, she released what would be the beginning of a tide of cathartic outpouring responding to her traumatized homeland that as of 2012 has still not ebbed. This phase of her production includes work, such as Count On US, that indicts the U.S. and the international community for not responding to the Balkan wars with the expediency or effectiveness that could have saved tens of thousands of lives and safeguarded as many women from rape.

My point is that American artists weren't focused on international affairs between the late 1990s through most of 2001 because our government and media weren't. It took an unprecedented attack on our soil by an enemy most of us had never heard of to refocus us abroad, and onto countries and peoples with whom our most politically-minded artists have been fixated ever since.

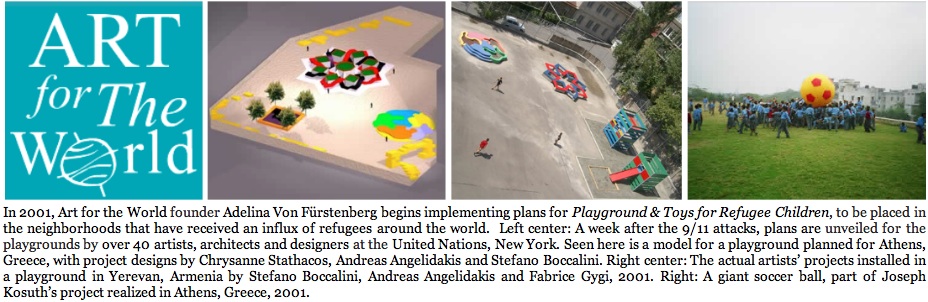

In my own life, art became entwined with my experience of 9/11 almost immediately upon the impact of that first plane with the North Tower. I can remember being awakened to that gloriously sunny morning by a tremendously loud engine overhead. The shadow of what must be the lowest plane to ever fly over my building darkened my view of the garden as it passed. Seconds later, there was a loud crash. I turned on the television and the news couldn't have come on in more than five minutes. After that I can only remember being on the phone with the people I knew who lived in the shadows of the World Trade Towers, all artists, some I had written on, and all safe. Then I remembered that a Swiss curator friend, Adelina von Fürstenberg, the founder of Art for the World, was in New York installing a show at the United Nations. We called her to warn her not to go in, fearing the U.N. would be another target. Art and artists somehow competed for my attention even that day.

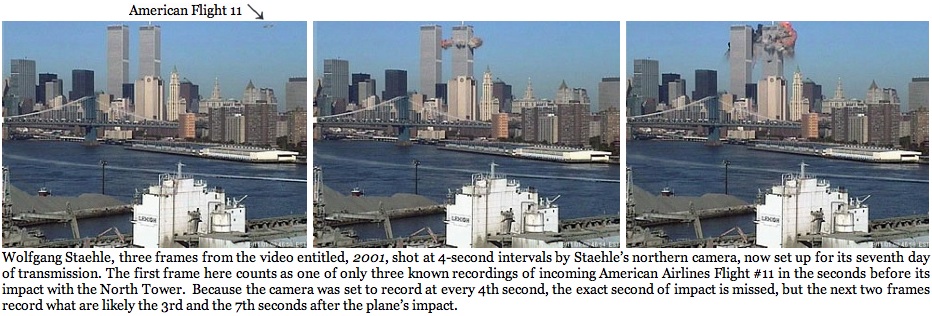

With all that we faced in New York that month, I'd largely forgotten about Staehle's show at Postmasters. It was only weeks later that I learned that Wolfgang had caught the last seconds of American Flight 11 before it's impact on the South Tower. It wasn't until five years later, as I read David Friend's book, Watching the World Change: The Stories Behind the Images of 9/11, that I learned Staehle was one of only three people known to have photographed the first plane. (Because of the video feed's 4-second delays, Staehle didn't capture the instant of the plane's impact.) Yet, as David Friend wrote: " At that instant, as evidenced by the time code in the lower right-hand corner of the frame, Staehle's cameras happened to catch ... the first salvo of the deadliest terrorist strike in American history, a series of attacks which would claim the lives of nearly 3,000 people in a coordinated assault by four teams of suicide hijackers from the extremist Islamist faction, al-Qaeda."

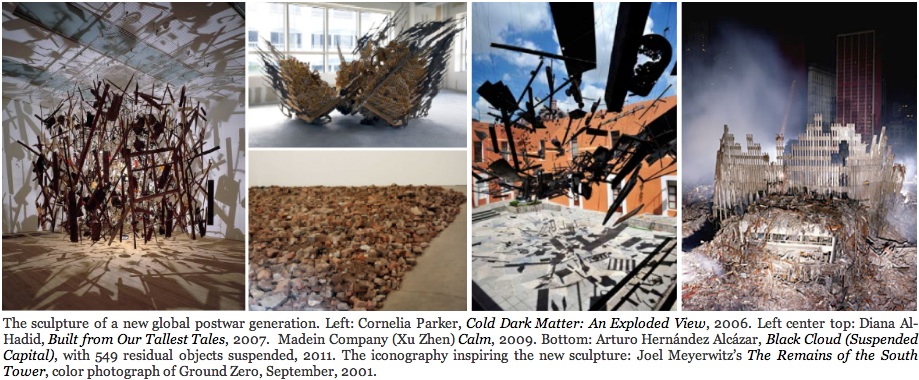

It seems remarkable to me now that there was so little art being made about 9/11 in the weeks, months, and years following the attacks, though it seems likely the dearth can be accounted for by the ceaseless stream of media coverage. Then, too, everyone had been transformed into an amateur photographer, what with cell phone sales having just begun to hit their stride. Today we all have our favorite 9/11 photographers, many of them professional and award-winning journalists and artists. There are the two "official' Ground Zero photographers, Gary Marlon Suson, reputedly the only photographer "permitted to document, side-by-side, with firefighters and rescue workers," and Joel Meyerowitz, who recorded for the Museum of the City of New York the changing scenery in and around Ground Zero. Among the artist photographers, the Spaniard Fransec Torres has emerged as one acutely possessed of a vision that is both understated yet penetrating.

Yet, in writing this, it strikes me as absurd, even obscene, to proclaim there to be official or leading photographers of 9/11. Despite their great talents, they represent special interests, commercial, aesthetic, political, that allowed them access to sites off limits to the rest of us who wanted, needed a glimpse to heal, or to simply satiate a gnawing need to belong to the human race. The events of 9/11 likely count as among the most photographed events of history, which is why only a democratic representation of photographs with no qualitative criteria presiding truly fits the historical, technological, and humanistic scale of the 9/11 attacks.

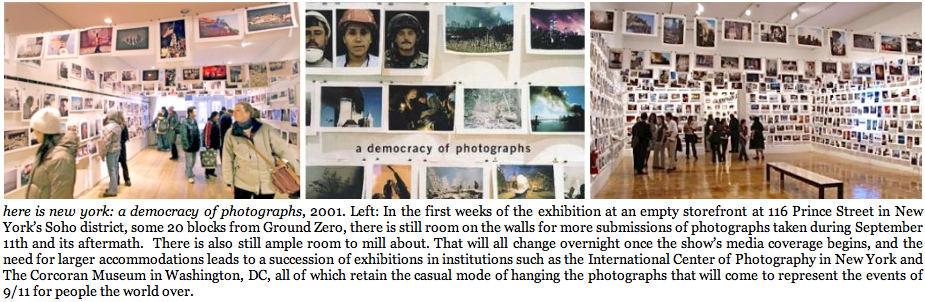

That is why that, for this writer, the show that best responded to the events and climate of 9/11 was the populist exhibition, here is new york: a democracy of photographs. Representative of the photography of anyone and everyone who possessed a camera that day and in the days after, here is new york opened on September 25 at 116 Prince Street, in Soho, with the first photograph of the World Trade Center, as people wished to remember it before the attacks, taped to the front window. Founded by writer Michael Shulan, who owned the empty storefront and offered it as a gallery space; photographer Gilles Peress; photographer Charles Traub, who as chair of the Photography and Related Media Department MFA program at the School of Visual Arts was able to secure the contributions of the students and faculty; and photography curator and editor Alice Rose George. Together the team publicly solicited photographs of September 11 from professional and amateur photographers alike. No one who wanted to make a submission was turned away no matter what the quality. In early October, orders for prints began to be sold for $25 each, with the proceeds benefiting the World Trade Center Relief Fund of the Children's Aid Society, various firefighters' funds, and the Soho Alliance.

According to the New York Historical Society, "Submissions were accepted onsite during gallery hours; an effort was made to take at least one image from each photographer." The images were displayed without captions, anonymously, reflecting the project's subtitle, "a democracy of photographs." The exhibition was anything but elegant and professional. The prints were all unframed and tacked to the wall, with many clipped to wires like clothes on a clothesline stretching along the upper walls and ceiling and through the middle of the space.

