There's a world

where I can go

and tell my secrets to

In my room

In my room...

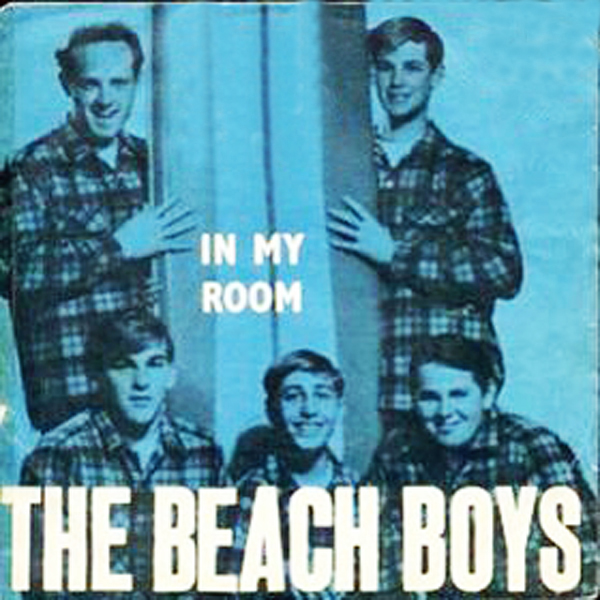

The haunting Beach Boys classic springs to mind because that's where I find myself as I'm writing this: in my childhood bedroom.

The same room, in fact, where I first heard that song. The aching harmonies of "In My Room" give voice to a longing shared by every American teenager: the need for a safe space, four walls to call your own.  A place where you can shut out the world and be alone with your private thoughts. And dreams. And hormones. It helps to have a reliable lock.

A place where you can shut out the world and be alone with your private thoughts. And dreams. And hormones. It helps to have a reliable lock.

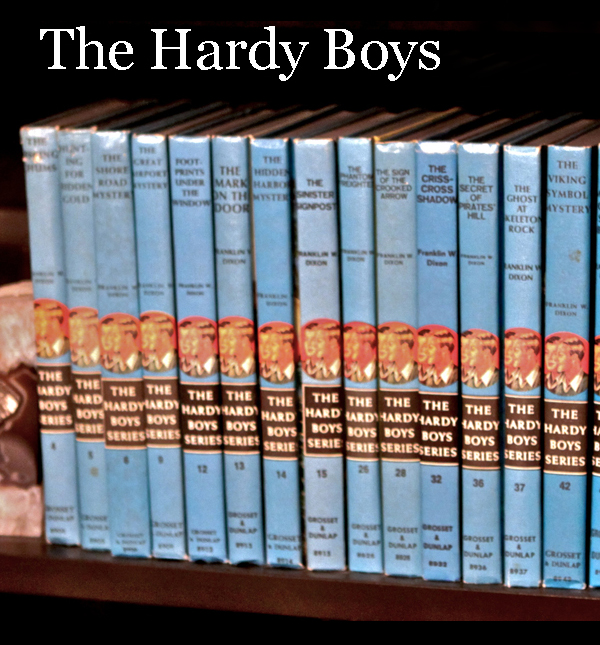

Very little has changed up here over the years. Coming back is like sneaking into the past and inhaling my childhood. Same built-in desks, same bumpy ceiling tiles, same odd little troll dolls standing guard, their frozen smiles and eerie, unblinking stares making them dead ringers for the Olsen twins on Full House. The Hardy Boys Mysteries line the same shelf they always have, bookended by the purple foot I sculpted in Betty Fryga's Tuesday afternoon art class. The foot no one understood.

My older brother and I first moved up here around the time Batman hit the airwaves. I was in fourth grade; he was in sixth. The birth of my youngest brother had forced our parents to make some new sleeping arrangements. As a consolation prize for giving up our downstairs rooms, they converted the unfinished attic into what they envisioned as a boy's utopia for Jimmy and me, a sprawling Batcave of our own.

They wisely had the builders install separate sets of his-and-his furnishings: identical desks, bookshelves, closets and dressers, all built-in. Everything matched. Except my brother and me. While Jimmy jumped around in front of his mirror working out his latest Batman moves, I stood posing at mine, perfecting my flawless imitation of Mrs. Thurston Howell III on Gilligan's Island.

The utopia my parents hoped for never happened. Some fish are meant to swim alone. As even a pimply, first-day clerk at Petco can tell you, never put two bettas in the same bowl; they're genetically programmed to kill each other. During the years Jimmy and I shared this space, those bumpy ceiling tiles saw it all: epic battles, final visits from the tooth fairy, dueling puberties and me, lying on the bed, daydream-believing I was Davy Jones in The Monkees.

