North Korea successfully tested its first intercontinental ballistic missile, or ICBM, this week ― a feat U.S. President Donald Trump had dismissed as an impossibility shortly before his inauguration in January.

The ICBM, potentially capable of carrying a nuclear bomb to Alaska, has triggered fierce condemnation and stoked renewed fears over North Korea’s nuclear aspirations and abilities. Trump vowed to confront Pyongyang “very strongly” on Thursday.

At an emergency United Nations Security Council meeting held on Wednesday to address the recent launch, U.S. Ambassador to the U.N. Nikki Haley said Washington was still considering its options, including the use of military force against the hermit nation.

North Korea has spent years working to develop its highly secretive weapons program, with the goal of creating a nuclear-tipped missile capable of reaching the continental U.S. Experts can only estimate just how long this might take, but they agree that Tuesday’s ICBM launch is sounding an alarm over a threat that has been a long time coming.

This shouldn’t be surprising.

“The test on Tuesday was just a single data point that is kind of being used now as bell for waking people up on an issue that’s been developing for quite some time,” Michael Elleman, senior fellow for missile defense at the International Institute for Strategic Studies, told HuffPost.

“If you look at the pattern North Korea has demonstrated for the past three years, they are very actively trying to develop new strategic capabilities, or nuclear weapons. This itself is what is worrying,” he said.

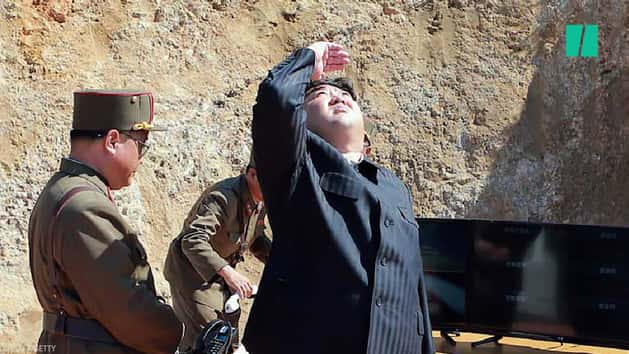

North Korean leader Kim Jong Un warned early this year that his regime was preparing to test a long-range missile, prompting Trump to swiftly dismiss the threat.

And after news of a North Korean ballistic missile launch broke in April, U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson responded by saying, “North Korea launched yet another intermediate range ballistic missile. The United States has spoken enough about North Korea. We have no further comment.”

The official U.S. reaction to this week’s test has been starkly different. Tillerson described the ICBM as “a new escalation of the threat to the United States, our allies and partners, the region, and the world.”

But the launch should come as no surprise, according to experts who think a nuclear ICBM is in the works.

“This is a threat that’s been gradually developing for many years now, and it’s been well-documented,” said Joel Wit, senior fellow at the U.S.-Korea Institute at Johns Hopkins University and the founder of the affiliated website 38 North, for which Elleman is also an analyst.

“The problem is, a lot of people weren’t taking it seriously, and North Koreans continue to move forward,” Wit told HuffPost, “and now we’re at the point where we are.”

While the ICBM launch itself wasn’t unexpected, it did offer some surprise, according to aerospace engineer and North Korea analyst John Schilling.

“It wasn’t surprising that North Korea attempted an ICBM test; we expected that to happen sometime this year or next year at latest. What’s surprising is how successful it was. North Korean missile tests ― in particular, complex, long-range missiles ― almost never work the first time,” Schilling said Thursday at a 38 North press conference.

“This missile probably can reach Hawaii, probably not the continental United States, but we expect they’ll be working to improve the range,” he explained.

Schilling said it could take a couple years to develop the missile’s technology to reach the U.S. mainland, and added that “there’s almost no possibility of this missile reaching the U.S. East Coast.”

There could be a lot of tests in the next few years.

Understanding when North Korea might develop and test a nuclear ICBM depends on a number of complex factors ― including the size of the attached nuclear device and the location of the target ― that can’t be confirmed.

According to Schilling, Pyongyang can probably fit a nuclear warhead on an ICBM “pretty much immediately,” but he noted that the North Korean government will likely spend a few weeks or months deciphering the results of Monday’s test before working to arm the missile.

Elleman, noting that he “can’t envision a scenario where North Korea would actually try to use nuclear weapons, except if the regime was directly threatened,” explained that such a missile could be developed within three years.

“They could test something capable of [reaching the continental U.S.] anytime in the next six to 12 months ― you know, do an initial test. It may succeed, it may not succeed,” he said.

“From a strictly deterrent standpoint, it doesn’t have to be certain to work. Just a possibility that it works is going to change the U.S. political calculus.”