The public response to the show was overwhelming--thanks to the coverage it received in the New York Times and Village Voice, on World News Tonight, CNN, Newshour, The Today Show, Oprah, and Dateline, along with such world renown visitors as former President Bill Clinton. The mid-October closing was postponed. A constant stream of viewers swarmed to the tiny storefront, which seemingly couldn't hold more than a hundred people at a time, prompting long but patient and cordial lines waiting, and viewers exiting in tears. The show not only continued, it expanded into an adjacent storefront and the founders soon after established the project as a nonprofit organization. There may have been more professional, elegant, historically significant, avant-garde, and blue chip 9/ll exhibitions over the course of the last decade, but there were none as politically powerful as this show representing the photographer that everyman and everywoman has become.

The New York Historical Society goes on to report that in 2002, here is New York exhibitions of the same images were organized in Chicago, Washington, D.C., Houston, Berlin, Dresden, Dublin, and Tokyo. From February to June 2002, the International Center of Photography and the Durst Organization provided the New York show a new exhibition space at 1105 Sixth Avenue.

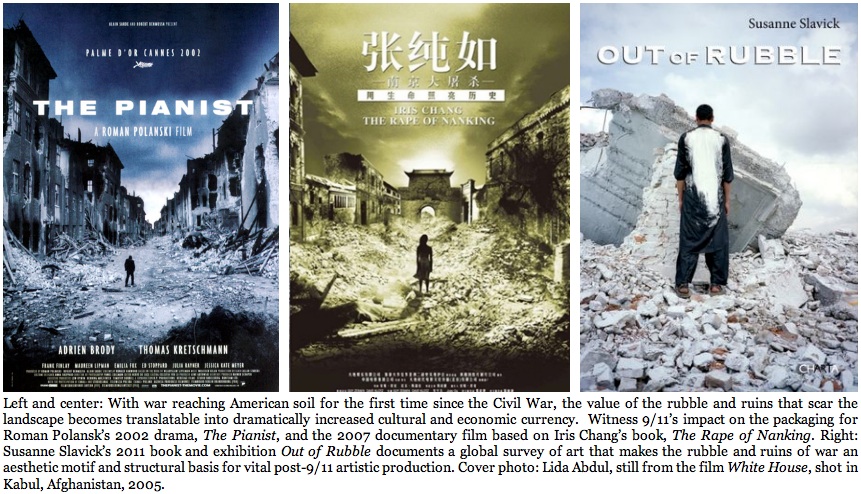

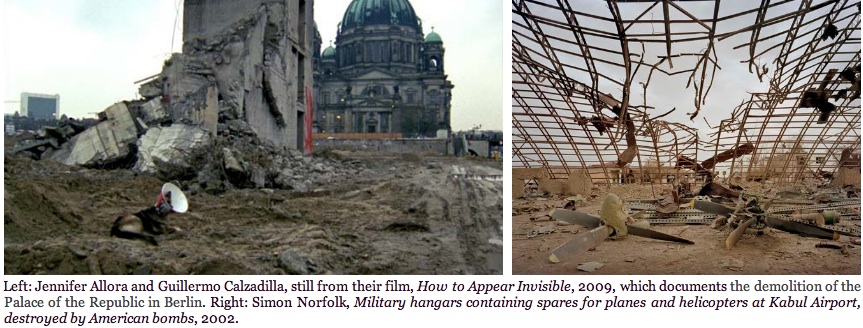

If there is a lasting mark that 9/11 has left on the art of the post-9/11 era, it is likely what artist and curator Susanne Slavick has drawn attention to as the aesthetic of rubble. And really it is the cumulative rubble that faces the many nations faced with the aftermath of war or economic downturns. In July, 2012, the journal Cultural Politics will feature my review of Slavick's exhibition and accompanying book. Suffice it to say here that the ruins of cities have at least since the Second World War supplied a visual and existential motif that informed the art of wartime. The difference after 2001 is that for the first time since the American Civil War, the rubble of war meant something real and tangible to Americans without leaving American soil. Rubble and ruins were made viable not only as thematic and visual motifs, but as the structural basis of art. This goes as well for artists working well outside the art world. Certainly the packaging for such movies as Roman Polanski's The Pianist and Iris Chang's The Rape of Nanking, and for that matter the scenes from the films being represented, have been aesthetically heightened by the post-9/11 empathy that American audiences now share with the world.

If there was little if any organized Left in the U.S. to offer opposition to the Congressional vote to enter Afghanistan and eradicate al-Qaeda, it's because the energies of the Left had become focused since the 1980s on personal and domestic politics. But suddenly personal politics seemed secondary to an act of war so spectaculary and horrifically achieved. The few voices that sounded out against the US foreign policies and covert funding of al-Qaeda that led to 9/11, notably such writers as Susan Sontag and Noam Chomsky, were loudly and overwhelmingly scolded even by the Left as unpatriotic and disrespectful to the 9/11 dead.

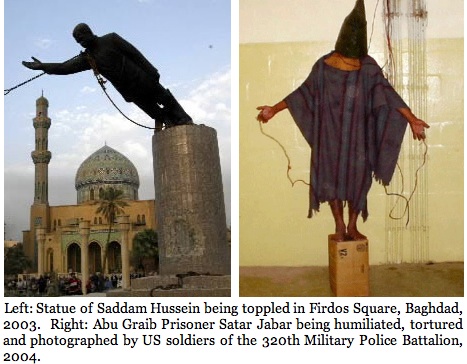

Then, too, the Left wouldn't have the same access to photojournalism in the two new US wars abroad that it had in Vietnam, thanks to the Pentagon's tightly-controlled policy of embedding journalists within the troops it approved. As a critic who sees journalistic photographers to be artists, good or bad, I missed the process by which news photographs in the late stages of the Vietnam War informed art practice both aesthetically and politically. Sadly, in Iraq, it took an obscene form of photography not by a photojournalist to provide the Left with the iconography it required to become energized--while dialectically transferring the opinion of ordinary citizens from their former pro-war stance to a revived, if cautious, criticism of American military policy and activities in Iraq and Afghanistan, especially regarding the use of torture and detainment.

The Christian Science Monitor's Nicholas Blanford best summed up the iconographic transfer that was accomplished with the release of the photographs of the torture and humiliation of Abu Ghraib prisoners. "If one image symbolized the US-led coalition's victory over Saddam Hussein, it was the toppling of the dictator's statue in central Baghdad last April. Yet that signal moment has been replaced by a simpler motif--a man wearing a ragged cloak, his head covered by a bag and his arms outstretched in a terrible, but unintended, parody of Jesus' suffering on the cross."

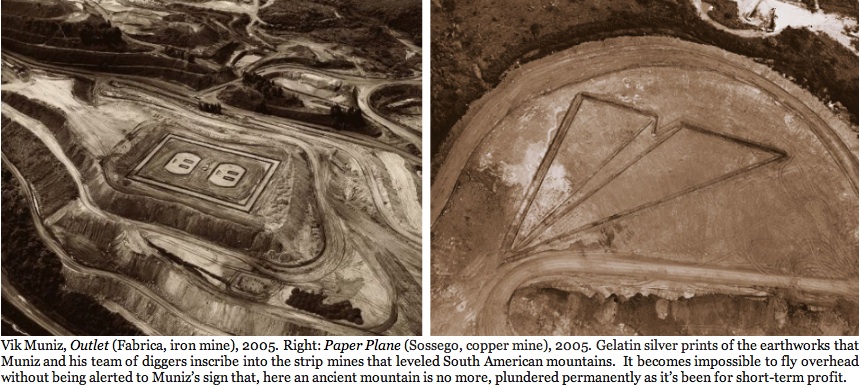

One Left political art agenda did continue on undimmed throughout the 2000s, no doubt because its healing of the earth is equivalent with the healing of humanity. The eminently pragmatic ecoart movement began to flourish in availing itself to problem solving in the tradition more akin to urban and park planning than to aesthetics. Conceptual art in the 1970s veered close to such a conversion but ultimately remained fixated on the art-for-art dictum. Today the philosophy underpinning ecoart is art for the ecosystem, with a greener eco sensibility growing into a global movement largely outside the market interests of the gallery and institutional art world. Having the renewal and maintenance of natural resources as its chief motivation, logic and structure, the new ecoartists redefine art to include whatever tasks are necessary to implement art as part of a sustainable ecosystem, including civic organization and education of the public.

One such organization is ecoartspace, founded in 1997 by California curator, Patricia Watts, as an art and nature center in development with a website and rapidly growing online network dedicated to art and environmental issues. New York City curator Amy Lipton joined Watts in 1999, and together they have curated numerous exhibitions, participated on panels, given lectures at universities, developed programs and curricula, ad written essays for publications from both the East and West Coasts. They advocate for international artists whose projects range from scientifically based ecological restoration to product based functional artworks, from temporal works created outdoors with nature to eco-social interventions in the urban public sphere, as well as more traditional art objects.