All these decades later, the only noticeable change in my room is the fact that, instead of two brothers, the beds are now occupied by two dads of the homosexual variety, and their kids. It's spring break for our son and daughter, which, as usual, means Kelly and I have flown them cross-country from California to visit my parents in South Carolina.

To my children this is and always will be Mimi & Pop's House. To me -- regardless of my current address -- it's home, the place I feel safest. Returning is one of my great pleasures in life.

I love my parents for a million different reasons, but mostly, lately, I love them for not dying. I can't help believing that staying put in this house has played a role in that. Meal by meal, task by task, dream by dream, each day they continue building a life together here, an architecture of shared intangibles. To my everlasting gratitude, they've resisted every urge to sell, downsize, retire to the Presbyterian Home or -- that most deafening of death rattles -- buy a condo.

I realize it's selfish of me to be grateful for this. My folks are in their mid-80s; any of those options would make their day-to-day lives easier. But they'd hate it. And so would I. These walls contain the permanent record of my youth.

All I have to do is walk through the back door before random kernels of my past begin popcorning into memories. Before long the memories become stories, stories my kids can't get enough of.

All I have to do is walk through the back door before random kernels of my past begin popcorning into memories. Before long the memories become stories, stories my kids can't get enough of.

It's empowering for kids to hear their parents recount tales of themselves at the same age; it levels the playing field, brings us closer. Through the backward lens of time, we cease being their parents, the powerful to their powerless. Hearing our stories transports them, for a few giddy minutes, from a world of Us versus Them, to nirvana: us as them.

I describe for my daughter Elizabeth how -- at the very desk where she's sketching mermaids -- I slaved for days on my "Louisiana Money Crops" poster. Worth every perfectionist minute, I tell her, recalling how I created vast cotton fields with my mom's makeup puffs. I was the only one in class to earn an A+ from our pruny 4th grade teacher, drawing rare praise for the clever way I chose to illustrate the money crops theme: by gluing bright, shiny nickels on top of the O's of LOuisiana, MOney and CrOps. My daughter laughs as I revel in the glory of it all.

I have her take off her shoes and feel around with her toes until she finds a stiff, chunky spot in the carpet. That, I tell her, is where I spilled a bowl of Elmer's glue mixed with sugar (Louisiana's prime money crop) and I managed to conceal my crime for days by telling my parents I'd redecorated. By hauling our bunk beds to the middle of the room.

This story delights her. But fifth graders are now being armed by their teachers with dubious new weapons like "critical reasoning." Which means Elizabeth has begun to... question some of my stories. Among these is the tale of how her Uncle Jimmy routinely forced me into sadistic re-enactments of what she's been taught to call Cowboys and Indigenous Peoples of the Americas. My son, 6, listens in rapt, thrilled horror, but this time Elizabeth rolls her eyes as I recount how my brother hogtied me to the foot of my bed, gagged me with a washcloth and tried to scalp me with our dad's new set of steak knives. I'm not even done before she's grabbed my iPhone and started searching for Uncle Jimmy's number. She dials, then puts him on speaker to refute my lies.

Of course he can't and doesn't even try. Instead, Uncle Jimmy gleefully leaps in, providing tons of detail -- things done with binoculars, atrocities involving dental floss and toothpaste -- I've spent a lifetime blocking out. I hang up and break for a cocktail.

Jimmy was a lot bigger than me, a fact he routinely used to his advantage. My son understands this sort of thing all too well; he's nearly five years younger than his sister. Which might explain why his favorite story is the one of how I exacted my revenge. I recount how I bided my time until the day Uncle Jimmy returned from the doctor, having been diagnosed with a rare bone condition. I was stunned when they wheeled him in, imprisoned from his chest to his feet in a full body cast. It may have been the happiest day of my life.

In a Zen state of rapture, I floated to our room and began planning how to best seize the moment. It doesn't take long when your prey can't run. My son hangs on my every move as I re-enact my silent, leisurely stroll from the bed to the pencil sharpener, the very same pencil sharpener I used that fateful night. I pause to point out that what I did next was the most cruel act I ever committed as a child, something he is NEVER to replicate no matter how much he thinks his sister might have it coming. Like Jimmy did. "Okay, I won't! I won't! Tell me the story!" blurts James, the suspense nearly causing him to wet his pants. So I do, recounting how my immobilized tormenter, now saucer-eyed with panic, watched helplessly as I slowly selected a teacher-approved, yellow #2 pencil, ground its tip to a fine razor point, and stabbed him in the toe.