- North Korea analyst John Schilling

North Korea likely doesn’t have the same standards of reliability as countries like the U.S., Russia, or China, Elleman said, meaning it wouldn’t conduct nearly as many tests under different operating conditions and environments to ensure success.

“We don’t know what their criteria will be, but say they want it to be reliable enough so that they have high confidence that more of the missiles will succeed than fail,” he explained. “Then they’re going to have to do a dozen tests over two or three years, of a specific system, assuming all goes well. A lot of things can go wrong to stretch that schedule out, but for planning purposes, that’s what one is looking at.”

“But that puts them in a very precarious position of being in a situation where they feel they need to use the weapon, they push the button and nothing happens,” noted Elleman. “They’re assuming a lot of risk by prematurely deploying or deploying without sufficient testing.”

But as Schilling points out, “from a strictly deterrent standpoint, it doesn’t have to be certain to work. Just a possibility that it works is going to change the U.S. political calculus.”

“Even now, an unreliable system capable of limited operations against targets in the United States changes the diplomatic aspect of North Korean and South Korean political affairs substantially. It does give [North Korea] a direct deterrent against United States attacks,” he said Thursday.

“If North Korea was to launch this missile under combat conditions tomorrow, with 15 minutes of warning and maybe American or South Korean missiles already en route, it would not succeed,” Schilling predicted. “But, given a few more tests and another year or so to train their launch crews, the system is going to become substantially more reliable.”

The U.S. will need allies.

As tensions escalate, Trump has placed increasing pressure on China, North Korea’s major trading partner, to exert its influence over the isolated state.

“If China is not going to solve North Korea, we will,” Trump told the Financial Times in April. “That is all that I am telling you.”

Later that month, after meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping to discuss Beijing’s relationship with Pyongyang, Trump expressed a more moderate view of China’s influence: “I felt pretty strongly that [China] had a tremendous power over North Korea. But it’s not what you would think.”

But Trump’s frustration with China returned after this week’s ICBM test. On Monday, he tweeted: “Perhaps China will put a heavy move on North Korea and end this nonsense once and for all!” Then, on Wednesday, he added: “So much for China working with us - but we had to give it a try!”

Elleman says he fails to see how these attacks on China are helpful in reining in the North.

“We need China’s cooperation, and publicly shaming them is not going to change their national interests,” he said. “[China’s] primary interest is a stable North Korea. What we need is sustained and determined discussions with China and Russia on this issue, and to try to develop a consensus plan on moving forward to reduce the tensions and possibly freeze the North Korean nuclear missile projects.”

“We need China’s cooperation, and publicly shaming them is not going to change their national interests.”

- Michael Elleman, International Institute for Strategic Studies

Elleman also expressed concern over Trump’s repeated vows to take unilateral action on North Korea, if necessary.

“We can’t just do this on our own. We also have to do it in concert with our allies in the region, most notably South Korea and Japan,” he said. “The ones that will suffer the most consequences are our allies. This is where Trump worries me a little bit with his ‘America first’ positions. Does he fully appreciate what’s required of the United States to maintain peace and security now, and in the long-term future? He makes me nervous.”

Pyongyang’s progress toward creating weapons that can reach the U.S. raises questions about Washington’s ability to defend its allies in the region, Wit said.

“Part of that defense system is what’s called extended deterrence ― our willingness to use nuclear weapons in the defense of our allies, if it came to that,” he explained. “Because the North Koreans might be able to respond and attack the United States with nuclear weapons, that increases doubts that we would actually follow through on our threats.”

How concerned should I be?

While the full extent of the North Korean regime’s nuclear capabilities is largely unknown at this time, experts agree there is reason for concern.

“Whether they can strike the U.S. or not, the nuclear capability is destabilizing to the region. Added on top of that is this emerging capacity to be able to actually target cities of the United States with a nuclear weapon. This is disturbing because I think it’s going to embolden the regime,” said Elleman. “Also, there’s always the possibility of an accidental launch, or accidentally escalating into an open conflict with the North Koreans. This is just an added dimension to the existing worry.”

However, he added, “I wouldn’t feel uncomfortable, I think there are many more realistic threats to be concerned with, it’s just that if North Korea were to use nuclear weapons, whether it’s against the U.S. or whomever, the consequences are devastating.”

Wit suggested that on a scale of 1 to 10, the level of concern has likely reached a 7 or 8. Because the ICBM launched this week is capable of reaching Alaska, “It’s obviously more of a threat than the other missiles that cannot reach the United States ― so that’s the point, it’s a direct threat,” he said.

Elleman maintains that “for the average American, this isn’t a top concern” at the moment, but speaking “quite frankly,” he added: “My largest concern is that we mistakenly find ourselves at war with North Korea ― a war in which a nuclear weapon could be used by North Korea. We have to be bold, but cautious at the same time, when formulating North Korean policy.”