At the end of the 9/11 decade we can see a new global art agora that has over the last decade produced the progeny of a new breed of art collector and art institution ideologically nourished by decades of cultural cross-fertilization. Counted alongside collectors and institutions who favor traditional or national artists, buyers eager for global representations of art have become so numerous and so voracious they are generating an economic windfall that is so far showing resistance even in the face of volatile fluctuations in commodities, energy, credit, and currency around the world. Despite the ensuing recession, the steady incline in value and appeal of world art as the new "gold standard" proves idealism can and will fuel markets, especially when inflating the value of art and entertainment.

And yet, even in 2012, the mainstream of the art world lags behind the global markets despite the significant number of nations coming to play a significant role in the international market for contemporary and traditional art. Only in the last decade have the former centers of civilization come to realize that as we slept in the insularity of our dominance, the notion that art knows no borders―once little more than a hot house hybrid of idyllic theory divorced from real politics (and one conveniently forgetting the long history of autocrats and states issuing artistic agendas)―had been discreetly sending out roots to private collectors and institutions far outside the West. What with the vital and "new" international art markets emerging from New Delhi, Beijing, Abu Dhabi, and Dubai joining with markets not all that old in Moscow, Hong Kong, Taipei, Istanbul, Mexico City, and Tel Aviv, worldwide sales of art are rallying record highs.

The Left and its politics figure in on this globalization by ensuring the aesthetic and ideological offerings of the art markets remain as diverse as the artists and collectors wish them to be. It's now over two decades since some of us--critics, theorists, artists--called for a nomadic valuation and criticism of art--a valuation and criticism encouraging us to diversify the cultural terrain with the contributions of indigenous artists the world over. If there is a nomadic enterprise today, it is no doubt that of the consumption of culture; and if there is a nomadic profession, it surely must be that of the globally-attuned artist.

Because the world's many cultures offer so many models of reality and identity existing simultaneously, because there are so many societies and cultures converging in a global community, because discourse is being negotiated among them and because we are recognizing multiple histories of the world, we require a critical attitude that rides with the shifts in civilization's discourse. The best of today's artists and critics are ready to visit the models of any given community―ideological, spiritual, political, economic, technological, scientific, aesthetic―at any given time without obstructing communication or insinuating personal models on them. This doesn't mean that we must have expertise in a model or even accept it personally, only that we be ready to relinquish our dreams of domination for an acknowledgement of the world's diversity.

We've evolved cognitively, culturally, to the point where we've come to see that when two or more ideas conflict, the conventional temptation is to reconcile or oppose them. But nomadic criticism refutes that defensive reflex. There is no need to reconcile any one idea to any other, including the model of nomadism. We simply move among differences, using them when we need to, putting them on hold when we don't. The nomadic ideal doesn't position two or more models into opposition. We think only of two or more ideas as being opposed if we think that we hold a more comprehensive, singular, or foundational truth. Nomadism holds that there are no foundational truths, only shifting and contingent models that are as temporally relative as the conditions among individuals, communities, and environments that produces them. Artists have been indicating as much often without realizing it. Only now that we have gained a captive global audience and equally global contribution of artistic styles and ideologies, can the display of artistic diversity, like the biodiversity it stems from, be observed and expanded.

TIMELINE OF LEFTIST SOCIAL AND POLITICAL ART, PART 6: 2001-2012.

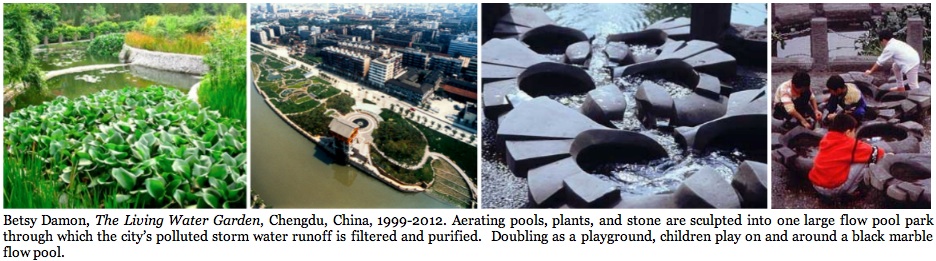

1999-2012: Among the largest and most celebrated ecoartworks made for the new millennium is Betsy Damon's Living Water Garden on the riverbank flowing through Chengdu, China. The hillside site provides a natural downflow of newly-filtering rocks, earth and plants that clean polluted storm water as it flows into the river. Damon has installed sculpted black marble and flow form pools throughout the park that in addition to aerating the water, makes a rhythmic oscillation of currents that effect an ecological art of sound, form, and visual patterns that can be physically interacted.

2001: The United Nations organization, Art for the World, founded in 1996 by Adelina Von Fürstenberg in Geneva, Switzerland, actively promotes Universal Human Rights through the advocacy of Pubic Art around the World. On September 18th, 2001, Playground & Toys for Refugee Children, curated by Fürstenberg, opened at the United Nations, New York, unveiling plans and designs by over 40 artists, architects and designers from around the world for new projects, playgrounds and educational toys to be presented to the neighborhoods of underprivileged children in Athens, Milan, New Delhi, London, New York, Paris, and many smaller cities, such as Yerevan, Aremenia. The artists invited to design the playgrounds included Vito Acconci, USA; Andreas Angelidakis, Greece/Norway; Sergio Augusto, Brazil; Carlo Berarducci, Italy; Bleue Roy, France; Stefano Boccalini, Italy; Andries Botha, South Africa; Daniel Buren, France; Paolo Canevari, Italy; Los Carpinteros, Cuba; Fabiana De Barros, Brazil; Silvie Defraoui, Switzerland; Dunning-Versteegh, Switzerland; Sylvie Fleury, Switzerland; Fabrice Gygi, Switzerland; Noritoshi Hirakawa, Japan; Pip Horne & Shirazeh Houshiary, UK; Alfredo Jaar, Chile; Soo-Ja Kim, South Korea; Joseph Kosuth, USA; Eva Marisaldi, Italy; Izumi Ogino, Japan; Maria Papadimitriou, Greece; Maria Carmen Perlingeiro, Brazil/Switzerland; Risa Sato, Japan; Teresa Serrano, Mexico; Edgar Soares, Brazil; Chrysanne Stathacos, USA/Canada; Haim Steinbach, USA; Vivan Sundoram, India; Nari Ward, Jamaica; Chen Zhen, China.

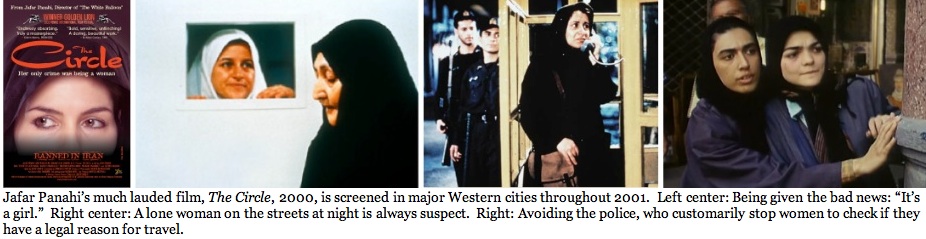

2001: Jafar Panahi's The Circle is screened in major Western cities to highly positive reviews. As the first film to fill a deep void in the West's understanding of women living in orthodox Muslim cultures, The Circle makes Panahi the most renowned director of the Iranian New Wave. Politically the film literally rotates around the issue of women's freedom in post-revolutionary Iran, literally in that it moves around a circle of women who must pit their wills against the ruling orthodoxy, returning in the end where it began with little or no resolution found. We never see resolutions, just women's attempts at escaping authority, finding respites in a day, contending with their devaluation. When one woman meets her limits, the film moves onto another woman at the outset of finding hers. These are simple affairs, such as who can ride a bus, who can attend university, who has a professional career, even who is free to walk down the street. Although male authority is oppressive, we also see that it isn't monolithic. In fact it is in the diversity we witness, in the freedom some women have in the face of other women's neglect, that we see how arbitrary the authority and its sources can be. As a consequence, however varied the audience, the more they become unified in their anger. As one critic has put it, The Circle is axiomatic in that "its political provocations tend to put us all on the spot and make us angry or defensive, sometimes both." See more about Panahi in 2010-2011.