Misty watercolor memories of the way we were.

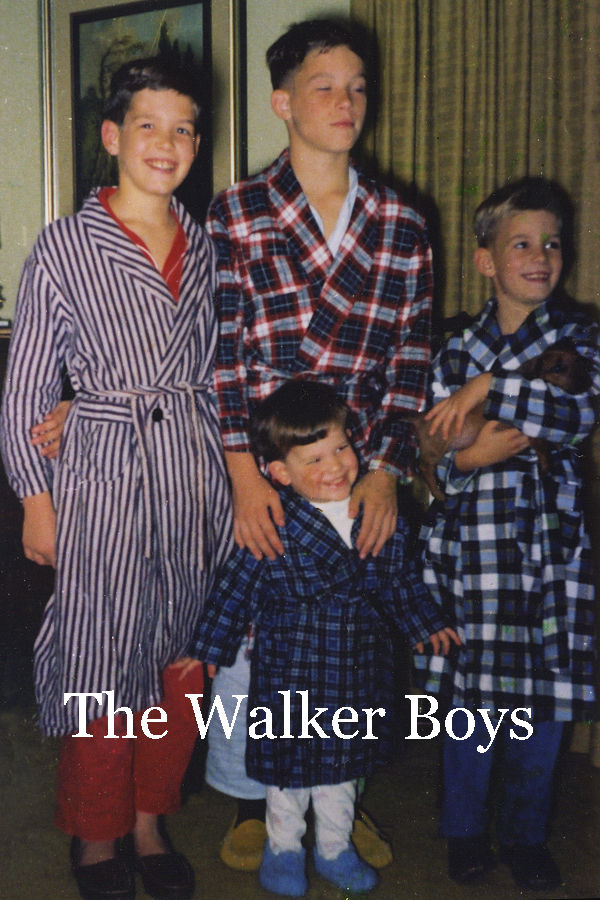

My parents were known locally for their determination to repopulate our town with penises. We were known simply as the Walker Boys -- Jimmy, Bill, George and Andy. To outsiders we appeared harmless. On days like scalping day, or pencil-in-the-toe day, or the day George dumped a cup of warm urine on the rest of us, we could have given riding lessons to the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. How our mother managed to survive without becoming a boozer, or drowning us all in a lake like that women a few counties over, mystifies me. A lot.

I have only one son, and I swear, watching him jolt to life each morning is like witnessing the birth of atomic fusion. When James was two, I had to pry him off the top of the refrigerator where he'd discovered six juice boxes and guzzled every last one. Seating my two-hundred pound self squarely on his flailing, sugar-shocked body, I dialed my mom. "You did this four times?" I shouted, as my Juicy-Juiced changeling pummeled me with an addict's rage. "How the hell are you even still alive?"

She laughed a dismissive, bell-like laugh. It was no big deal, she said. Boys are fun, boys are cute, she loved raising boys. I knew by her answer that one of two things was true. She was either lying or a mutant.

About the time I moved into junior high and my body began to pubertize, a vision of my future began taking shape. It dawned on me that I was meant to be an Artist. I don' t know why; maybe it was the purple foot. I didn't know yet what kind of artist. I hadn't landed on specifics. Poet. Painter. Movie star. Bassoonist. Movie star-bassoonist. I didn't really care. But fame was key.

I thought it might help if I studied a wide variety of artists to see what they all had in common. So I hit the books at our local college library, casting my net wide. I researched every great artist I could think of: Picasso, Horowitz, Marlon Brando, Jimi Hendrix, Shari Lewis. It took weeks before I isolated the single, crucial ingredient they all shared. My heart sank. It was the one thing I lacked in spades: a traumatic, tragedy-laced childhood.

My home life was way too vanilla, which I now knew was a disaster. I immediately set about rectifying the situation. I tried everything, determined to kick-start a little drama in our humdrum family life. Nothing worked. I would launch into violent weeping fits at the dinner table. "Pass the peas." Announce that I had a terminal strain of acne. "Use Clearasil." Fake a grand mal seizure, tumbling down the stairs and foaming at the mouth (frothed-up Colgate). The minty smell blew it.

After a few days, my mom had just about had it. "You want drama?" she finally snapped one afternoon. Opening her desk drawer she pulled out an envelope. "Write me a check and you can have four dramas. And a musical," she said, waving season tickets to the Greenville Little Theatre.

