There's a growing move on college campuses across the country to warn students that novels might threaten their mental health.

Specifically, they might contain "triggers" -- that is, material that might upset students or "cause symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder in victims of rape or in war veterans."

But it's not just survivors of those extreme experiences who are apparently at risk.

At Oberlin College in Ohio, a draft guide was circulated that would have asked professors to put trigger warnings in their syllabuses. The guide said they should flag anything that might "disrupt a student's learning" and "cause trauma," including anything that would suggest the inferiority of anyone who is transgender (a form of discrimination known as cissexism) or who uses a wheelchair (or ableism). "Be aware of racism, classism, sexism, heterosexism, cissexism, ableism, and other issues of privilege and oppression," the guide said. "Realize that all forms of violence are traumatic, and that your students have lives before and outside your classroom, experiences you may not expect or understand." For example, it said, while "Things Fall Apart" by Chinua Achebe -- a novel set in colonial-era Nigeria -- is a "triumph of literature that everyone in the world should read," it could "trigger readers who have experienced racism, colonialism, religious persecution, violence, suicide and more."

That weaselly "and more" is especially murky. It weaponizes all human experience as portrayed in literature; theoretically any book a professor might assign could be "harmful" to somebody, somewhere.

Proponents of trigger warnings for literature seem to think that trauma is incapable of being overcome, healed, or even ameliorated -- as if a traumatic event traps us indefinitely like Jake Gyllenhaal in Source Code. Haven't they ever heard of support groups, therapy, or university counseling centers? They also seem to hold a surprisingly naive view of literature. The trigger alerts being offered presuppose that the words we read are bludgeons and reading about a mugging, for example, is automatically going to make you feel mugged all over again if you were the victim of that kind of crime.

But just because something disturbing is described in a book doesn't mean it will automatically cause us emotional harm. Reading can actually help ease our fears and pain. Reading can be cathartic, even reading about things that have hurt us deeply. Perhaps especially so.

I grew up feeling outcast for many reasons, primarily because my parents were Holocaust survivors and so different from everyone around us that my home felt like an alien planet. They had heavy accents, they were often angry or depressed, they were paranoid about my safety, their past was a closed book. It's no wonder that I grew up feeling secretly estranged from my peers. It wasn't until I read Edith Wharton's dazzling The House of Mirth in college that I began to have access to that sense of difference, that sense of something wrong with me, that profound shame.

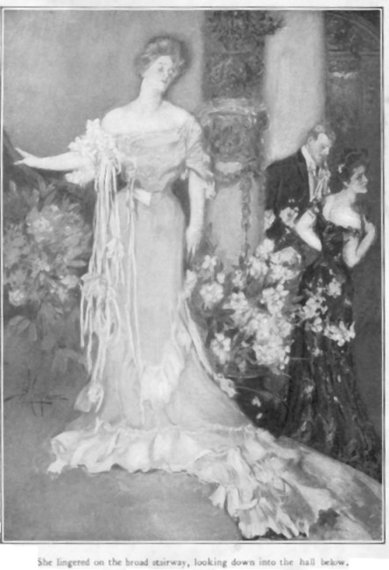

Wharton's fading socialite, Lily Bart, is disgracefully broke in Gilded Age New York where wealth is everything. She needs a rich husband badly, but can never quite manage to ensnare one, despite her rare beauty. Bart's financial exigencies lead her into more and more trouble until at one point in her social decline she's profoundly humiliated in front of a large group of so-called friends in the South of France.

Even writing about that scene years later gives me goose bumps. Though I've re-read the book many times, I still remember my astonished reaction. When I first encountered this stunning scene of exposure and paralysis that dramatizes the shame of a character completely unlike myself, I wasn't traumatized at all. Despite also having been publicly humiliated, and more than once, I felt liberated.

And even though Wharton's portrait of her Jewish character Simon Rosedale in The House of Mirth offended me, what mattered most to me was her grasp of what it felt like to be wounded so profoundly inside. I finished the novel in a fever and read everything of Wharton's I could find, as well as reading about her life. Sure enough, shame was a theme throughout her work.

Even if I couldn't articulate it then, and even though aristocratic Edith Wharton couldn't have been more unlike me, I had found a kindred spirit. I had found fiction that explained me to myself and gave me a way forward, as well as inspiration for my own writing. If someone had warned me that Wharton's novel could be upsetting or painful for whatever reasons, I might have avoided it and missed a book that helped change my life.

Lev Raphael is the author of The Edith Wharton Murders and 24 other books in many genres. You can check out his other books on Amazon here.