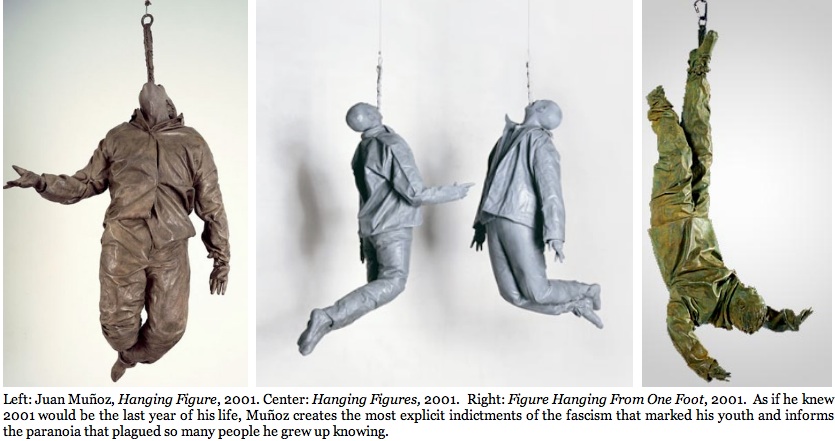

2001: Is it ironic that Juan Muñoz prematurely died of internal bleeding from an aneurism of the esophagus in the same year that his last works consisted of figures hanging from cables extending from the esophagus? What is certain, Muñoz himself professed, is that much of his work has accrued as memories of the years of his childhood and adolescence under the repressive Franco regime in Spain. Muñoz was 22 years old when Franco died, easily enough time for the seeds of angst and foreboding planted in childhood to grow into nightmarish visions resembling those of Goya's transplanted to a 21st-century detention camp or penitentiary for political prisoners.

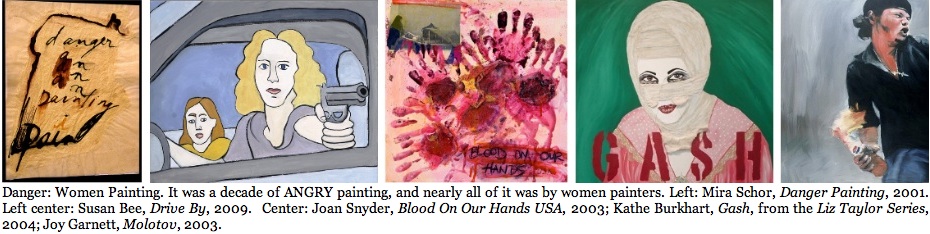

2003-2009: Mira Schor and Susan Bee, the Thelma and Louise of the Feminist Painting and Crit set, pose the biggest threat to male domination of the medium and criticism of painting in that they are critics as well as painters, and editors to boot, whose joint imprimatur has been pulsing out the feminist-left political art journal M/E/A/N/I/N/G since the mid-1980s. But Joan Snyder, Kathe Burkhart, and Joy Garnett are packing the heat just as heavy, what with their early-to-mid decade paintings aimed squarely against the Bush-Cheney-Haliburton War and Torture in Iraq, the petrol added to their feminist molotovs thrown into the art wars that try but never succeed to blow painting out of memory if not existence. It's not that irony doesn't figure into such work. In the pictorial painting seen here, irony of medium, source of imagery and intent figure in significantly. But all of these women are well aware that irony doesn't produce lasting political solutions, which are the larger priority.

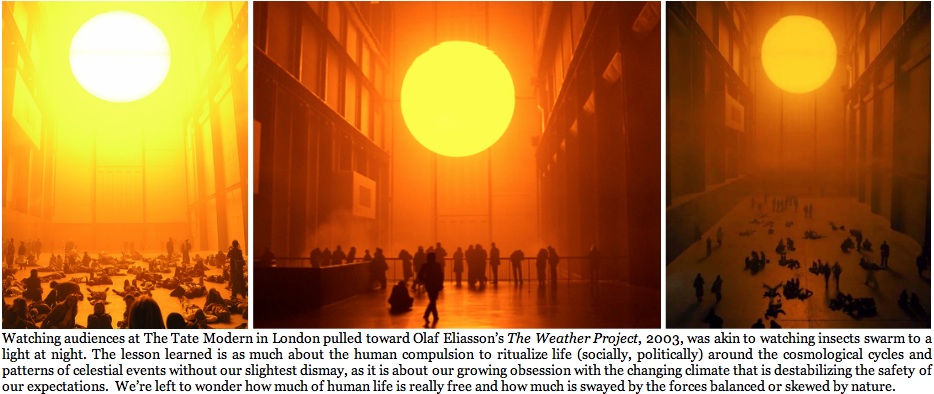

2003: Besides Olaf Eliasson's more obvious futuristic allusion to the culminating effects human populations have on weather, and the denial and debate that feasibly can one day escalate into warfare over which populations have control over weather modification, is the ancient root of politics that makes it akin to religion. Polis, the greek word for the people, is underscored in the reactions of audiences to Eliasson's 2003 Tate Gallery installation, lingering passively beneath the simulated sun despite knowing its end of days effects are entirely theatrical underscores the religious and theatrical aspects of politics.

2003: In the closing days of the Second World War, Nazi officials evacuated the small Helmbrechts concentration camp on April 13th, 1945 to escape the arrival of Allied troops. The 580 women concentration camp prisoners, a number who were Hungarian Jews, were made to march at gunpoint a 225-mile route leading from southern Germany through the occupied Sudentenland, now the Czech Republic. Ninety-five of the women died of exhaustion, starvation, or were shot by their guards in the last days of the European liberation.

On the occasion of the 53rd anniversary of the march, American artist Susan Silas traced the route on which the prisoners were marched. Covering the route as much as was possible on foot, and otherwise by car, Silas in 2003 commemorated the route in a series of photo inkjet prints. Beside showing us the striking, bucolic terrain withholding all trace of its sinister history (neither a sign nor a monument anywhere commemorates the women or the march), Silas' depictions of the contemporary route compose the closest approximation to experiencing the last views greeting the female Helmbrechts prisoners. Each image was then conjoined with texts taken from the diary entries that the artist made on the day that she took her photograph. Printed beneath each photo is the international news for that day taken from newspaper accounts and anchoring the image in the temporal and international context in which the real landscape was experienced. In this way, Silas maintains the reality in which she projects her life circumstances onto the tragic history of the women prisoners at the same time that she commemorates the family members she lost to the Holocaust.

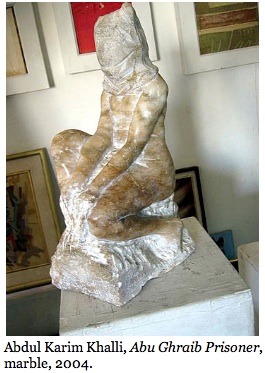

2004: As can be expected, news of the torture and humiliation of Iraqi prisoners at the Abu Ghraib prison was greeted with outrage by Iraqi artists. A protest exhibition at the Hewar Art Gallery, Baghdad, in 2004, prompted this work: the photo above is taken from the 15th installment of Steve Mumford's arousing 2004 "Baghdad Journal" that appeared on artnet.com in the first year of the Iraq War. The marble prisoner wearing a bag over his head is a direct descendant of Michelangelo's bound slaves.

Nicholas Blanford, Correspondent of The Christian Science Monitor, described the Hewar show in his June 15, 2004 column. "The Hewar gallery is a popular meeting place for artists and intellectuals, a place for them to sit shaded from the fierce noon heat by leafy trees, smoke cigarettes, and sip scalding glasses of tea. The leitmotif of the Abu Ghraib pieces of art is the hooded detainee. One artistic rendition is a torso and hooded head made of white plaster, splattered with red paint to simulate blood. Another structure of polystyrene and plaster depicts manacled feet and hands. Another is a thin human figure made from a single length of linked chain. Perhaps the most striking exhibits are the three sculptures by Abdel-Karim Khalil, a professional artist for 22 years. One of them is a foot-high rendition of the classic hooded figure with his arms outstretched. The other two are carved from blocks of yellow-veined marble. "It took me about 10 days to carve it," Mr. Khalil says. He says that many artists have found creative inspiration not just in the abuses at Abu Ghraib but also the general rigors of living under military occupation. "Some artists used to be neutral, but now there are artists, poets, and writers who have all reached the decision that the Americans are destroyers. It has given them a new sense of purpose in art," he says.

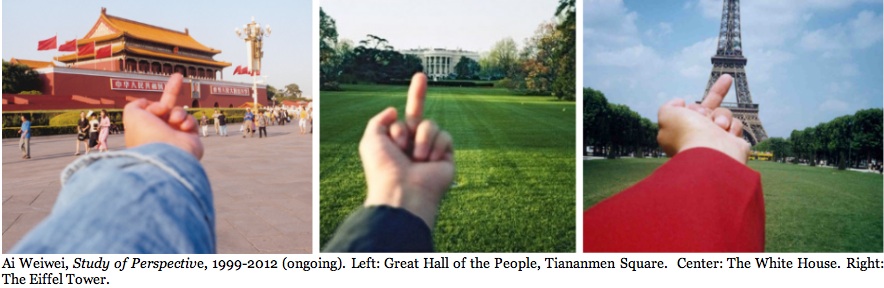

2004: Despite that Ai Weiwei spent a good deal of the 1980s living in New York, 2004 is the year that many New York audiences came to recognize the artist's versatility. The series that continues to garner attention, in part because it is continued with most all Ai's travels, is his Study of Perspective, begun in 1999. Despite its defiant humor denotating in the image of the raised middle finger aimed at icons of establishment power--Beijing's Great Hall of the People, The White House, Saint Mark's Basilica in Venice--the commentary reflects back on the artist and the billions of people he may see himself representing, who when standing isolated and invisible have no more than this impotent gesture to comfort us. (There is more on Ai Weiwei under 2007 and 2010-2011.)