She didn't get it. I was a Walker Boy who wanted to be more: a Beach Boy. A Hardy Boy. Perhaps most of all, Davy Jones in The Monkees.

But nothing was happening at 710 Calvert Avenue to traumatize me sufficiently. You know that aerial footage they show on CNN after a major tornado? Graphic helicopter footage of utter devastation, miles of suburbs flattened in seconds? And there, amid row after row of roofs ripped off like cat-food lids, tree after tree cradling Volvos and washer/dryers, stands that one house, untouched, twiddling its thumbs and whistling in the dark like nothing ever happened? That was our house.

It wasn't as if our town was drama-free. It was a cesspool. At school I'd eavesdrop as other kids whispered their parents' screamed threats of divorce and castration, wondering why they got all the fun. I'd hear a classmate recount the terrifying afternoon she arrived to babysit a neighbor boy, just as his mom's killer was escaping out the back window. And I'd think, "Why didn't the Alberghettis ever ask me to babysit?"

What I didn't know -- was completely clueless about -- was that a full-scale natural disaster was brewing inside my own home at that very moment. A truth so unspeakable, a scandal so damnable, that had the scandal become public, our home would surely have been red-tagged and bulldozed immediately. And it wasn't just happening in our house. It was happening in my room. To me.

As I write this, my son and six plastic Marvel action figures are taking a bath in the same tub I used as a boy. As we were filling it, James asked what action figures I used to play with in my bath. I tell him my first choice would probably have been a Barbie doll, only I didn't have sisters and my parents wouldn't buy me one (dammit). "I would have bought you a Barbie doll," says James, in a voice so sweet it makes me want to hug the soap right off him. Instead, I tell him it didn't matter, because I rarely even got to use my own bathroom once Uncle Jimmy turned 13.

"Why not?" asked James.

"Oh, he kind of hogged the tub," I say. "He'd lock the door and barricade himself in here for hours."

"Which action figures did he like to play with?" asks James.

"Only one," I say, and quickly change the subject.

I'm not ready to tell my 6-year-old the whole truth. If I did, James -- the straightest son of two gay men ever to walk the earth -- would be in there now, sniffing around to see if he could find the Playboys Uncle Jimmy swiped from our neighbor's dad and stashed in the heating duct.

But this incongruous, comical, slightly disturbing image of James clutching his first Playboy does ring a distant bell. As I type these words, I realize I'm lying in the very spot where one fine spring afternoon long, long ago, flipping through that Bible of rock music, Tiger Beat magazine, I had my first epiphany: I don't want to be Davy Jones in The Monkees; I want to touch Davy Jones in The Monkees.

It was the first secret I remember telling this room.

In the movie Tootsie, Jessica Lange, lying on her character's childhood bed, tells Dustin Hoffman, "I made a million plans looking at this wallpaper." We all make those plans -- who we'll marry when we grow up, what we'll accomplish as President. I put mine on hold the day I realized I wanted to touch Davy Jones. And Tom Jones. And Joe Namath. And Bert Convy. And Wayne Adair, the youth minister who ran our teen Bible study.

I confided lots of secrets to lots of rooms after that. There were years of secrets, and deceptions, and lies as I struggled to conceal the natural disaster I imagined myself to be.

Until one boisterous, overcrowded winter night in New York City (where I'd moved, for the excitement). I found myself where I'd told myself I should be, trapped in Times Square, jammed in a mob of thousands, all gathered at the "Crossroads of the World" waiting for the New Year's Eve ball to drop. As I stood there, jostled and freezing, watching five drunks fight over a taxi, I had my second epiphany:

I'm not really cut out for drama.

It seems that when I wasn't looking, my parents inoculated me against it. In the quiet, undramatic home they continue to share, maybe without even knowing, our parents gave my brothers and me what I could finally see is the greatest thing a parent can give a child. Stability. A solid foundation: plain, boring, simple, strong.

When it was time to send me out into the world, somehow my parents sent my room with me.

I don't know how they did it. They may not know themselves. But every day, Kelly and I hope we're doing the same for our children.

The great gift of my life is that it didn't turn out the way I planned. Or feared. Who could have planned what I have now? Who could have known I'd be back in this room two or three times a year, falling asleep to the same distant train whistle, lying next to a man I adore, as our children dream beside us?

I think my room knew. From the beginning.

"In My Room" lyrics by Brian Wilson and Gary Usher

* * * * *

This post is the sixth in a series of Spilled Milk columns by William Lucas Walker that chronicle his adventures in Daddyland.

More Spilled Milk:

Visit the Facebook page: "Spilled Milk" by William Lucas Walker