2005: In the late 1960s, when I was coming near to graduating from grammar school, I had to hear of The Trail of Tears from the Native American folk singer and political activist Buffy Saint-Marie. Her authorship and impassioned singing of My Country Tis Of Thy People Are Dying, on one of the televised variety shows for the new youth audience, was nothing short of a bomb going off in my parents' living room. Decades after the close of the 1960s, the history of the Trail of Tears that saw the forced relocation and genocidal treatment of the Cherokee People, is now taught as the most infamous implement of the Indian Removal Act of 1830. While being made to walk upwards of 2,200 miles (now the territory of nine states) without sufficient protection from below-freezing temperatures, the tribe was issued blankets from the US Army knowingly infested with small pox. Estimates have it that between starvation, freezing and disease, 1 of every 3 to 4 Cherokees died on the trail.

In 2005, things had advanced to the point where a Native American artist can receive a grant to install a permanent art monument, and one that is bitingly ironic, to the Cherokee dead. At least so long as the artist is possessed of the international stature of Hachivi Edgar Heap of Birds, and the sponsorship comes in the form of an institution of higher learning such as the Georgia College and State University at Milledeville, Georgia, which underwrote the 2005 installation of Do You Choose to Walk Trail of Tears. It is the case that the signage of this work, as well as much of the signage for which Heap of Birds is famous, has its inconspicuous and ironic qualities to help sell it to the administrators of institutions and charitable foundations. And painted on the same metal and with the same shape and colors of city street signs given to announcing parking regulations, they blend into the landscape of mundane signage. Many Native Americans would like to see more explicit and pointed indictments. Yet, at those moments we come upon the signed question posed without a question mark, "were you forced to walk," even the historically uninformed (and perhaps the uninformed in particular) are more given to being stirred by the mysterious inquiry, enough to pay attention to the accompanying signs that we then find encircling a bronze sculptural figure of a man slumped over from exhaustion.

Heap of Birds is himself quick to point out that, as a member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho nation, he is not representative of all Native Americans, nor should he be. In one newspaper interview he has stated, "I really try to explain that I don't speak for all Indians. There isn't really a Native America--only a series of many, many tribes and languages and religions."

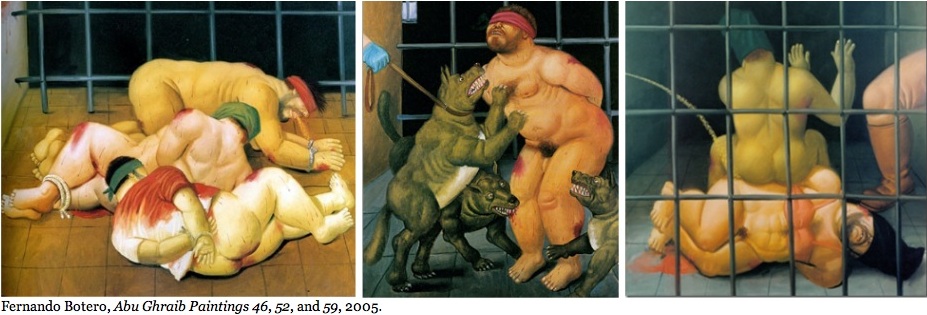

2005: The renowned Colombian artist Fernando Botero unveiled a series of over 80 paintings and drawings which depicted his typically stylized renditions of the body, though this time they were the bodies of prisoners being abused by American guards at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. The men are seen being hit by guards, attacked by dogs, made to climb over one another nude in human pyramids, and humiliated by being made to wear women's underwear. Although none of the paintings summoned to mind any specific photograph released by the press, all the paintings could be immediately contextualized by anyone who had seen them. Botero has always elicited mixed response from critics and viewers for his purposively obese and at times grotesque figures. But astonishingly, at least to this nonfan of Botero, the paintings are all both riveting and summon compassion. I for once was in complete agreement with Arthur Danto that the "Botero Abu Ghraib, are masterpieces of what I have called disturbatory art--art whose point and purpose is to make vivid and objective our most frightening subjective thoughts."

Botero achieves this by explicitly referring back to painting's legacy in Roman Catholicism and it's fixation on the body of the scourged and mangled Christ figure. We don't have to see in the paintings or the photographs that they derive from the pathos that is peculiarly Catholic or even Christian to wonder how a civilization that for so long worshipped a God with ritualized re-enactments and art underscoring the inhumanity of man as an evil to be expunged, could produce such wanton pleasure in the torture and humiliation of other human beings. The value in remembering this religious legacy of painting even for the secularist is that such a memory reminds us that faith is often dismissed with the conceit that we believe we advanced from such superstitions and the barbarism that kept them alive. Botero's evocation of the religious paintings of Europe's past in conjunction with the photographs of Abu Ghraib suggest that perhaps we haven't advanced so far from the barbarism that required the justice of a deity after all. Socialism and its political actions, we may recall, grew out of the compassionate teachings of religions, as the Latin American liberation theologists constantly remind us.

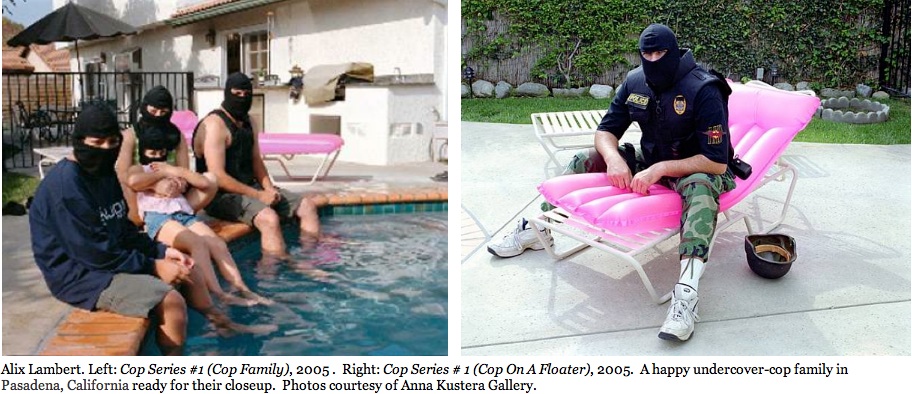

2005: After ABC's Nightline devoted a program to the documentary, The Mark of Cain (2000), that artist Alix Lambert had made about the prison tattoos of Russian inmates, Lambert received a call from the FBI inviting her to screen the film at a law-enforcement convention about Russian organized crime. At the convention she met many detectives and undercover cops whom she became interested in photographing. The world of law enforcement seemed to her an obvious flip side to the world of criminals. Only one agreed to let her photograph him and his family at home--on the condition that they could mask their faces.

2005: Chim↑Pom, the collective of Japanese artist activists may be unique in the world for staging guerilla art tactics in public that occupy the sky as well as the ground. In I'm Boken, 2005, Chim↑Pom joined the minefield clearers of Cambodia, dropping modern household appliances on the newly discovered mines and filmed the explosions from the air. At home in Tokyo, the group in 2007 enacted Black of Death by driving around the city's public centers and government buildings both on motorcycle and by car to roust out and lead the city's formidable crow population through the skies by hoisting a stuffed crow into the air to the sounds of a megaphoned cacophony of recorded crow calls. Also in 2007, in a work called Pika, ピカッ, a word that has become the onomatopoeia for the flash of an atomic bomb going off in Japanese manga, was sky written above the Hiroshima Peace Memorial at the beginning of the morning rush hour. The public outcry against the work compelled Chim↑Pom to publicly apologize to the victims of the 1945 Hiroshima Bomb. (There is more on Chim↑Pom in 2011.)

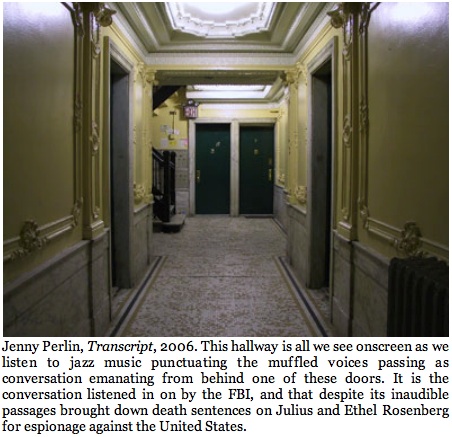

2006: What I remember most about the screening of Jenny Perlin's video, Transcript, is besides being treated to the kind of semiotic close reading that was often induced by minimalist and structuralist films made after the influence of Godard's work in the late 1960s and early 1970s, are the effects of being made to study a single image at a prolonged period, which impresses more acutely on the mind the lacuna in the conversation that accompanies the image. The heightened level of concentration that can be attained under such circumstances makes us conscious that the poor quality of the sound and the jazz music playing in the background made it impossible to ascertain a continuous conversation for the better part of the duration. For the simple pleasure of being able to follow the actors through the artwork without the pressure of having to file a report on the contents of the conversation, I filled in the blanks of the perceived conversations with cordialities that matched the music and tones of the voices despite my awareness that I was listening to a reconstruction of a recording made of four people convicted of being spies for a foreign government.

At the end of the screening, when I then read a copy of the actual transcript of the recording submitted to the court as evidence of the Rosenbergs' treason, I felt a shock course through me. The voids that I had filled with pleasantries, the FBI transcribers had filled with treasonous statements. The obvious absurdity and arbitrary malice of the transcribers became so overwhelming, it seemed impossible to remain objective despite having come to the screening with the intention not to judge the guilt or innocence of the Rosenbergs. The most I could do is question what other evidence against the couple was substantive and decisive in a way the transcript is not.

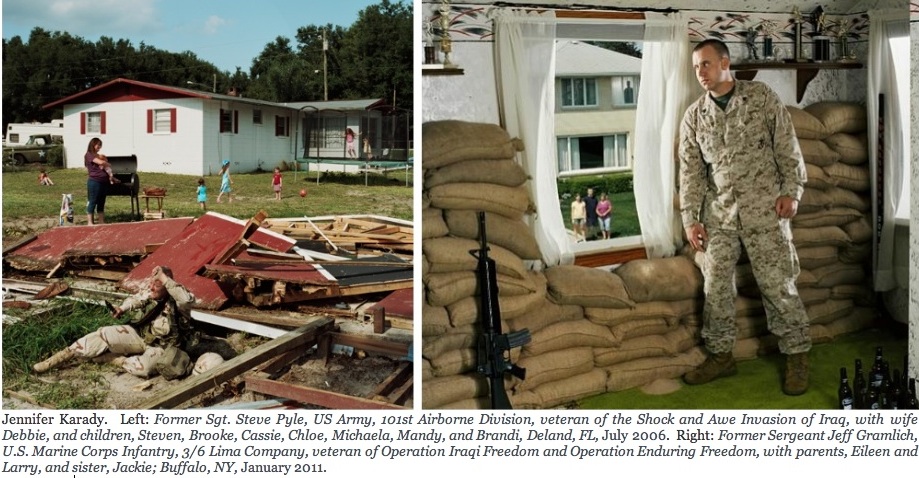

To hear of Jennifer Karady's comic renditions of PTSD-afflicted ex-servicemen and women revisiting their most devastating moments in combat seems an outrageous and tasteless stunt. That is until we actually see the anecdotal scenes that Karady crafts with real ex-service men and women and their reunited families from numerous cities across the U.S. The humor of black satire emanates, but so does the self-effacement of the soldiers who know that a sense of humor is what keeps them from becoming the basket cases they portray.

2007: Whoever hadn't yet heard of Ai Weiwei in the art world by the time of Documenta 12 in 2007, knew of him thereon. Ai became renowned for raising and spending 3.1 million Euro to bring 1,001 Chinese people from all walks of life--farmers, merchants, business people, students, entertainers, medical professionals--to the town of Kassal to participate in his work, Fairytale, for the duration of the art gathering. Inspired by Kassal being the nucleus of so many of the fairytales written by the Brothers Grimm, Ai claims that he initially wanted to bring so many Chinese people as an audience, but then understood the gesture as an artwork in itself. At the time, ChinaDaily.com reported that Ai believed that "the basic concept behind the work is to create a condition which encourages self experience and extends people's participation of art." As for his participants, "I told them they needn't do anything. I just want them to go to Kassel, be happy, relax, see the show, and come back safely." Ai arranged for his 1,001 to lodge in a two-level dormitory house that was converted from a Volkswagen factory, with the men and women each occupying one level. During their stay the participants were free to go wherever they wished. For many of the 1,001, the freedom from want and regulation was indeed a fairytale, with Ai their fairy godmother.

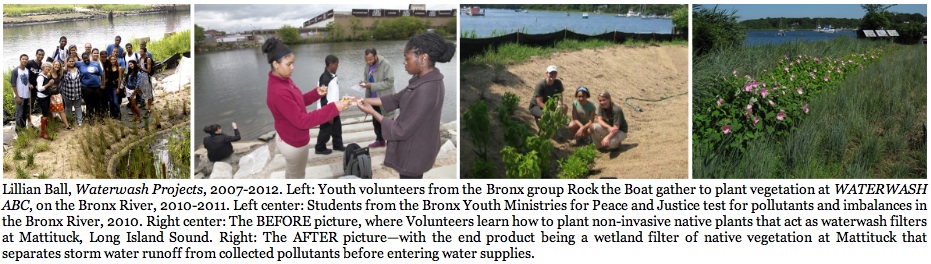

2007-2012: Lillian Ball doesn't distinguish between art and civic responsibility as she builds up sustainable wetlands that double as filters preventing polluted storm water runoff from entering the natural water supply. Her art includes organizing youth volunteers to learn and contribute to the perpetuation of the ecosystem. It involves teaching and applying water testing methods to record the progress of the natural water filtration. Then there is the planting of non-invasive native plants as waterwash filters, which she has so far overseen on the Bronx River and at Mattituck, Long Island Sound. The end product is a wetland filter of native vegetation that separates storm water runoff from collected pollutants before entering water supplies, while also redefining the human contribution to a sustainable ecosystem as art.

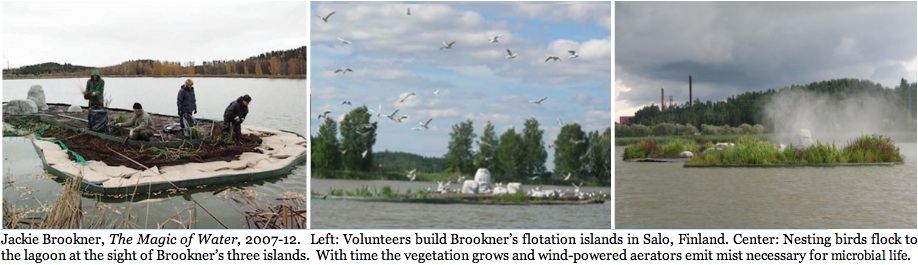

2007: In Salo, Finland, Jackie Brookner organized local volunteers, regional science experts, and students to adapt lagoons, formerly used in sewage treatment, to the needs of migrating birds who must protect their eggs from onshore predators. Volunteers built three of Brookner's floatation islands that immediately attracted nesting birds with lightweight "rock formations" for protection of eggs and indigenous plants for phytoremediation. Mist emissions from wind-powered aerators beneath the islands stimulate microbial life which feed the food chain that in turn feed the birds.

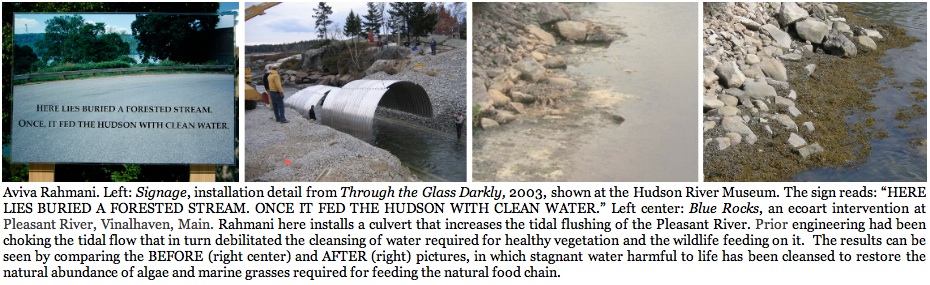

2007: Technology, science and art almost know no distinctions in Aviva Rahmani's value system. The installation of a culvert is as much a choice of medium as it is a crucial part of Rahmani's project to restore 26 acres of wetland at Pleasant River, Vinalhaven, Maine. The estuary had become susceptible to stagnation because it is so dependent on adequate tidal flushing. But in recent years the flushing had been reduced because of an Army Corps of Engineers narrow that Rahmani found to be choking the wildlife artery. The results of the increased flow afforded by Rahmani's culvert can be seen in the before and after shots (above) of the river bank. In the before photo we see virtually no algae or marine grasses to sustain wildlife, whereas in the after photo there is an abundance of algae and other bacteria-rich vegetation restored. As Rahmani explains, "small crustaceans or worms at the bottom of the food chain feed on healthy bacteria that in turn feed on detritus (detritivores). These animals may attach or hide themselves in the vegetation and then be eaten by small fish, such as mummychogs, or silversides, which may then be eaten by ospreys and eagles."

2008: In December, Adelina Von Fürstenberg's feature-length film, Stories on Human Rights was screened at The Palais de Chaillot, Trocadero, in Paris to commemorate the 60th anniversary of The Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The film is actually a collection of short films shown in their entirety, and made by 22 video artists and filmmakers from around the world. They include, Marina Abramovic (Serbia/The Netherlands), Hany Abu-Assad (Palestine), Armagan Ballantyne (New Zeland), Sergei Bodrov (Russia), Charles De Meaux (France), Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster & Ange Leccia (France), Runa Islam (Uk/Bangladesh), Francesco Jodice (Italy), Etgar Keret E Shira Geffen (Israel), Zhangke Jia (China), Murali Nair (India), Idrissa Ouedraogo (Burkina Faso), Pipilotti Rist (Switzerland), Daniela Thomas (Brazil), Saman Salour (Iran), Sarkis (France/Turkey), Bram Schouw (The Netherlands), Teresa Serrano (Mexico), Abderrahmane Sissako (Mauritania), Pablo Trapero (Argentina), Apichatpong Weerasethakul (Thailand), and Jasmila Zbanic (Bosnia). Since then the film has been screened in more than 70 film festivals around the world.

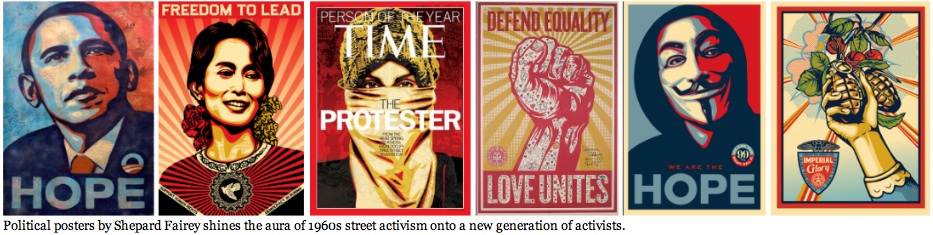

2008-2011: Street artist Shepard Fairey single-handedly revived the graphic art of the American political poster for a new generation of activists. Although a master of the offset print throughout the decade, his renown in the mainstream began with his Obama HOPE poster, 2008. That same year he made his FREEDOM TO LEAD poster, depicting the former Burma political prisoner, now politician, Auug San Suu. After that came OCCUPY PROTESTER, 2011; the poster to benefit Marriage Equality, LOVE UNITES, 2011; the Occupy poster, MR. PRESIDENT, WE HOPE YOU'RE ON OUR SIDE, 2011; and IMPERIAL GLORY, 2011, which takes up President Eisenhower's warning perennially bewaring Americans of the Military-Industrial Complex.

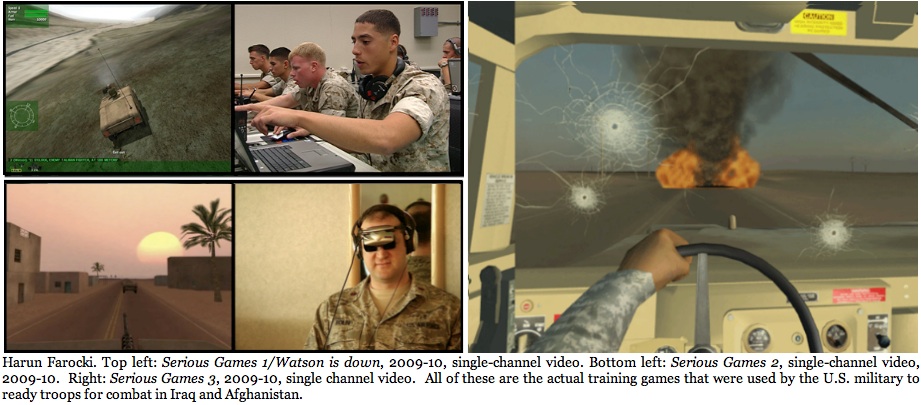

2008: Harun Farocki's four-part project Serious Games (2009-10) uses photorealistic computer-generated imagery in processes in training military personnel in the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. We watch documentation of soldiers being trained before missions with demonstrative games that map out enemy terrain and simulate climate conditions. Some of the interactive programs filmed are designed to help ex-servicemen alleviate Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) by virtually reliving the devastating events leading to their disorders--at times the death of a fellow soldier and buddy. Distinguishing between real photography and simulations in such emotionally charged reconstructions can be therapeutic at the same time that it can confuse reality with a videogame.

The rationalization, as Farocki sees it, is that, "War appears to have ceased being a hard, irrational, unpredictable material reality and becomes a science that could be modeled, predicted and controlled." Besides that such control is no more than a conceit, what is most questionable about simulation training is how dehumanized war becomes through repeated exercises that can conflate the simulation with the real experience of war to the extent that human beings are only experienced as enemies or comrades, with one set of expectations reinforced for each--and not necessarily the best for establishing the peace desired in the larger effort.

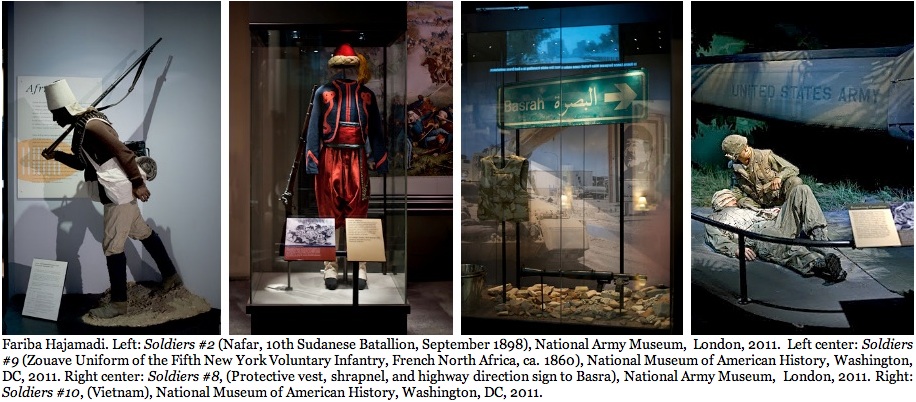

2011: Fariba Hajamadi's photographs, though appearing to be straightforward documents of museum exhibits, take on the double readings of self-referential queries. The questions being asked regard the assumptions that institutions pass off as objective facts and cultural codes when they really often perpetuate historically- and textually-relayed fictions and myths. In short, a Hajamadi photograph of a museum exhibit provides us the opportunity of a prolonged close reading of the exhibit's cultural and political assumptions, combined with some background provided by the artist that enlarge the disparities between the imagined culture and the real one.

Since the 1980s, art and ethnological museums have in the last three decades shed many of their colonial-era political and social assumptions. But Hajamadi has found that war museums in particular hold onto a marked bias in the valuation of differences between cultures and nations that had engaged in war. In the dioramas of The National War Museum in London and the National Museum of History in Washington, DC, that are represented here, Hajamadi reflects on the institutionalized resistance to postcolonial self-reflection that imbues the displays with persistent stereotyping, monolithic assumptions, presumed "otherness" at the expense of our sameness, and an erroneous equation of difference with polarity and opposition. It makes sense that the war museum would perpetuate such historical misreadings--the kind that would privilege the host nation at the expense of the represented nation especially when the host nation is a perceived winner of a war. Yet even when the host nation has withdrawn with questionable or no gains in a war, face-saving accounts of history fraught with factual misrepresentations, generalizations, and overall misunderstandings of the differences between the two sides mark the display labels and placards. Often the displays neglect the people whose country has been occupied if not rendered them entirely invisible to the display, such as the Basra and Vietnam displays here depicted.

2010-2011: Crackdowns on Middle Eastern Artists

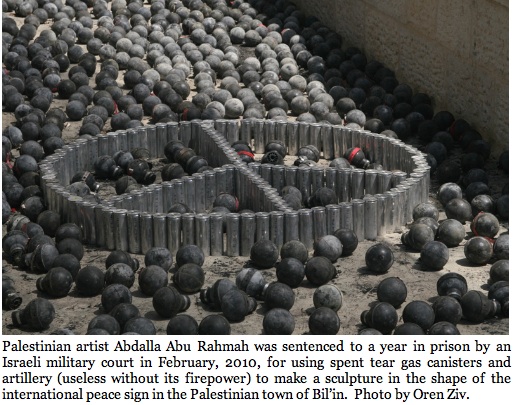

February, 2010: Palestinian conceptual sculptor Abdalla Abu Rahmah was sentenced to a year in prison by an Israeli military court for "arms possession," the "arms" in question being the spent gas canisters and projectiles shot at Arab demonstrators by the Israeli Army in the town of Bil'in. Rahmah collected the spent artillery (useless without the firepower needed to fire them and the gas to fill them) to construct an outdoor sculpture in the shape of the international peace sign. More likely, Rahmah is of interest to the court for being a coordinator of the Bil'in Popular Committee Against the Wall and Settlements.

April 4, 2010: Juliano Mer-Khamis, an actor, filmmaker, and the founder and director of The Jenin Freedom Theater is shot five times and killed in Jenin by Palestinian terrorists. No suspects were apprehended, but he was marked as an enemy by both Israelis settlers and Palestinian hardliners for both his artistic productions and his activism made in the name of the Palestinian peace movement.

December 20, 2010, Iranian film director Jafar Panahi was accorded a six-year jail sentence in addition to being forbidden from leaving the country and banned for twenty years from producing and directing films, writing screenplays, and giving interviews with either Iranian or foreign media.

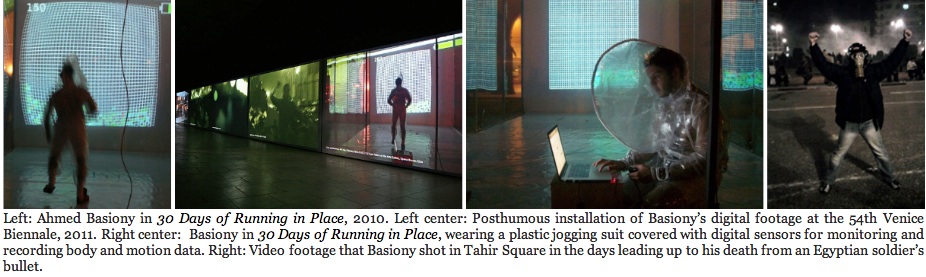

January 28, 2011: Egyptian New Media artist, Ahmed Basiony, was shot dead as he filmed video footage of the pro-democracy protests and occupation of Tahir Square. Basiony had earlier been picked to represent Egypt at the Venice Biennale. Basiony's friend, Shady El Noshokat, and Egyptian Pavilion curator Aida Eltorie selected and projected documentary video of 30 Days of Running in Place, an installation and performance that Basiony had undertaken in 2010 at the Palace of the Arts Gallery in Cairo, Egypt, alongside footage Basiony had shot in Tahir Square in the days prior to his death.

January 2011: Exactly seventeen months after Ai Weiwei was beaten by Chinese police for refusing to cease his investigation into poorly constructed school-buildings that had collapsed and killed over 5,000 school-children, the government demolished Ai's studio for the alleged reason that it was illegally built. In the ensuing months, relations between Ai and officials exacerbated to the point that on April 3rd, Ai was detained and arrested at Beijing airport, his new studio cordoned and searched, his laptops and computer hard drives confiscated, and his wife and eight staff members detained in what is reported by officials as an investigation of the artist's alleged financial crimes. In the interim, Ai's accountant, driver, and studio partner all disappeared, in what is rumored to be an official example that no Chinese dissident, regardless of his or her international esteem, is untouchable by the state. It later was confirmed that the government had wrongly suspected that Ai was a source for the spreading 2011 pro-democracy movement known as the "Jasmine Revolution," inspired by the democracy movement in Tunisia and the spreading Arab Spring.

2011: In the above photos, and their video Real Times (2011), the Japanese art collective Chim↑Pom employ what is their most personally dangerous guerilla art tactic. Members of the collective donned hazmat suits to photograph their walk to the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear-power plant only weeks after the disaster. This is the plant that suffered massive equipment failures and reactor melt downs as a result of the 2011 earthquake and tsunami that damaged a reactor's cooling system, producing the largest nuclear disaster since Chernobyl in 1986. In the center photo, a terrified Toshinori Mizuno works "undercover" to avoid arrest as he is photographed holding up a referee's red card (the sign that a game player is to be penalized) in front of the melted third Dai-ichi reactor. Chim↑Pom then stake claim to the Dai-ichi nuclear-power plant by waving their hand-painted flag of conquest--a Japanese national flag morphed into the icon of the international radiation symbol.

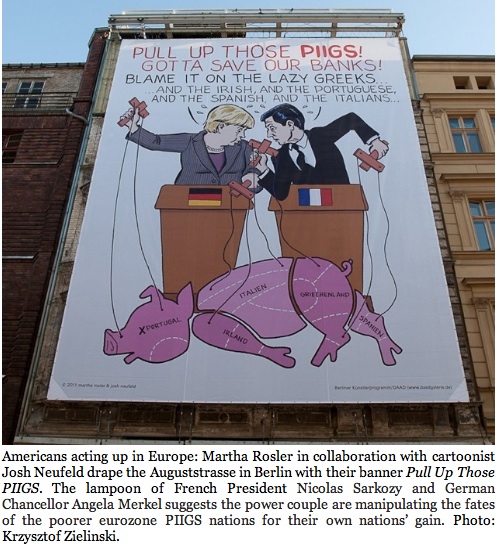

2011: In October, Martha Rosler in collaboration with cartoonist Josh Neufeld installed a banner in October 2011 at the Auguststrasse, the street in Berlin that is a virtual mall of art galleries. Caricaturing French President Nicolas Sarkozy and German Chancellor Angela Merkel pulling the strings on a puppet pig, a play on PIIGS, the acronym for the five eurozone nations, Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece and Spain. Anything but displaying the subtlety or irony of the more nuanced artists, Hans Haacke or Jenny Holzer, the banner is a Left-journal cartoon scathingly commenting on the austerity measures that will shrink the PIIGS economies while the pair espouse the Spartan rhetoric that austerity will strengthen and ultimately expand them.

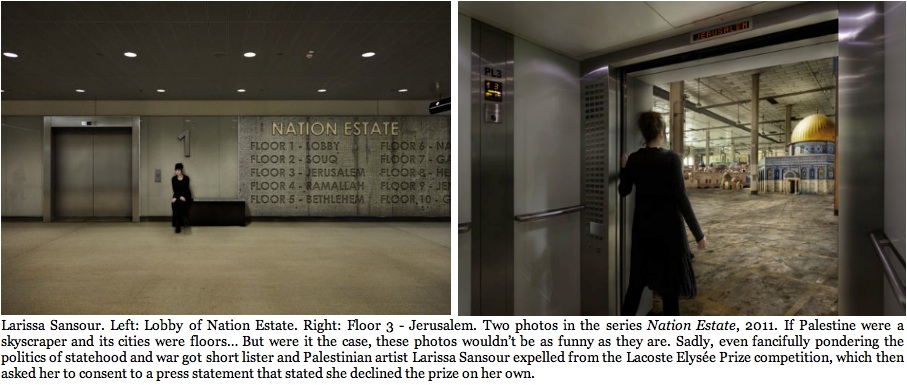

2011: In late December, the Lacoste Elysée Prize for photography, which awards its winner 25,000 euros, was shut down when it was disclosed to the press that the French clothier had demanded that Palestinian photographer and video artist Larissa Sansour be disqualified for her submission of Nation Estate, 2011, a three-photograph series deemed to be "pro-Palestinian." In an interview with the magazine ArtAsiaPacific, Sansour stated, "In addition to being eliminated from the competition, I was also asked to approve a statement saying that I had withdrawn voluntarily 'in order to pursue other opportunities.'"

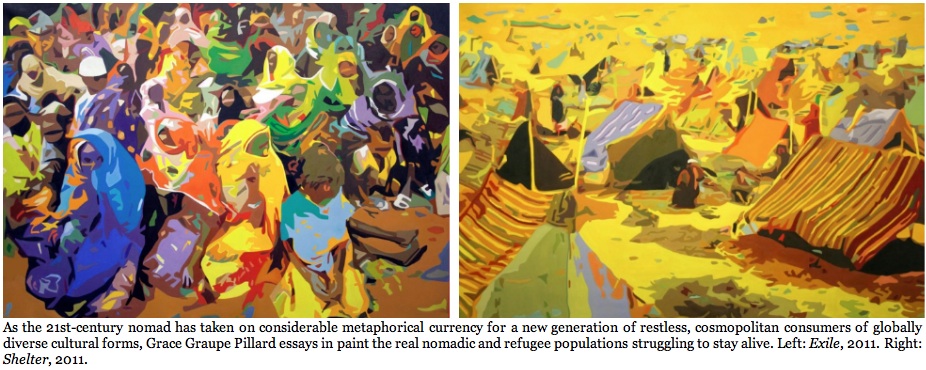

Finally, Grace Graupe Pillard's painting of refugee camps remind us that we have excellent reason to hesitate in our embrace of nomadism as the chief metaphor to denote the contemporary artist's and critic's movement among diverse cultural and ideological models when nomadic societies are today nearly subsumed into sedentary cultures. For that matter, the technological observation and regulation of immigration around the world is more stringent today than it has ever been. There may be greater freedom of travel among affluent and middle class world citizenry, but even as we cheered the razing of the Berlin Wall, invisible, ideological and bureaucratic walls were being erected to restrain impoverished populations. Eastern Europeans, who first flooded the West after draconian Soviet bloc regulations on emigration were lifted, have since had their migrations slowed to a trickle by the immigration laws of Western powers. The U.S. went on to block the entry of Haitians, Mexicans, and Chinese who use desperate means to egress their homelands. Fifteen years after the Berlin wall was razed, a wall went up between Israel and the Palestinian territories preventing Arabs entry into Israel, just as Israelis are still forbidden in various Islamic nations. In this respect, despite their brilliant coloring, Pillard's paintings remind us that the few populations today migrating in large numbers--Somalians, Sudanese, Kurds, Croats, Serbs, and Bosnian Muslims―aren't nomads, but forcibly resettled refugees.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.